Posts

Wiki Contributions

Comments

There's a reasonable argument that we all lose out by calling programmers software engineers, given they lack the training in forensic analysis, risk assessment, safety factors engineering, and identifying failure modes that other engineering disciplines (i.e. civil, mechanical, materials, electrical) have to train in.

A lot of energy in the AI safety conversation goes into philosophizing and trying to reinvent from scratch systems of safety engineering that have been built and refined for centuries around everything from bridges to rockets to industrial processes and nuclear reactors, and we are worse off for it.

This is an excellent subject area with a ton of material -- especially because so many 19th and 20th century social movements were so deeply tied with notions of social, economic, and technological progress, and often sought to use novel technologies to drive revolutionary change. In many cases, solidarity and freedom from hardship were seen as going hand-in-hand with modernity and industrialization.

The most exciting prospect here, imo, is building capacity to identify underresearched and underinvested foundational knowledge areas, filling those gaps, and then building scaffolding between them so they can cross-pollinate. And doing this recursively, so we can accelerate the pace of knowledge production and translation.

Hey there! I'm a startup founder and software engineer who is also one of the folks from the anthropology community who was initially skeptical of Progress Studies, so I can speak to their concerns -- which, to your point, largely came across as snide grumbling amongst academics. Unfortunately, as is often the case with tight-knit communities, their real concerns were understood implicitly and therefore not deemed necessary to communicate openly.

tl;dr, there's a pattern of (some) SV tech types only respecting two areas of knowledge: STEM, and economics (but only some economics -- i.e. not political economy, economic history, labour economics...), and thinking all other areas of knowledge can be dismissed, ignored, and rebuilt from "first principles" by STEM folks.

To a group of people already concerned about this trend who spent their careers studying how different forms of knowledge emerge and are transmitted across communities, they read the initial PS piece and (wrongly) assumed this was about to happen again. And as people who, for the most part, genuinely share many of the impulses and desires of PS folks, they were dismayed at the thought that all their painstaking research and advocacy for better innovation systems and policy would not only continue to be ignored, but dismissed outright.

There's a broad understanding that PS is meant to be an applied discipline -- but 90% of the concern was that it would be an applied discipline that would only draw on the same set of economic theories that have already motivated innovation policy for the past few decades, and nothing would change as a result.

Thankfully, the community is thoughtful enough to not let that happen.

As with any metric, it comes down to what you're looking to diagnose -- and whether averages across the total system are a useful measure for determining overall health. If someone had a single atrophied leg and really buff arms, the average would tell you they have above-average muscle strength, but that's obviously not the whole story.

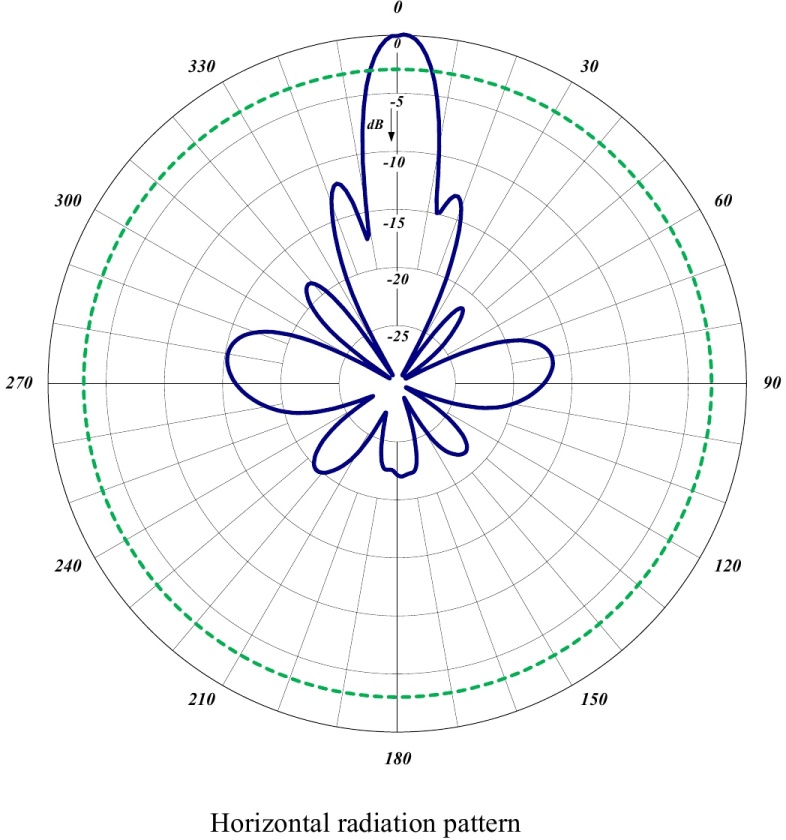

Same goes for innovation: if idea production is booming in a single area and dead everywhere else, it might look like the net knowledge production ecosystem is healthy when it is not. And that's the problem here, especially when you factor in that new idea production is accelerated by cross-pollination between fields. By taking the average, we miss out on determining which areas of knowledge production need nurturing, which are ripe for cross-pollination, and which are at risk of being tapped out in the near future. And so any diagnostic metric we hope to create to more effectively manage knowledge ecosystems has to be able to take this into account.

Also strongly recommend the adjacent possible work if you haven't seen it yet.

Good piece.

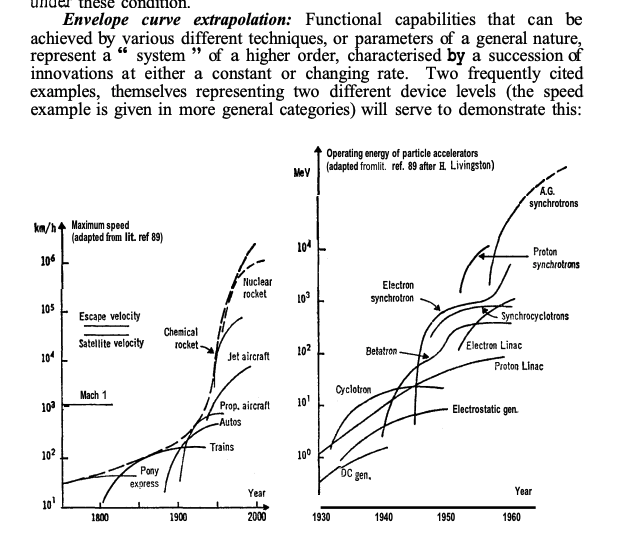

One of the main issues I have with economic approaches to knowledge production like Romer's is that they approach Knowledge as a singular entity that produces an aggregate economic output, as opposed to a set of n knowledges that each have their own output curves. In practice (and in the technological forecasting lit), there's a recognition of this fact in the modelling of new technologies as overlapping S-curves:

The S-curve approach recognizes that there is a point where the ROI for continued investment in a particular technology tapers off. So this means that we don't run out of Ideas, we just overinvest in exploitation of existing ideas until the cost-to-ROI ratio becomes ridiculous. Unfortunately, the structure of many of our management approaches and institutions are built on extraction and exploitation of singular ideas, and we are Very Bad at recognizing when it's necessary to pivot from exploit to explore.

Even worse, this is not only true for the structure of our industrial-commercial research, but for our basic research apparatus as well. Grants are provided on the basis of previous positive results, as opposed to exploration of net-new areas -- resulting in overexploitation of existing ideas and incentivized research stagnation.

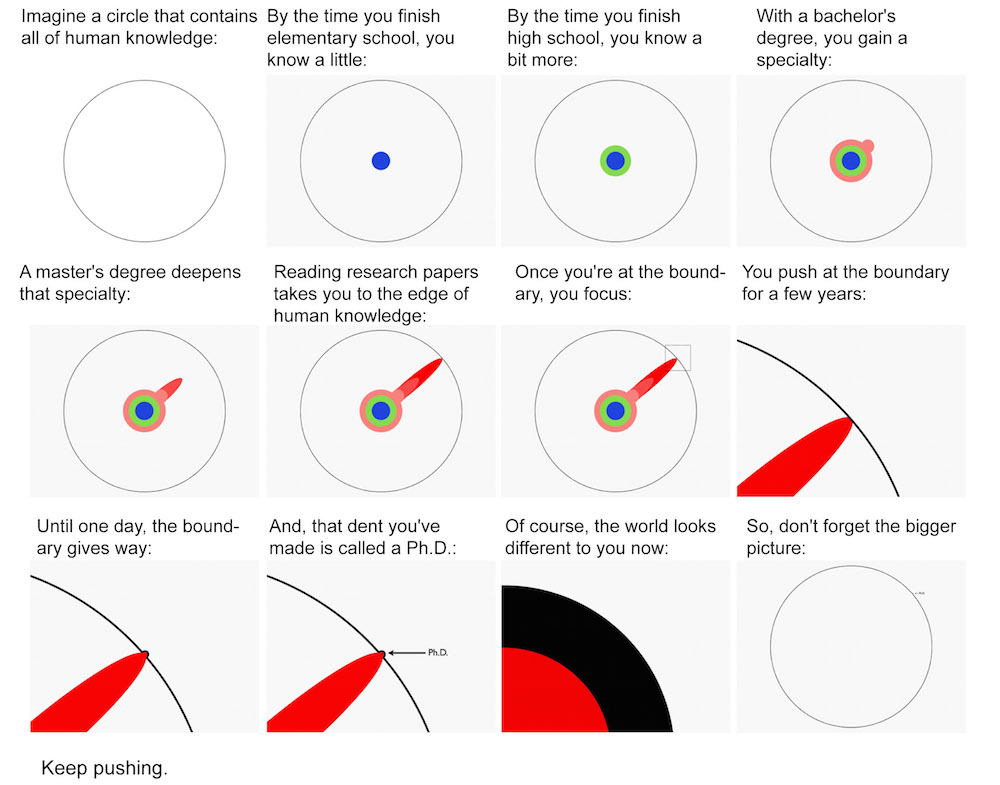

In practice, you can think of it like this comic...

except instead of a circle, our knowledge distribution looks like this

There are a few issues to parse here --

- Patents are a necessary part of motivation to commercialize in high-CAPEX industries

- Pharma companies take advantage of regulatory capture and abuse the IP system to eke out longer exclusivity periods than are typically allowed by law (e.g. making negligible changes and repatenting a drug); this has been a net drain on innovation

- No cap, benchmark, or standard on biotech pricing has allowed companies to slowly ramp up pricing far beyond what is considered reasonable (e.g. the gradual ramp-up to a Million Dollar Pill)

Prizes and direct subsidies already exist for high-CAPEX projects and are also a crucial part of the system as it exists today. Almost all biopharma research starts out as state-funded work out of universities or NIH, until it reaches a point where it's ready for trials and gets spun out into a business. The trials themselves are then often further subsidized. There's a lot of work and money that has to go into making biotech viable just because of how little we understand about fundamental biology.

The exclusivity rights conferred by intellectual property are exceptionally important in areas where the innovator's CAPEX requirements are high, but the cost to copycats is low -- like biopharma, energy, or even mining. The creation of a temporary monopoly engineers sufficient market value to make initial investment of high-risk capital on the order of hundreds of millions (if not billions) of dollars worthwhile and palatable (e.g. see https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/10161/6707/Record5.pdf; https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1019&context=facpubs ).

The rules were never supposed to apply to extremely low CAPEX industries like software, however -- hence why "abstract ideas" were excluded from intellectual property law and are often negotiated and renegotiated in the courts as incumbent monopolies and patent trolls try to use regulatory capture to maintain their status.

What does progress mean to you; what does your ideal progress-driven future look like? What are our daily lives like in that future?