All of James Rosen-Birch's Comments + Replies

There's a reasonable argument that we all lose out by calling programmers software engineers, given they lack the training in forensic analysis, risk assessment, safety factors engineering, and identifying failure modes that other engineering disciplines (i.e. civil, mechanical, materials, electrical) have to train in.

A lot of energy in the AI safety conversation goes into philosophizing and trying to reinvent from scratch systems of safety ... (read more)

This is an excellent subject area with a ton of material -- especially because so many 19th and 20th century social movements were so deeply tied with notions of social, economic, and technological progress, and often sought to use novel technologies to drive revolutionary change. In many cases, solidarity and freedom from hardship were seen as going hand-in-hand with modernity and industrialization.

The most exciting prospect here, imo, is building capacity to identify underresearched and underinvested foundational knowledge areas, filling those gaps, and then building scaffolding between them so they can cross-pollinate. And doing this recursively, so we can accelerate the pace of knowledge production and translation.

Hey there! I'm a startup founder and software engineer who is also one of the folks from the anthropology community who was initially skeptical of Progress Studies, so I can speak to their concerns -- which, to your point, largely came across as snide grumbling amongst academics. Unfortunately, as is often the case with tight-knit communities, their real concerns were understood implicitly and therefore not deemed necessary to communicate openly.

tl;dr, there's a pattern of (some) SV tech types only respecting two areas of knowledge: STEM, and economics (bu... (read more)

As with any metric, it comes down to what you're looking to diagnose -- and whether averages across the total system are a useful measure for determining overall health. If someone had a single atrophied leg and really buff arms, the average would tell you they have above-average muscle strength, but that's obviously not the whole story.

Same goes for innovation: if idea production is booming in a single area and dead everywhere else, it might look like the net knowledge production ecosystem is healthy when it is not. And that's the problem here, especially... (read more)

Also strongly recommend the adjacent possible work if you haven't seen it yet.

Good piece.

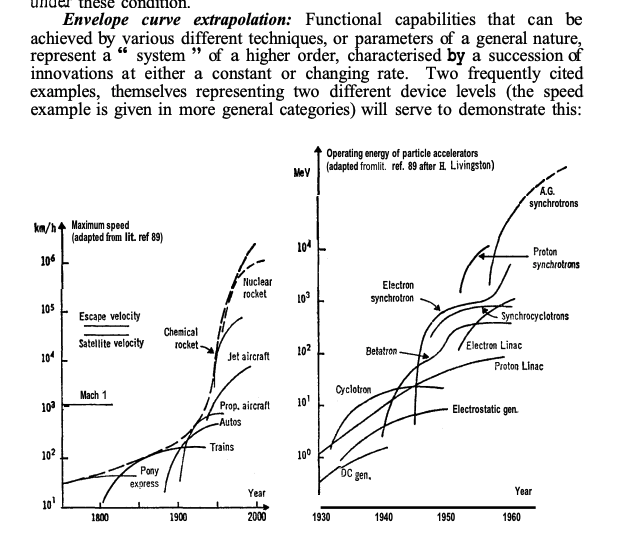

One of the main issues I have with economic approaches to knowledge production like Romer's is that they approach Knowledge as a singular entity that produces an aggregate economic output, as opposed to a set of n knowledges that each have their own output curves. In practice (and in the technological forecasting lit), there's a recognition of this fact in the modelling of new technologies as overlapping S-curves:

The S-curve approach recognizes that there is a point where the ROI for continued investment in a particular technology tapers off. So... (read more)

There are a few issues to parse here --

- Patents are a necessary part of motivation to commercialize in high-CAPEX industries

- Pharma companies take advantage of regulatory capture and abuse the IP system to eke out longer exclusivity periods than are typically allowed by law (e.g. making negligible changes and repatenting a drug); this has been a net drain on innovation

- No cap, benchmark, or standard on biotech pricing has allowed companies to slowly ramp up pricing far beyond what is considered reasonable (e.g. the gradual ramp-up to a Million Dollar Pill)

Pri... (read more)

The exclusivity rights conferred by intellectual property are exceptionally important in areas where the innovator's CAPEX requirements are high, but the cost to copycats is low -- like biopharma, energy, or even mining. The creation of a temporary monopoly engineers sufficient market value to make initial investment of high-risk capital on the order of hundreds of millions (if not billions) of dollars worthwhile and palatable (e.g. see https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/10161/6707/Record5.pdf; https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/cgi/vie... (read more)

What does progress mean to you; what does your ideal progress-driven future look like? What are our daily lives like in that future?