This Christmas my family decided not to exchange any gifts, but I ended up receiving one anyway: while idly scrolling twitter in the final days of December, I saw a page from a source that I had glanced at once, but hadn’t been able to find again because I’d very slightly misremembered what it said. I’d been on-and-off searching for it for the last four years, hoping to use it in the book I’m writing.

Specifically, the page is about the extraordinary inflow of migrants to London in the period when it grew eightfold — from an unremarkable city of a mere 50,000 souls in 1550, to one of the largest cities in Europe in 1650, boasting 400,000. I’ve written about that growth a few times before, especially here. It may not sound like much today, but it has to be one of the most important facts in British economic history. It is, in my view, the first sign of an “Industrial Revolution”, and certainly the first indication that there was something economically weird about England. It requires proper explanation.

In brief, the key question is whether the migrants to London — almost all of whom came from elsewhere in England — were pushed out of the countryside, thrown off their land thanks to things like enclosure, or pulled by London’s attractions.

I think the evidence is overwhelmingly that they were pulled and not pushed:

The English rural population continued to grow in absolute terms, even if a larger proportion of the total population made their way to London. The population working in agriculture swelled from 2.1 million in 1550 to about 3.3 million in 1650. Hardly a sign of widespread displacement.

As for the people outside of agriculture, many remained in or even fled to the countryside. In the 1560s, for example, York’s textile industry left for the countryside and smaller towns, pursuing lower costs of living and perhaps trying to escape the city’s guild restrictions.[1] In 1550-1650, the population engaged in rural industry — largely spinning and weaving in their homes — swelled from about 0.7 to 1.5 million. Again, it doesn’t exactly suggest rural displacement. If anything, the opposite.

There were in fact large economic pressures for England to stay rural. England for the entire period was a net exporter of grain, feeding the urban centres of the Netherlands and Italy. The usual pattern for already-agrarian economies, when faced with the demands of foreign cities, is to specialise further — to stay agrarian, if not agrarianise more. It’s what happened in much of the Baltic, which also fed the Dutch and Italian cities. Despite the same pressures for England to agrarianise, however, London still grew. To my mind, it suggests that London had developed an independent economic gravity of its own, helping to pull an ever larger proportion of the whole country’s population out of agriculture and into the industries needed to supply the city.

As for the supposed push factor, enclosure, the timing just doesn’t fit. Enclosure had been happening in a piecemeal and often voluntary way since at least the fourteenth century. By 1550, before London’s growth had even begun, by one estimate almost half of the country’s total surface had already been enclosed, with a further quarter gradually enclosed over the course of the seventeenth century.[2] A more recent estimate suggests that by 1600 already 73% of England’s land had been enclosed.[3] As for the small remainder, this was mopped up by Parliament’s infamous enclosure acts from the 1760s onwards — much too late to explain London’s population explosion.

Perhaps most importantly, people flocked specifically to London. In 1550 only about 3-4% of the population lived in cities. By 1650, it was 9%, a whopping 85% of whom lived in London alone. And this even understates the scale of the migration to the city, because so many Londoners were dropping dead. It was full of disease in even a good year, and in the bad it could lose tens of thousands — figures equivalent or even larger than the entire populations of the next largest cities. Waves upon waves of newcomers were needed just to keep the city’s population stable, let alone to grow it eightfold. In the seventeenth century the city absorbed an estimated half of the entire natural increase in England’s population from extra births.[4] If England’s urbanisation had been thanks to rural displacement, you’d expect people to have flocked to the closest, and much safer, cities, rather than making the long trek to London alone.

It’s this last point that I’ve long wanted to flesh out some more. The further people were willing to trek to London, the more strongly it suggests that the city had a specific pull. I’d so far put together a few dribs and drabs of evidence for this. Whereas towns like Sheffield drew its apprentices from within a radius of about twenty miles, London attracted young people from hundreds of miles away, with especially many coming from the midlands and the north of England. Indeed, London’s radius seems to have shrunk over the course of the seventeenth century, suggested that they came from further afield during the initial stages of growth.[5] Records of court witnesses also suggest that only a quarter of men in some of London’s eastern suburbs were born in the city or its surrounding counties.[6]

And this is where the source I’d misplaced — my unexpected Christmas gift — comes in. It describes how the more successful migrants to London from specific counties would band together to form annual feasting clubs, where often hundreds of diners would raise donations for their county of birth. These charitable well-to-do feasters established incomes for their home county’s clergy, secured apprenticeships for the county’s young people, or found ways to aid its poor. The feasts remind me a little of Japan’s “hometown tax”, designed to funnel some of the taxes paid by big city earners back to where they were born or grew up.

The county-specific London feasting clubs are very well attested for the late seventeenth century, largely as they often began with sermons, some of which were published. Along with the rise of Puritanism, which made such sermons more common, there are direct records of county feasts in London in the 1650s for Cheshire, Herefordshire, Hertfordshire, Kent, Northamptonshire, Nottinghamshire, Staffordshire, Suffolk, Warwickshire, and Wiltshire, as well as for London itself. For the 1670s and 80s, thanks to additional evidence from newspaper advertisements, we have direct evidence of feasts held for many more counties, and even the Isle of Man.[7] By contrast, the citizens of England’s third-largest city, Bristol, seem to have only had held feasts for the immediately surrounding counties of Gloucestershire, Somerset, and Wiltshire.

But that’s just the direct evidence. There are plenty of mentions of more, and earlier feasts. Although the sermon records in 1654 give us the names of only three, one of the preachers noted how sad it was “to hear of many county feasts” being held without sermons. Another noted that “these meetings of country-men are no new thing, though of later years they have been interrupted by reason of the sad calamities”.[8] It suggests county feasts had been common in the 1630s or 40s, before the civil war, with one 1660s preacher recalled giving a sermon to a feast for Devon in the early 1630s.[9]

Indeed, the earliest reference I’ve seen is from a letter sent from London in 1621. When mentioning a proposal to open Parliament with a sermon, the writer complains of how popular sermons have become, such “that all Cheshire men about this town, Staffordshire men, Northampton, Sussex, Suffolk, et sic de caeteris [and likewise for the rest] should have a meeting once a year at some hall and laying their money together have a feast, it must not be done without a sermon”.[10] Although the letter names only a handful of the counties being feasted, Cheshire and Staffordshire were especially far from the city.

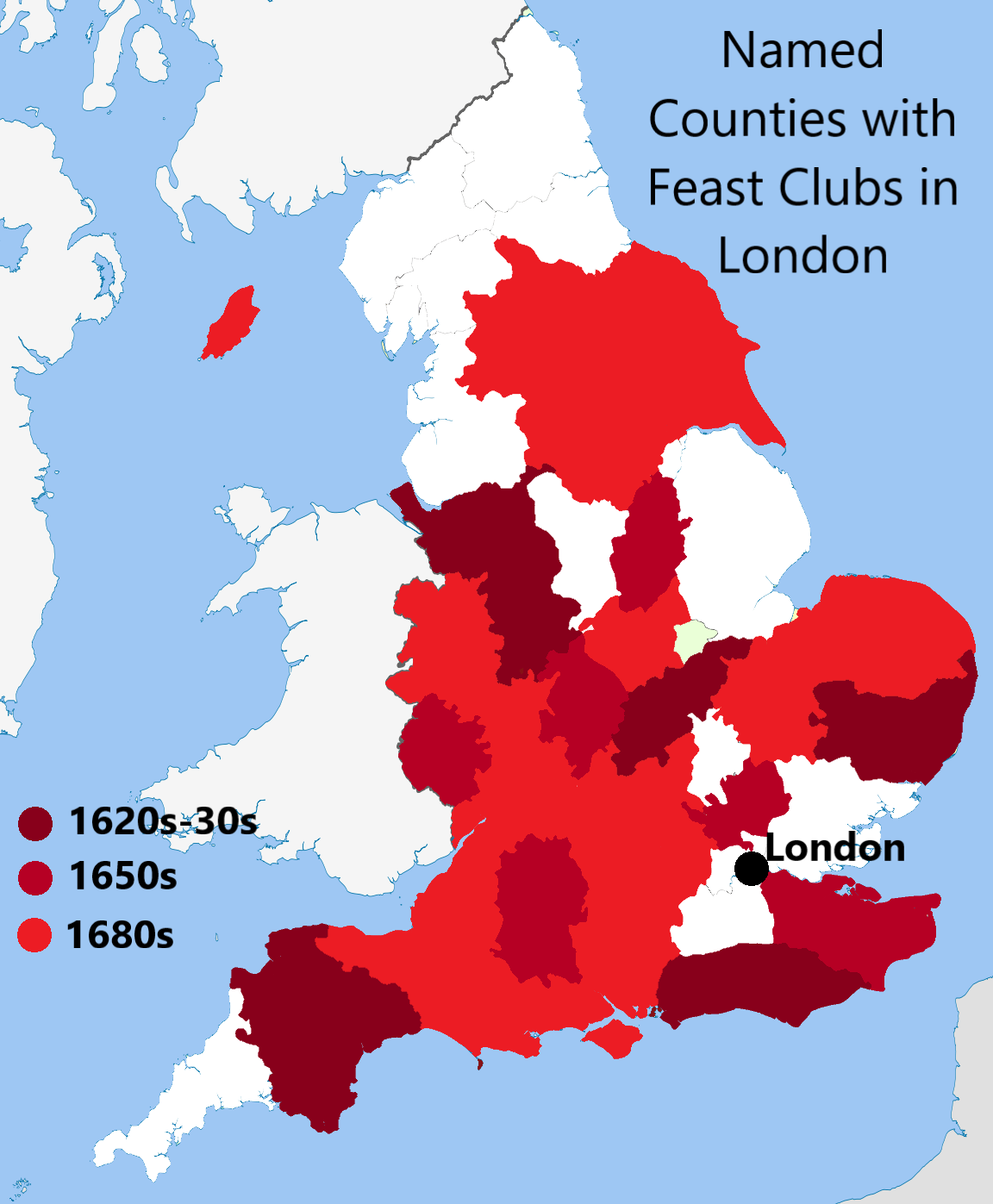

Here’s a map I’ve thrown together of the specific counties that were feasted, with the decade by which they were first mentioned.

The map already gives us some indication of where London’s migrants were coming from, but even then it’s just the tip of the iceberg. These were just the counties that were named in the very limited evidence we have. The hints of many more held without sermons and before the interruptions of civil war, as well as the fact that London’s radius for apprenticeships was seemingly highest in the earlier stages of its growth, suggest that the true map would show many more counties being feasted, and much earlier. And the migrations underlying them would likely have been earlier too — after all, the feasters were largely those who had already become successful in the city, and were thus able to afford the extravagance.

In the early eighteenth century, some counties appear to have become associated with particular coffee-houses, perhaps because they were the regular locations of the feasts. There were coffee-houses for Lancastrians, Northumbrians, and even Scots.[11] At the end of the eighteenth century, to have a fellow “countryman” was still to share a county of origin rather than a nation. The county feasts and the later county-specific coffee-houses a wonderful illustration of how migrants from the British countryside acted much like foreign immigrants occasionally do today, maintaining some of their ties with one another and with home.

If you stumble across more evidence or hints of London’s early pull, please do let me know!

- ^

Herbert Heaton, The Yorkshire Woollen and Worsted Industries, from the Earliest Times up to the Industrial Revolution (The Clarendon press, 1920), pp.54-56; John Oldland, ‘The Economic Impact of Clothmaking on Rural Society, 1300–1550’, in Medieval Merchants and Money, ed. Martin Allen and Matthew Davies, Essays in Honour of James L. Bolton (University of London Press, 2016), p.242

- ^

J. R. Wordie, ‘The Chronology of English Enclosure, 1500-1914’, The Economic History Review 36, no. 4 (1983), pp.483–505

- ^

Gregory Clark and Anthony Clark, ‘Common Rights to Land in England, 1475-1839’, The Journal of Economic History 61, no. 4 (2001), pp.1009–36.

- ^

Peter Spufford, ‘Population Movement in Seventeenth-Century England’, Local Population Studies 4 (1970), p.42

- ^

John Wareing, ‘Changes in the Geographical Distribution of the Recruitment of Apprentices to the London Companies 1486–1750’, Journal of Historical Geography 6, no. 3 (1 July 1980), pp.241–49; Spufford, p.44; Roger Finlay, Population and Metropolis : The Demography of London, 1580-1650, vol. 12, Cambridge Geographical Studies (Cambridge University Press, 1981), p.66

- ^

David Cressey, ‘Occupations, Migration and Literacy in East London, 1580-1640’, Local Population Studies, no. 5 (1970), p.58

- ^

Newton E. Key, ‘The Political Culture and Political Rhetoric of County Feasts and Feast Sermons, 1654–1714’, Journal of British Studies 33, no. 3 (July 1994), pp.223–56; also see Peter Clark, British Clubs and Societies 1580-1800: The Origins of an Associational World (Oxford University Press, 2000), ch.8

- ^

Ibid., pp.274-5

- ^

Key, p.230

- ^

John Chamberlain, The Letters of John Chamberlain, ed. Norman Egbert McClure, vol. II, Memoirs, XII, Part II (American Philosophical Society, 1939), p.408

- ^

Brian Cowan, The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse (Yale University Press, 2008), p.169

Very interesting topic. How widespread is the “pull” idea? When I first read about it in an essay from you a while ago, I thought it was kind of a niche view, but I've been reading Robert Allen's The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective and he seems to have the same view, so maybe not so niche?

Wow I should really login more often. 9 months late, but here goes. Yes, it is definitely a position that already existed, as per Allen. But the push thesis is by far the most popularly known one, and one that I think a lot of historians are still very sympathetic to, having been brought up on the Marxist historians (who were often very good, but had some blindspots)