This post contains spoilers for a science-fiction novel, but I won’t tell you which unless you want to.

Here’s why. Spoilers matter if you’re going to read the book and remember what I told you about it. But chances are that you’ll never read that book — it came our several years ago, it’s long, it’s full of confusing made-up words, and it deals with highly abstract concepts in philosophy and physics. I personally greatly enjoyed it, but I wouldn’t recommend it to most people I know.

Even if you do read that book someday, it’s unlikely that you’ll recognize it as the book discussed in that one blog post you once read. This is all the more true if I don’t name the book and remain somewhat vague in what I write.

And since I would like you to read my essay — as the point is to discuss not the book, but technological progress — I don’t want to paste a big SPOILER ALERT banner at the top that would scare people away. In the unlikely event that you’re currently reading the book, you’ll probably recognize it quickly enough from hints like the image above of an icosahedron in the sky, and the descriptions below (I don’t start with spoiler-y things, and I’ll warn you when I do). In that case you have my blessing to stop reading.

If you nevertheless want to know which book it is (perhaps because you agree with me that spoilers don’t really matter, or because, based on the hints, you’re pretty sure you’ve read it and want to confirm), then go to this footnote[1] and click the link.

The novel we’re talking about is set on a planet that isn’t Earth, but resembles it. The people aren’t exactly like us, yet they are human. Their history mirrors ours: there was an ancient city-state akin to Athens where philosophy and mathematics flourished, and then an equivalent to our Roman Empire that absorbed it. A thousand years after the fall of the empire, a great age of technology began, in parallel to our Scientific and Industrial Revolution. Engineers and scientists held a lot of influence, until a number of catastrophic events — we never really know what, but they involve wars, genocides, and dangerous technological weapons — led to a total reorganization of society and especially the scientific world.

All of this happened thousands of years before the story. The time of the catastrophic events seems to coincide roughly with our 20th and 21st centuries, so we can infer that the book is set more than 3,700 years into the future.

And… what’s striking is how similar that world is to ours. The people drive cars and trucks, use smartphones and the internet, practice a variety of orthodox and newer religions. (Of course, all of those things have made-up names in the novel.) There are many references to cities, languages, and countries that grew large and then died off, but the book gives the distinct impression that the world over those 3,700 years has been more or less stagnant. Things ebbed and flowed while almost no fundamental change happened.

This impression is heightened by the very particular setting of most of the events in the book. The main characters are young scientists, mathematicians and philosophers — i.e., the people whose work is to cause fundamental change in society. They live in special cloistered places that are reminiscent of monasteries. In fact the major reorganization that happened 3,700 years prior was mostly about isolating all these thinkers from mainstream society.

So if you are, like the main characters, a nerd, you can go to the monastery and devote your life to studying philosophical or mathematical problems while obeying a strict discipline. No advanced technology, for instance. No computers, in internet. And most notably, no going outside or sharing information with the non-science world, except at specific intervals which (depending on the monastery) range from 1 year to 1,000.

(At this point, if you have heard of the book at all, you probably know which one it is. Note that there haven’t really been any spoilers so far; everything above is basic worldbuilding, revealed within the first few chapters.)

This means that the characters in the book spend very little time thinking about the outside world. Of course, it’s a novel, so eventually Things Happen and they have to leave their cloister, and that’s when we learn all about how that future world is basically like ours, with almost identical technology. Which is somewhat puzzling, until you realize that the purpose of putting all the thinkers into cloistered monasteries was to ensure that very outcome.

At a few points in the 3,700-year history between the reorganization and the present, the people in the monasteries, who spent all their time thinking and solving problems, managed to invent some disruptive technologies. In three cases this led to major upheavals in which the monasteries were attacked by the outside world.

The first disruptive tech was some sort of fundamental physics manipulation that altered the properties of matter, probably an analog to advanced nanotechnology. After the conflict, most objects made of the altered matter were forbidden (with a few grandfathered exceptions).

The second was advances in genetic engineering. After the conflict, the whole science world was reorganized, with stricter discipline, removal of computer technology — there’s a special segregated caste of sysadmins that takes care of the computers in a few monasteries — and the abolition of genetic engineering (with a few grandfathered exceptions).

The third is story-relevant and kinda complicated, so I won’t describe it.

The end result is that the scientists at the time of the novel are rather… stunted. Imagine trying to discover fundamental truths about the universe without computers, film, ability to travel, or, precision tools (with a few grandfathered exceptions). You would end up doing mostly theoretical work, as well as astronomy. And since all the smart nerds are in those monasteries, technology would stagnate.

Which is exactly what you want, if the world almost ended a couple times because of nuclear weapons or genetic engineering gone rogue.

Now here are the major icosahedron-shaped spoilers. You can skip the next three paragraphs if you really want to, but I’m going to remain vague.

At some point during the story, the planet receives visitors from other worlds — including Earth. They arrive in a giant spaceship shaped like a Platonic solid, and then everyone understandably freaks out, especially since the aliens don’t seem particularly peaceful. Mainstream society remembers that there are several thousand nerds in those monasteries and asks them to come out and help — an extraordinary event that has happened only once, when an asteroid threatened the planet 2,500 years prior.

Outright conflict erupts between the planet and the aliens. This is bad, because those aliens clearly have advanced technology: they managed to build that spaceship, and to travel between universes! But the planet, thanks in large part to the smarts of the nerds and that mysterious technology I alluded to above, eventually prevails.

There is some irony here. To ensure stability, the planet stunted its own technological progress, which made it vulnerable when more advanced visitors came. But fortunately, it didn’t stunt itself so much that it was powerless. After the events involving the aliens, the authorities recognize this, and dismantle the cloistered monastery system: now, just like 3,700 years ago, the scientists and philosophers will be free to walk among the rest of society.

What does this all say about our relationship with technological progress? A few things.

First, there’s the question of whether there’s a benefit to slow down progress. The world of the novel hasn’t fundamentally changed in thousands of years. It mostly uses the same technologies as before. There’s even some talk (by one of the non-scientist characters) on how that’s preferable to some degree, because at least they can understand the tech. Perhaps some fancy quantum nuclear something something power source would work better than a combustion engine, but the combustion engine can be repaired by just about any mechanic.

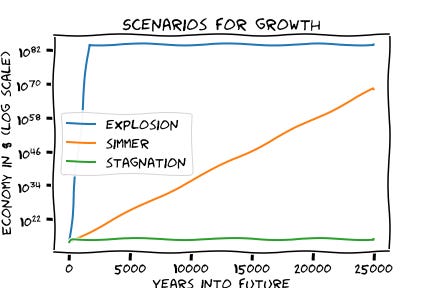

Overall, the people outside the monasteries seem to live okay lives, on par with ours. They’re all drugged with a naturally-occurring substance that makes everyone feel fine at all times. Until the Disrupting Events in the story, it looks like a society that found a way to self-perpetuate without existential catastrophe or untold suffering (that we know of). There is still the occasional creation of new knowledge in the monasteries that gets released into the world every 10, 100, or 1,000 years, so it’s also not exactly stagnation. It reminds me of the “simmer” scenario described in this post by Dwarkesh Patel: a long episode of slow growth that avoids both pure stagnation and an explosion that quickly reaches the physical limits of the planet or universe (and would likely mean massive cultural change that not everyone would be on board with!).

Of course, the fact that it happens in a novel is not, in itself, evidence that it is plausible or desirable in the real world. It’s a limitation of fiction: it’s far easier to depict a stagnating or simmering world than an explosive one.

And then there’s the fact that the Disruptive Events do happen. The book shows the perennial risk of technological stagnation: it works only if everyone does it.

The novel never quite makes clear what the political structure of the world looks like. (The justification is that the people in the monasteries simply do not care.) There’s some sort of planet-wide coordinating organization, though we don’t know if it’s something like the United Nations, a world government, or simply a single superpower country that can control the other ones. And then the monastery system exists in parallel, but is also well-coordinated across the world.

On Earth, as of 2022, we don’t have anything with that level of coordinating ability. Even if the United States and the West decide not to build some new tech (such as artificial general intelligence), China might. Or vice-versa. Or India, or Russia, or Saudi Arabia. We live in a multipolar world, and in such a world, giving up on progress means that some other power will just overtake you and perhaps conquer you, as if they were further along the tech tree in a game of Civilization.

In the book, they thought they lived in a unipolar world — until the Disruptive Events happened. And then they were saved in extremis by technology that they had grandfathered in.

Is it worth taking seriously the risk of major disruption like contact with non-human technology? I have no idea. I feel like it’s something at least worth considering. The point of technology to to give ourselves better ability to react to new situations, which is beneficial in general and in the highly hypothetical case of interacting with foreign tech.

Still, there’s a lot of talk that certain kinds of tech (AGI, bioweapons, etc.) should be limited or banned, because of their great risks. So suppose we agreed that progress ought to be slowed down. Is the monastery system of the book a good way to do it?

It’s hard to imagine scientists and philosophers being completely cut off from society. But we already have a weird system called academia that the rest of the world doesn’t fully understand. And academia, as many people like to point out, is somewhat inefficient and full of problems. So we could potentially just make it a bit more inefficient, accentuate its problems, make it even more illegible to mainstream society — and there we go! We’d have a wonderful way to waste the lives of smart, curious people while providing no useful innovation at all, thereby ensuring the safe continuation of civilization.

Then the United Nations would just have to ban private research labs from China to the US, and we’d be safe forever. Or until the aliens show up.