The triumph of science and reason that seeded the industrial revolution was as much a story of towering individual geniuses as it was of the small number of specific places that produced and nurtured them. The so-called “Great Enrichment” happened only once and began in only a handful of places; today, most world-changing innovations still emerge from a tiny number of especially-productive “superstar” cities.

Yet much like the lives of the generational inventors and scientists who walk their streets, these “Centers of Progress”–as Cato Institute author Chelsea Follett calls 40 cities that shaped the modern world in a new book–often do not last long at the absolute frontier of economic, scientific, or social achievement. As Matt Ridley noted in the book’s introduction, “global progress depends on a series of sudden bush fires of innovation, bursting into life in unpredictable places, burning fiercely, and then dying rapidly.”

Schumpeter argues that both the creation and death of firms are key to driving innovation and growth in the long-run; so, too is the cycle of individual cities displacing leading centers of progress, only to later be usurped themselves. Fixing the policy mistakes of today’s superstar cities is indeed important, but perhaps we are neglecting the many second-tier regions across the country, some of whom will be tomorrow’s superstars.

Consider the dramatic extent to which the economic geography of the United States has changed over the past century. Of the ten largest cities by population in 1900, only three remain in the top ten today. Detroit was the wealthiest city in the nation in 1950 on a per-capita basis, while San Jose had yet to crack 100,000 residents. The next 50 years would see the hollowing out of once-thriving Rust Belt metros and the rise of new technology hubs on both coasts. Today, another great shift is taking place as wealth, talent, and investment flow to booming Sun Belt cities and their surrounding suburbs from coastal cities that have priced out families.

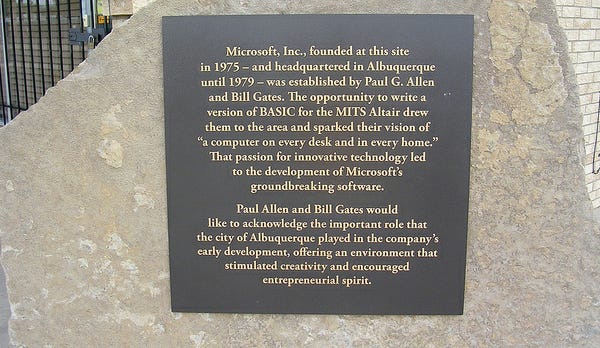

The rise of the knowledge economy and its tendency to tightly cluster were deep, structural forces probably destined to reshape the country’s economic map in some way, but where new hubs took root was often a highly contingent outcome determined by the decisions of just a handful of people. As economist Enrico Moretti notes in his book, The New Geography of Jobs, Bill Gates and Paul Allen’s fateful decision to move Microsoft from Albuquerque to the Seattle area in 1979 changed these two cities’ economic trajectory for decades. On paper, Albuquerque and Seattle both had decidedly unremarkable economies in the late 1970s and the latter had been hit hard by population loss over the prior decade. Gates simply wanted to live closer to home. It is not far-fetched to imagine an alternate scenario in which Albuquerque emerges as a global hub of tech talent and Seattle remains a relative backwater.

To the many of us who see continued economic progress and ending the “Great Stagnation” as moral imperatives, the failure of the most innovative metro areas to accommodate new people and the ideas they bring is blatant economic self-sabotage. Indeed, one famous estimate from Moretti and fellow economist Chang-Tai Hsieh finds new restrictions on housing construction since 1960 in just New York City, San Francisco, and San Jose are costing the average American family more than $3,600 per year. But while the housing policy failures of regions like the Bay Area are costing us all dearly, these cities’ place at the top of America’s economic hierarchy is not an inevitable fact of life. For those of us who do not live in a high-cost superstar region, campaigning to force them to remain open to new people, ideas and technologies is a tempting idea that would benefit us all, but we would also benefit from channeling at least some of that energy to our own backyards.

The contingency of a take-off story like Seattle’s should not cause you to throw your hands up and conclude the take-off of future innovative hubs is mostly random. Rather, it should demonstrate the effect even very small changes can make in the long-run. Subtle differences in cultural attitudes or minute regulations may ultimately separate leaders from followers.

Your city may be at just such a crossroads at this moment. The flexibility of your city’s housing policy towards densification may determine whether future innovators or entrepreneurs can cluster together sufficiently to share ideas. Your local university’s ability to truly integrate with the local economy will influence whether talented graduates leave or put down roots and build their professional and intellectual networks locally. Even city leaders’ attitudes towards new technology and experimentation may shape your city’s trajectory. Not all of these areas are viewed as “innovation policy” per se but are arguably just as important as cities’ efforts to forge new clusters themselves.

There is good news: unlike in the Bay Area, where supervisors blocking new housing or self-driving cars are national villains and local debates are bitter and entrenched, odds are few people in your city are even paying much attention. You can likely make a much greater difference than you think.

The study of progress almost always focuses on the extremes–the stories of the lone inventor or the one-off lab. But “place” matters just as much, and world-shaping ideas, companies, or technologies often take root in unexpected places. The next one may very well originate in your own backyard, if you are willing to help.