Progress as an art worth watching.

In the 1870s, pain, anguish, and helplessness were common descriptors of health. The United States was emerging from the bloody Civil War, where battlefield doctors saw death and horrifying disabilities on a mass scale. Nearly one in three children died before the age of five.[1] However, by the turn of the century, life expectancy had jumped by over 9 years.[2] Two paintings by Thomas Eakins, painted 15 years apart, bring us into this world and speak to the drivers of this spectacular improvement in health.

In 1875, Thomas Eakins captured a surgical clinic at Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College, where he had been a student himself before focusing on artistic ambitions. The surgeon, Dr. Samuel D. Gross, is performing and explaining his craft to students at the medical school. The eye is drawn to the pallid, sickly center of the painting, where the sharp red blood stands out on the hands of the small circle of medical attendants and drips from the hands of the lecturing surgeon.

Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic), 1875, by Thomas Eakins (American, 1844–1916)

Note the dark suited Victorian street wear of the medical attendants, with collars, ties, and suit jackets—a far cry from sanitary apparel. Although the beginnings of germ theory had been discovered by the mid-19th century by pioneers such as Ignaz Semmelweis in Austria, Louis Pasteur in France, and Joseph Lister in the UK, the theory faced a hard road to acceptance among medical practitioners. Infectious disease and poor sanitation caused most deaths through pneumonia, tuberculosis, and various gastrointestinal diseases.[3]

The most intense drama of the scene comes from the dark female figure behind the surgeons. She hides her head in trauma and horror at the scene before her. Perhaps she is the patient’s mother. Unable to leave her precious child but also unable to endure the difficult scene. Her placement in the painting adds a note of anguish and helplessness to the surgery.

Mothers especially were subject to anguish during this period, where over a third of children died before age 5. In 1875, at the time of the painting, the child mortality rate had been rapidly climbing because of the fourth cholera pandemic, smallpox outbreaks, and yellow fever, diseases caused by poor sanitation and poor infection protocol.[4] Common treatments were often worse than the disease, such as bloodletting, purging, and opium.[5]

However, the grim world of Eakins’s first painting was on the cusp of remarkable improvement.

Gradually, the acceptance of the discovery of bacteria led to new improvements in sanitation. Public health initiatives created sewers, protected and maintained clean water, began pasteurizing milk, and promoted hand washing. Together, these led to higher survival rates for infants and children. Child mortality took a steep dive immediately, continuously dropping for over 30 years from its heartbreaking level in 1880.

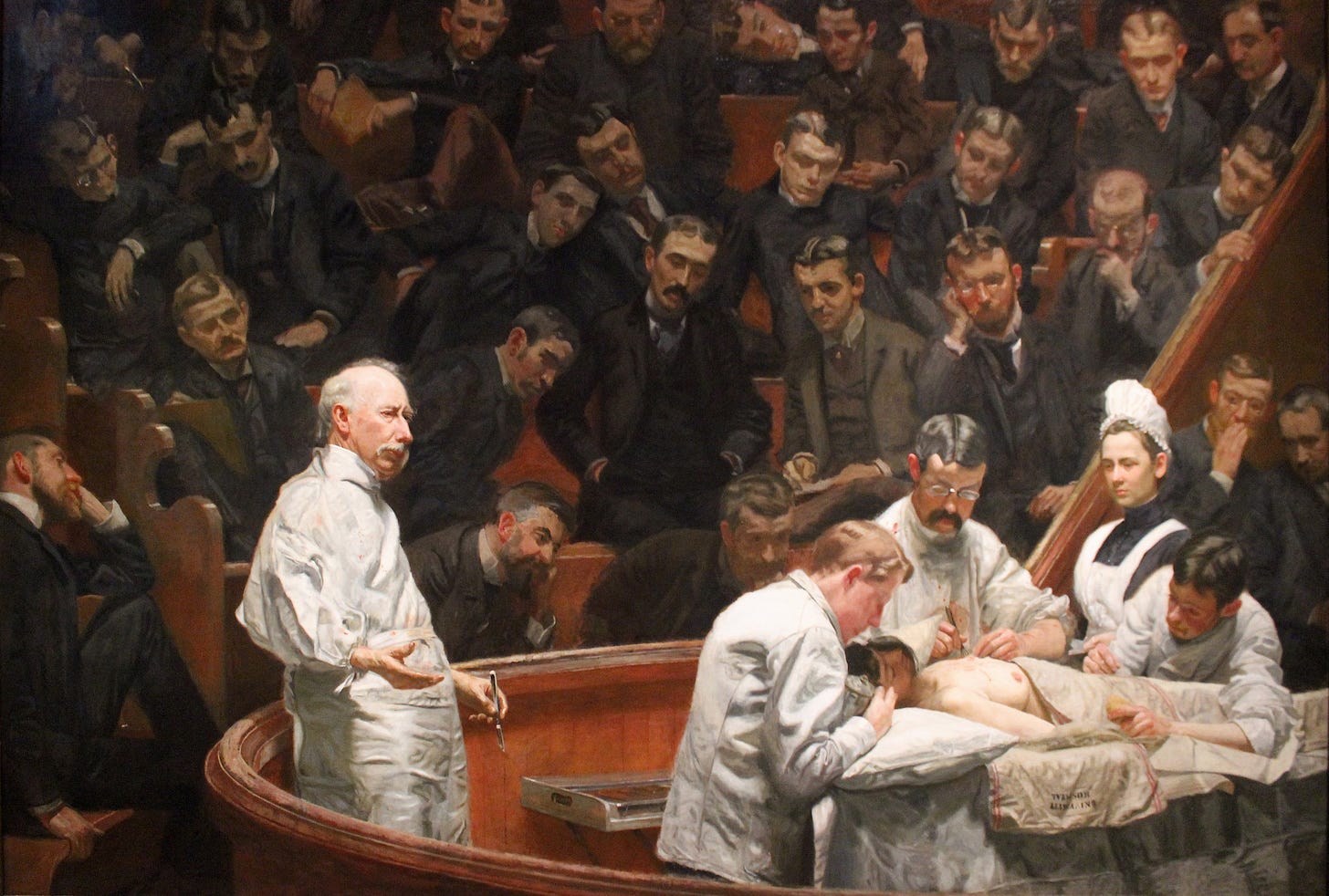

Medical schools had been expanding since the early 1860s, leading to large-scale training and greater popularity of surgical audiences. Only 14 years later, Eakins again painted a surgical clinic scene, this time of Dr. D. Hayes Agnew, an illustrious surgeon nearing retirement.

The Agnew Clinic, 1889, by Thomas Eakins (American, 1844–1916)

This feeling in this painting is a high-contrast departure from the previous clinic. The surgeon and his staff now dominate the picture, not the placid patient on the operating table. The medical attendants have switched to white, sanitary, surgical dressing instead of the dark velvet suits of the previous painting, highlighting an early victory of germ theory.

The surgeon himself is now the central figure, basking in light compared to the gallery behind him. He is clearly holding court, standing aloof from the surgery itself, his clean hand extended in a gesture, as he confidently conducts a wonderous and engrossing display. The audience behind him is more numerous than the previous clinic, filled with focused and interested medical students. Some students rest their head on their hand or on their neighbor’s shoulder, and all eyes are focused on the operation.

The orderly, attentive students reflect a larger change in the practice of medicine. The invention of new diagnosis equipment during this period revolutionized the ability of physicians to make repeated, measured observations, to keep records, and to approach their trade with more scientific precision.

Although the stethoscope had already been invented by the first painting, many others followed by the end of the century—the ophthalmoscope for the eyes, the laryngoscope for the throat, a variety of specula, the medical thermometer, and the X-ray. The achromatic microscope, championed by germ theory scientist Joseph Lister, illuminated the study of bacteria and its role in infection. The most influential surgical advancement, anesthesia, also became more precise between the two paintings. In the first painting, the patient is sedated with a cloth held over the face, but a mask delivers a more targeted application by the second clinic.

The 19th century marked the professionalization of medicine and the standardization of treatments. The growing supply of physicians formed medical societies and improved precision in their trade which led to new medical journals to debate and standardize treatments.

The lone female in Eakins’s second clinical painting presents revolutionary counterpoint to the anguished mother in the first painting. Stoic and calm, dressed in sterile surgical garb, the assisting nurse is attentive and at the ready. Women contributed to professionalization of medicine via an explosion in the number of nursing schools, increasing from merely 15 in 1880 to 432 by 1900. The number of nurses grew 10-fold in the ten-year period from the 1880 census to the 1900 census.[6]

The assisting nurse in the painting has been identified as Mary V. Clymer. Her placement in the painting as a competent and dispassionate professional showcases the rational focus of medicine as science, as well as the growing authority of women as nurses in medical practice. She left two volumes of dairies detailing her instruction and practices during this period, in which she wrote, “We must always be dignified & grave [when assisting a surgery] never forgetting that all we are trying to do is for the good of the patient” (Clymer, v.2., p52). Far from the helpless mother on the edge of the action, Clymer describes her actions as member to a professional medical class.

These two paintings offer a hopeful contrast. Whereas we begin with pain and suffering, we move to hope and progress. The surgeon stands apart as a hero, a symbol of the triumphant conquering of nature by humanity. This progress grew from an unrelenting pursuit to understand the bacterial world, the ingenuity of innovation in the tools of medicine, and the united efforts of medical professionals in the true practice of science— asking questions, making records, and fostering debate about their answers. It is no small wonder the vast audience of Eakins’s second painting looks on in rapt attention- this is an art worth watching.

[1] UN DESA, and Gapminder. "Child Mortality Rate (under Five Years Old) in The United States, from 1800 to 2020*." Statista, Statista Inc., 17 Jun 2019.

[2] UN DESA, and Gapminder. "Life Expectancy (from Birth) in The United States, from 1860 to 2020*." Statista, Statista Inc., 31 Aug 2019,

[3] Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families; Field MJ, Behrman RE, editors. When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. Washington (DC): National

[4] Child mortality in the United States 1800-2020. Published by Aaron O'Neill, Jun 21, 2022 Statista.

[5] Daly WJ. The black cholera comes to the central valley of America in the 19th century - 1832, 1849, and later. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2008;119:143-52; discussion 152-3.

[6] Rothstein, William G, 'Medical Care and Medical Education, 1825–1860*', American Medical Schools and the Practice of Medicine: A History (New York, 1987; online edn, Oxford Academic, 12 Nov. 2020), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195041866.003.0010, accessed 20 Oct. 2023.

[7] To read more about the specific surgical advancements in these paintints, check out this article: Nancy Minty, Collections Editor “The drama of the operating theater: Thomas Eakins’ medical paintings and clinical fact” December 4, 2019

Since you've highlighted the women in these paintings, it's worth noting that one of the first scientific studies advocating the use of masks in surgery was written by Alice Hamilton, a Chicago physician, in 1905. Quoting my article here (it may be paywalled):

Thank you for sharing! I love the tagline on your article about masks bringing us together over the past 400 years, much like medical progress. Also, I'm having amazing thoughts about progress that you can directly link me to accessing this article from 1905.