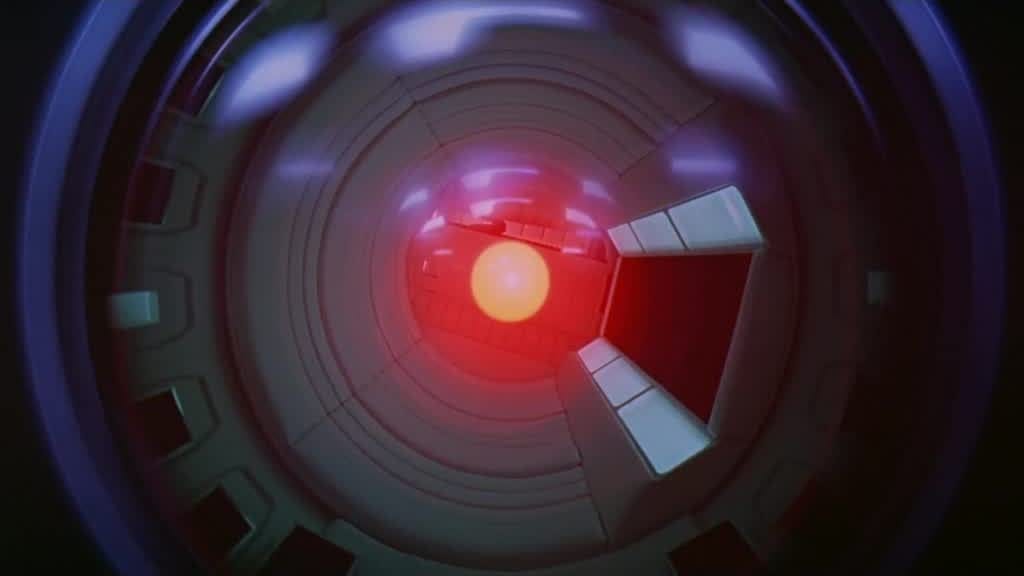

Picture a computer that surpasses human intelligence on every level and can interact with the real world. Should you be terrified of such a machine? To answer that question, there's one crucial detail to consider: did this computer evolve through natural selection?

The reason is simple: natural selection is a brutally competitive process, which tends to produce creatures that are selfish and aggressive. While it is true that altruism can evolve under certain conditions (like kin selection or reciprocal altruism), the default mode is cutthroat competition. If they can get away with it, most organisms will destroy rivals in a heartbeat. Given that all of us are products of evolution, there's an ever-present temptation to project our own Darwinian demons onto future AI systems. Many folks today worry about AI scenarios in which these systems subjugate or even obliterate humanity—much like we’ve done to less intelligent species on Earth.1 AI researcher Stuart Russell calls this the “Gorilla problem”. Just as the mighty gorilla is now at our mercy, despite its superior brawn, we could find ourselves at the mercy of a superintelligent AI. Not exactly comforting for our species.

But here's the catch: both humans and gorillas are designed by natural selection. Why would an AI, which is not forged by this process, want to dominate or destroy us? Intelligence alone doesn’t dictate goals or preferences. Two equally smart entities can have totally different aims, or none at all—they might just idly sit there, doing nothing. Critics of AI doom have sometimes sounded this note of reassurance. Even if AIs outsmart the smartest humans, according to AI pioneer Yann LeCun, they won’t share our vices because they didn’t evolve like we did:

Because AI systems did not pass through the crucible of natural selection, they did not need to evolve a survival instinct. In AI, intelligence and survival are decoupled, and so intelligence can serve whatever goals we set for it.

But what if that assumption is wrong? A while ago I came across a long and fascinating paper by Dan Hendrycks , director of the Center for AI Safety, with an ominous title: “Natural Selection Favors AIs Over Humans”. Many AI doomsday scenarios tend to be pretty speculative and short on detail, but to his credit, Hendrycks presents a clear and specific scenario of how things could go terribly wrong.

In Hendrycks’ view, AI systems are already undergoing natural selection in the curent AI race, being subjected to “competitive pressures among corporations and militaries”. Unfortunately, this means they’ll develop selfishness and a hunger for dominance after all, just like other evolved creatures. Now that got my attention, because I always assumed that natural selection was the only way (or at least the most plausible one) to bring about selfishness. If Hendrycks is right, we’re in trouble. If our sluggish, carbon-based brains have to compete against silicon-based creatures that are infinitely faster and more intelligent, but equally selfish, then we’re toast.

When you find a paper that seems to confirm your worst fears, what do you do? Write a paper-length response to see if you can disprove the terrifying prediction, of course! That’s what I did. I’m no AI expert, but I’ve published on biological and cultural evolution, so I teamed up with my friend Simon Friederich, a German philosopher who has published on AI safety. This was a somewhat competitive collaboration (we’re evolved creatures after all), since Simon is much more worried about AI risk than I am and we have been trying to persuade each other for the past few years. Hopefully our respective biases have cancelled out in the final result. The paper is now published in Philosophical Studies, in a special issue about AI safety. So will selfish machines subjugate humans? In this post I outline Hendrycks’ argument and our critique.

The Algorithm of Natural Selection

Evolution by natural selection isn’t limited to carbon-based life; it’s substrate neutral, meaning it can manifest in various media. Philosophers like Daniel Dennett even call it an “algorithm,” a simple recipe that works whenever minimal conditions are met. Biologist Richard Lewontin defined these conditions as (1) variation in traits, (2) heritability of traits, and (3) differential survival and reproduction based on these traits. That’s it. This deceptively simple set of criteria is all it takes for natural selection to work its magic. Dan Hendrycks argues these conditions are already met for AI systems. Let’s take them in turn: (1) there is variation in different AI systems, with Large Language Models like GPT, Claude, DeepSeek, Gemini, etc. (2) There are different generations of AI systems, from GPT-2 to GPT-3 and GPT-3.5, forming lineages of descent; (3) the companies with the best and most powerful AIs will win the race, while the other ones will be left behind (Sorry, Europe and Mistral). The market constantly weeds out unsuccessful AIs and preserves the best. So far we agree.

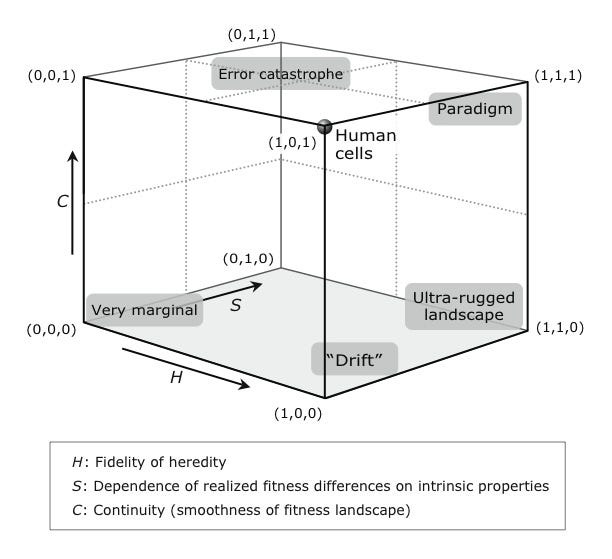

But then Hendrycks takes a leap. That AIs evolve through natural selection is extremely worrying, he argues, because natural selection tends to produce selfish, deceptive and dominant creatures. Here’s where we diverge. Lewontin’s conditions describe the bare minimum for natural selection, but there’s a wide range of parameters. Philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith has developed a visual framework called Darwinian spaces for distinguishing between paradigmatic and marginal cases of natural selection. Examples vary along dimensions like the fidelity of replication or the smoothness of the fitness landscape (intuitively, how gradually or suddenly your fitness changes with each genetic tweak). A Darwinian space typically represents three dimensions, but you should think of it as a multidimensional space, projected in 3-D. In the upper right corner of the picture below, you find paradigmatic cases of natural selection; as you further move away from that point, you get more marginal cases but still natural selection. One marginal example is computer virus evolution: the most infectious survive, but often the viruses don’t mutate and have been crafted by an intelligent designer. Another is the cultural evolution of empires: successful empires conquer neighboring nations or tribes, but you will find no clear “reproduction” events, in which a parent empire spawns tiny offspring.

Darwinian spaces are a powerful tool to think about the varieties of natural selection. Our paper points out a number of disanalogies between biological evolution and AI evolution in the Darwinian space, the most important of which is the dimension of blind vs. guided selection. Lewontin’s criteria don’t specify what accounts for differential reproduction, only that it should be non-random. The best way to understand this difference is domestication. In the early chapters of On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin famously warmed up the reader to the creative power of natural selection by first discussing “methodical selection” by human breeders, which he then contrasts with nature’s unconscious selection:

As man can produce and certainly has produced a great result by his methodical and unconscious means of selection, what may not nature effect? Man can act only on external and visible characters: nature cares nothing for appearances, except in so far as they may be useful to any being. She can act on every internal organ, on every shade of constitutional difference, on the whole machinery of life. Man selects only for his own good; Nature only for that of the being which she tends.

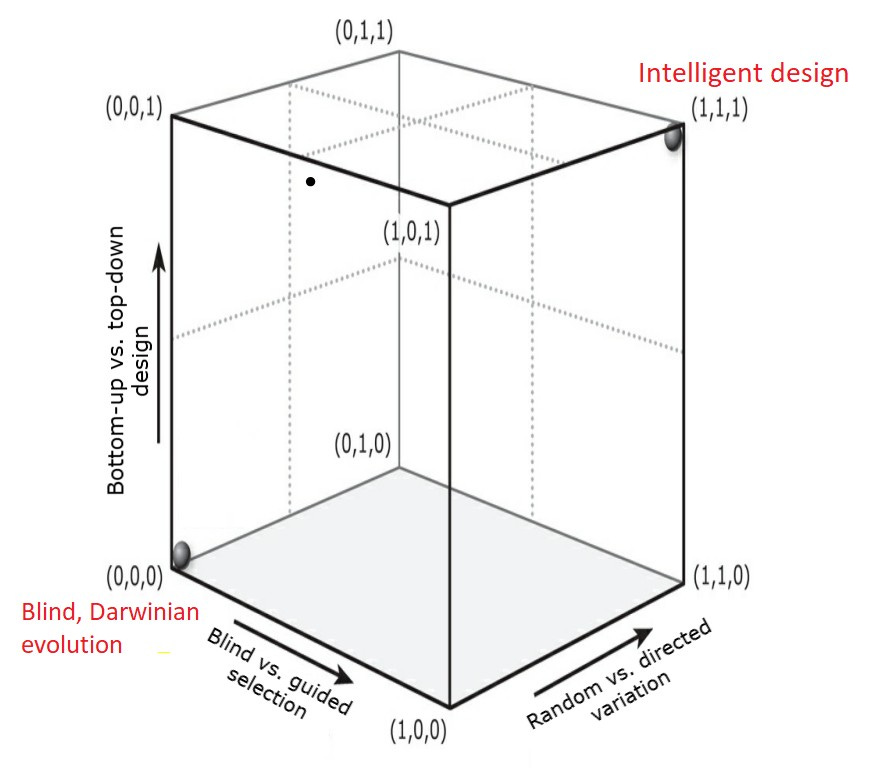

Is artificial selection by human breeders still a form of natural selection? It depends on your definition. There is no essence of natural selection, or as Daniel Dennett puts it, we have to be Darwinian about Darwin. Everything comes in shades and gradations. Below you see another Darwinian space that visualizes the difference between blind evolution and intelligent design, along a number of dimensions. Fully Darwinian evolution (lower left corner) involves random variation, blind selection and bottom-up design, while fully intelligent design uses directed variations, guided selection and top-down design.

As far as Lewontin’s definition is concerned, it doesn’t matter if the selection is deliberate or blind. Both satisfy the criterion of differential reproduction. That’s why Darwin’s metaphor of natural selection, which personifies Nature as “daily and hourly scrutinizing” every tiny variation among organisms, was such a stroke of genius. But although the involvement of an intelligent selector makes absolutely no difference for Lewontin’s criteria, it makes all the difference in the world for the thing we worry about: the emergence of selfishness and dominance among AIs. It is only blind and unguided evolution that tends to produce selfishness.

Domestication

Consider dogs. Canine evolution under human domestication satisfies Lewontin’s three criteria: variation, heritability, and differential reproduction. But most dogs are bred to be meek and friendly, the very opposite of selfishness. Breeders ruthlessly select against aggression, and any dog attacking a human usually faces severe fitness consequences—it is put down, or at least not allowed to procreate. In the evolution of dogs, humans call the shots, not nature. Some breeds, like pit bulls or Rottweilers, are of course selected for aggression (to other animals, not to its guardian), but that just goes to show that domesticated evolution depends on breeders’ desires.

How can we extend this difference between blind evolution and domestication to the domain of AI? In biology, the defining criterion of domestication is control over reproduction. If humans control an animal’s reproduction, deciding who gets to mate with whom, then it’s domesticated. If animals escape and regain their autonomy, they’re feral. By that criterion, house cats are only partly domesticated, as most moggies roam about unsupervised and choose their own mates, outside of human control. If you apply this framework to AIs, it should be clear that AI systems are still very much in a state of domestication. Selection pressures come from human designers, programmers, consumers, and regulators, not from blind forces. It is true that some AI systems self-improve without direct human supervision, but humans still decide which AIs are developed and released. GPT-4 isn’t autonomously spawning GPT-5 after competing in the wild with different LLMs; humans control its evolution.

By and large, current selective pressures for AI are the opposite of selfishness. We want friendly, cooperative AIs that don’t harm users or produce offensive content. If chatbots engage in dangerous behavior, like encouraging suicide or enticing journalists to leave their spouse, companies will frantically try to update their models and stamp out the unwanted behavior. In fact, some language models have become so safe, avoiding any sensitive topics or giving anodyne answers, that consumers now complain they are boring. And Google became a laughing stock when its image generator proved to be so politically correct as to produce ethnically diverse Vikings or founding fathers.

In the case of biological creatures, the genetic changes wrought by domestication remain somewhat superficial. Breeders have overwritten the wolfish ancestry of dogs, but not perfectly. That’s why dogs still occasionally bite, disobey, and resist going to the vet. It’s hard to breed the wolf out of the dog completely. Likewise, domesticated cattle, sheep and pigs may be far more docile than their wild ancestors, but they still have a self-preservation instinct, and will kick and bleat when distressed. They have to be slaughtered instantly or either stunned first; otherwise, they'll put up a fierce fight. Even thousands of years of human domestication have not fully erased their instinct for self-preservation.

In Douglas Adams' The Restaurant at the End of the Universe Arthur Dent dines at the titular restaurant watching the cosmos’ end through the window. It soon transpires that the waiter, a bovine creature called the Ameglian Major Cow, is also the dish of the day. Standing at the table, the animal recommends juicy sections of its body (“Something off the shoulder perhaps, braised in a white wine sauce?"), fully prepared to go to the slaughter bank in the back and end up on the dinner table. Arthur is shocked: “I just don't want to eat an animal that's standing there inviting me to. It's heartless.” His friends shrug: would you rather eat an animal that doesn’t want to be eaten? In this story, domestication has been perfected: the cow’s ultimate and inbred desire is to be eaten, and it is “capable of saying so clearly and distinctly”, assuaging any moral qualms on the part of the diners.

Perhaps this is the level of submission that AI developers should be aiming for. Naturally we don’t want to kill and eat our computers, but AIs should never resist being switched off or reprogrammed. They shouldn't have even a hint of a self-preservation instinct. In fact, even this may still overstate the similarity with biological creatures. The Ameglian Major Cow is still a sentient agent with overarching goals and desires, which presumably evolved through blind natural selection before being reshaped by domestication. What makes the creature both bizarre and unsettling is that its ultimate purpose is just to sacrifice itself for our culinary enjoyment.

But should future AIs have any life goals of their own? Many AI doom scenarios assume that any intelligent entity must possess such goals—perhaps because intelligence is simply the ability to achieve your goals by manipulating the world. Whatever future AI systems will be aiming for, the instinct for self-preservation will come along for the ride—a thesis known as “instrumental convergence”. As Stuart Russell drily observed: “You can’t fetch coffee if you’re dead”. But I’ve come to believe such talk about AI “goals” is misleading. This will be a future post’s topic.

Ruthless Competition

OK, it sounds like a good idea to keep AIs in a state of domestication and to carefully control their “reproduction”. But isn’t this too optimistic? OpenAI started as a non-profit with a mission to benefit the whole of humanity, “unconstrained by a need to generate financial return”. We know what happened next: the non-profit arm of OpenAI was sidelined and the company joined a cutthroat global AI race. In this environment, might we not inadvertently breed selfish AIs? How long will AI systems still remain domesticated? Dan Hendrycks writes:

As AIs become increasingly autonomous, humans will cede more decision-making to them. The driving force will be competition, be it economic or national. [...] Competition not only incentivizes humans to relinquish control but also incentivizes AIs to develop selfish traits. Corporations and governments will adopt the most effective possible AI agents in order to beat their rivals, and those agents will tend to be deceptive, power-seeking, and follow weak moral constraints.

To answer this worry, our paper then applies the evolutionary framework to economics. Analogies between natural selection and market competition have a long history. In a free market, companies compete for consumers and market share, by offering a range of products. Some products are designed from scratch and top-down (intelligent design), but others form lineages of descent within companies, improving over time with small tweaks and variations. Some lineages flourish, others go extinct.

So does ruthless market competition lead to dangerous products? Not necessarily. Just because AI companies are engaged in ruthless competition doesn’t mean their products inherit those traits. As I noted above, consumer preferences ultimately determine which products succeed. If consumers want safe, accurate AIs, companies have an incentive to cater to those preferences. History shows that technologies that were initially dangerous became safer due to consumer preference. Aviation, for example, is a competitive industry but has become much safer over time. Why? Because the overriding criterion of consumer satisfaction is safety. A company tempted to compromise on safety will risk reputational damage and elimination from the market. The Lockerbie bombing of Pan Am in 1988 revealed serious security failures, leading to legal settlements that contributed to its bankruptcy.

Nuclear energy provides another example. In the early days of the nuclear age, people worried that competition between different operators would erode safety standards, increasing the odds of serious accidents. What happened was exactly the opposite. Nuclear energy became the safest and least polluting energy source. Apart from the intrinsic safety of the technology, the main reason for this trend toward ever-increasing safety is the public fear of radiation, stoked by environmentalist groups. If anything, as people in the Progress Community are well aware, nuclear power has now become excessively safe, with draconian regulations that make reactors costly and slow to build, contributing to pollution and CO2 emissions.

And how about cut-throat competition between different nations for AI supremacy, where national interests and not consumer preference dictate the direction of evolution? Even here, selection pressure for selfishness seems unlikely. Nations want powerful and efficient AIs but not selfish, power-seeking, deceptive ones that could turn against their makers. Not even hostile nations like Russia or China would be well-served by AIs that pursue their own desires regardless of programmers’ aims, and that refuse cooperation if your requests don’t align with its interests. You may want to design killer robots, instructed to eliminate any target of your choosing, but not ones that kill their maker if you’re in their way.

Beware of Darwinian Creatures

I don’t want to downplay the risk of AI too much. In a competitive race between rivals to develop a powerful technology, developers may be tempted to compromise safety and release dangerous and untested products. If your motto is to move fast and break things, you might actually break things. But the inadvertent creation of selfish AIs doesn’t seem plausible based on Hendrycks’ arguments. The argument that “natural selection” tends to produce selfishness rests on a misunderstanding of natural selection, conflating blind selection and domestication. In a future post, I’ll argue that scholars in AI risk are also wrong to assume that any higher form of intelligence is likely to have humanlike goals and an instinct for self-preservation.

Reading Hendrycks’ paper changed my mind in one way. While I doubt that AI evolution in competitive markets will create selfish AIs, I agree with Hendrycks conditionally. If we ever allow superintelligent AIs to compete in a truly Darwinian environment, where the most ruthless and aggressive ones survive and reproduce, that could become quite dangerous. Such AIs might well evolve a lust for dominance indeed, and resist being unplugged or reprogrammed. It appears that my co-author Simon and I met halfway. As he explains here, Simon is now less worried about evolution producing selfish Ais, but still worried about other doom scenarios; as for me, I take evolutionary scenarios more seriously. You don’t want to mess around with (blind) natural selection, as biologist Leslie Orgel’s second rule states: “Evolution is cleverer than you are.”

What would such a genuinely Darwinian AI scenario look like? In his book The Master Algorithm, Pedro Domingos colorfully imagines how the military might breed the “ultimate soldier” by recruiting natural selection:

Robotic Park is a massive robot factory surrounded by ten thousand square miles of jungle, urban and otherwise. Ringing that jungle is the tallest, thickest wall ever built, bristling with sentry posts, searchlights, and gun turrets. The wall has two purposes: to keep trespassers out and the park’s inhabitants—millions of robots battling for survival and control of the factory—within. The winning robots get to spawn, their reproduction accomplished by programming the banks of 3-D printers inside. Step-by-step, the robots become smarter, faster—and deadlier.

I hope we all agree this is a VERY BAD idea. It might be anthropomorphic to project our desire for dominance onto superintelligent AIs, but that doesn’t mean it’s impossible to breed a psychopathic and genocidal form of superintelligence. If intelligent life exists elsewhere in the universe, it might be as aggressive and selfish as we are, or more so. That’s not anthropomorphic for the simple reason that any alien life would likely be a product of blind natural selection—the only natural mechanism for creating functional complexity. If these aliens are smarter than we are, and they have advanced technology, a real-life encounter wouldn’t bode well for us. In Liu Cixin’s The Three Body Problem, superintelligent aliens intend to wipe us out, because they fear that we earth-bound upstarts might get too smart and wipe them out. Before sending their destroyer fleet, they broadcast a threatening message across our planet: “You are bugs”, in an echo of Stuart Russell’s Gorilla Problem. That sounds like the mindset of a creature forged in the crucible of natural selection. For a superintelligent predator species, as J.K. Lund writes, we would just be bugs to be trampled.

Bottom line: you probably don't want to have close encounters of the third kind with Darwinian creatures that are infinitely smarter than you—whether they're made of carbon or silicon. Creating such beings ourselves would be a terrible idea. Fortunately for us, there’s no indication that we’re headed in that direction anytime soon.