If science, like art, is to perform its mission totally and fully, its achievements must enter not only superficially but with their inner meaning: into the consciousness of people.”

— Albert Einstein, in his welcome speech to the 1939 World’s Fair

A row of statues leads to the Perisphere and Trylon (The Atlantic)

In the first chapter of Where is My Flying Car?, J. Storrs Hall makes a counterintuitive observation: “The vision of a bright future world enabled by technology … had been growing in collective imaginations since the turn of the century. It accelerated, rather than slowing, during the Great Depression.”

While the American economy suffered through the worst decade in its history, optimistic storytellers painted visions of a better future grounded in an understanding of the technological capabilities of the era. Hall cites H.G. Wells’ 1935 film Things to Come and the 1939 World’s Fair – with its “Dawn of a New Day” slogan – as two tangible examples of the promised future.

Things to Come

In Things to Come, Wells predicts the impending Great War with spooky prescience. As The New York Times wrote in a 2013 review, “The film begins in 1940, with an unnervingly accurate anticipation of the London Blitz: on Christmas Eve, the citizens of the Art Deco metropolis of Everytown find themselves under attack by waves of bombers from the Continent.”

Between the Depression and the World War, things were undeniably bad for the average person alive at the time, but despite that, the outlook was bright. The 44 million attendees of The World’s Fair entered “The World of Tomorrow” and experienced wonders like air conditioning, personal robots, super-highways, FM radios, fax machines, and the television. The present is bleak – the Fair said – but the future looks bright.

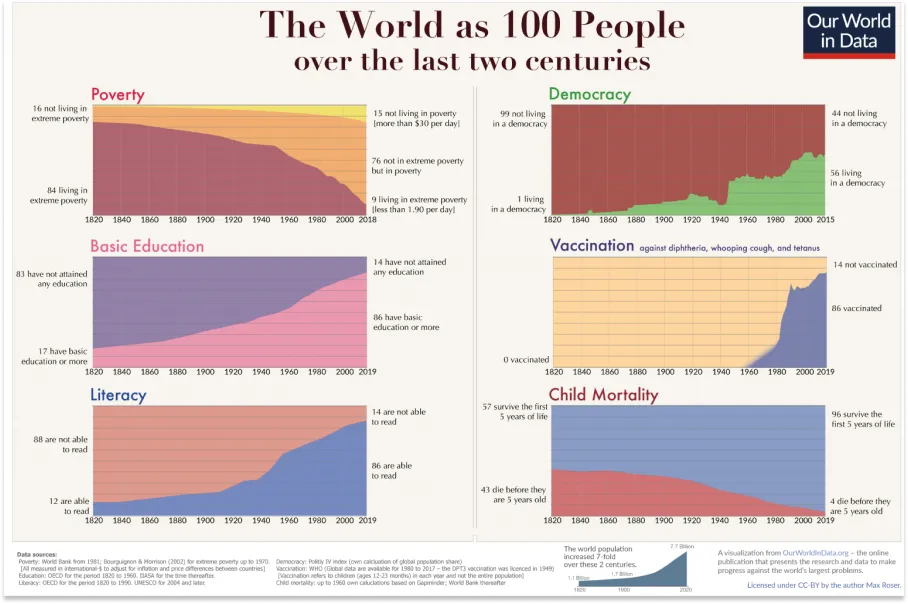

The optimists were right. World War II spurred a wave of technological innovation that worked its way from military applications into peoples’ homes. In Optimism, we wrote about the underappreciated progress humanity has made over the two centuries, but if you zoom in more closely, much of that progress kicked into high gear after World War II.

Our World in Data

Unfortunately, Wells was also correct in his prediction of a future in which technological progress is unwelcome, or as Hall describes it, “it is the Doers attacked by the Do-Nots.” Today, we live in an upside-down version of the 1930s: the present is actually bright, but the future looks bleak.

Every week, we write about new breakthroughs and advances in the Weekly Dose of Optimism. The costs to pull power from the sun, send things into space, and map the human genome are declining precipitously, opening up new avenues for exploration and commercialization. It may take longer than SpaceX suggests, but Mars seems like it’s within reach within our lifetimes. While transformers may not be the architecture that gets us there, AGI, too, seems possible in our lifetimes. Even wars are more autonomous now, saving countless human lives. As Elliot recently tweeted, we can now “hot-wire a patient’s own T cells to attack certain types of tumors.”

https://twitter.com/ElliotHershberg/status/1623049012466286592?s=20

And all of these threads are accelerating and compounding on each other. We recently wrote about Atomic AI, for example, which uses AI to unlock the structure of RNA. Melonfrost, another portfolio company, combines AI, hardware, and synthetic biology to create “the world’s first closed-loop automated evolution system.” CEO Sam Levin told me that the goal is to evolve cells of all types to use biology to “solve climate change and disease and hunger.”

We live in a time that the Golden Age sci-fi storytellers from the 1930s to the 1960s could have only dreamed about, and yet, if you polled the average person on the street, most would tell you that things aren’t looking good. There’s the stat – according to a 2021 Pew Survey, 68% of Americans believe their children will not be better off than they are – but there’s also the vibe.

Space exploration is viewed as a billionaires’ boondoggle. Nuclear power plants are being shut down around the globe. Advances in AI trigger fears of, at best, lost jobs and, at worst, being turned into paper clips. Progress in synthetic biology brings to mind uncontrollable outbreaks and the threat of bioterrorism.

It’s hard to blame people. The buzziest show on TV right now – The Last of Us – takes place in a world where, per NPR: “climate change has fueled the rise of a new pathogen, which sweeps around the globe infecting humans, turning them into zombies and controlling their brains.”

This is your brain on climate change.

It’s also just plain difficult to keep up with the dizzying pace of progress, even for those of us who try to do it professionally, especially given the polarization that builds up around anything interesting. We can’t expect people to read every paper claiming a new breakthrough in AI. People are told that mRNA vaccines are a miracle, and then that they’re evil killers. Every time we write something positive about solar or nuclear, we get comments about the drawbacks of each and are told that the other is actually better. Elon Musk’s Twitter antics make for more compelling drama than the successful test of his other company’s Super Heavy Booster.

https://twitter.com/SpaceX/status/1624150738447536128?s=20

There’s a triple-whammy afoot: everything is more complex and faster-moving than it was from the 1930s through the 1960s and the world is more decentralized. People get their information from a billion different sources, barely catching snippets. Doomerish stories are more likely to cut through the noise than nuanced ones. “If it bleeds, it leads,” minus the fact-checking and journalistic rigor.

Fortunately, humans long ago devised a tool to help us make sense of a confusing world: narrative.

We need knowledgeable people to tell Good Stories, to weave together all of the threads of the current state-of-the-art into compelling narratives that help clarify the future. Importantly, they need to help people understand the impact – good and bad, not just bad – that new technologies might have on their lives. As Einstein said, the achievements of science (and technology) “must enter not only superficially but with their inner meaning: into the consciousness of people.” Research papers don’t worm into the consciousness of the people. Stories do.

In The Purpose of Technology, Balaji puts the onus back on the technologists themselves.

We need to take time out of our busy days to make the case, repeatedly and with high production values, that technological progress is the most important thing we can do for broad-based prosperity and economic growth, and for life itself.

That starts with testing, drugs, treatments, and vaccines for COVID-19. But it goes far beyond that. Put another way: we may not get life extension or the whole suite of transhumanist technologies (brain-machine interfaces, stem cells, CRISPR gene therapy, and more) unless you, personally, evangelize them online. Not just tweets, but articles. Not just articles, but videos. Not just videos, but feature films. And not just a few films, but an entire Netflix original library's worth, a parallel tech media ecosystem full of inspirational content for technological progressives. A lifetime's worth of content that makes the case for immutable money, infinite frontier, artificial intelligence, and eternal life.

Optimistic storytelling can lift people out of their current circumstances and give them hope for the future. If it worked during the Great Depression, it can work today. As importantly, it can help rally people behind Good Quests, remove barriers for those working to make a better future, and inspire the next generation to dream bigger than their parents ever could.

Today, we’ll focus on two forms of storytelling: Science Fiction and Spectacle.

Science fiction speaks to inventors, engineers, and scientists – the people building the future. Spectacles help people experience what those futures might feel like for them.

Sci-Fi: Making the Frontier Not Boring

It’s hard to write a piece about optimistic storytelling without discussing the genre that perfectly encapsulates it: science fiction. This genre is crucial to civilizational progress because invention needs inspiration, and inspiration often comes from stories.

At its best, optimistic sci-fi makes people believe that the future is worth it and possible to achieve. We had that in the 1930s-60s when many consumed content from the Golden Age of science fiction, from works by Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, and Robert Heinlein to Hollywood staples such as The Jetsons, Star Trek, and 2001: A Space Odyssey. These positive portrayals of technology were a force for good against the backdrop of the Apollo Missions, the Atomic Age, the Computing Revolution, and other tech trends. The best part: they inspired kids to become engineers, astrophysicists, and future-builders.

In a 2011 WIRED essay, Innovation Starvation, sci-fi author Neil Stephenson recounts attending that year’s Future Tense conference and bemoaning our seeming inability to get big stuff done. The audience pushed back, believing, like we do, that science fiction can play a role in fixing the problem. Stephenson boiled what he heard down to two theories:

“The Inspiration Theory. [Science fiction] inspires people to choose science and engineering as careers. This much is undoubtedly true, and somewhat obvious.

The Hieroglyph Theory. Good [Science Fiction] supplies a plausible, fully thought-out picture of an alternate reality in which some sort of compelling innovation has taken place. A good [science fiction] universe has a coherence and internal logic that makes sense to scientists and engineers. Examples include Isaac Asimov’s robots, Robert Heinlein’s rocket ships, and William Gibson’s cyberspace. As Jim Karkanias of Microsoft Research puts it, such icons serve as hieroglyphs — simple, recognizable symbols on whose significance everyone agrees.”

As science and technology have become more complex, according to Stephenson, each individual researcher and engineer is left responsible for a thinner and thinner slice of the overall project. In Centralization vs. Decentralization: Two Centuries of Authority in Design, Smári McCarthy wrote of workers during the Industrial Revolution, “From the craftsmen they were, people were reduced to mere automata to which meaningless and repetitive tasks were assigned – so as to ensure the production and manufacturing of goods in the context of large industrial facilities.” Stephenson identifies the same issue two centuries later, and a layer of abstraction higher: even those designing the machines have been reduced to mere automata.

That’s where practical techno-optimistic sci-fi comes in:

The fondness that many such people have for SF [science fiction] reflects, in part, the usefulness of an over-arching narrative that supplies them and their colleagues with a shared vision. Coordinating their efforts through a command-and-control management system is a little like trying to run a modern economy out of a Politburo. Letting them work toward an agreed-on goal is something more like a free and largely self-coordinated market of ideas.

Stephenson’s take challenges writers, poets, filmmakers, and other creatives to start pulling their weight and supplying big visions that help the doers self-coordinate. In the past, the golden collaboration between creatives and creators yielded Good Quests that addressed generational problems and advanced our understanding of the universe.

Take the advent of the space shuttle. Sci-fi authors of the 1900s devised countless methods for space travel, some of the most popular ones being:

Small vehicles and payloads launched by microwave-heated hydrogen fuel

Ground-based laser pulses to blast propellant from a vehicle (which was championed by Arthur Kantrowitz and Freeman Dyson of Dyson Sphere fame)

Tethers, or long ropes that orbit Earth with which payloads can be hooked onto and hauled to space

Traditional rockets

All of these possible sci-fi futures were attempted! Microwave propulsion, laser propulsion, and space tethers have all been endeavored by academia and even commercialized startups. Fast forward to today, and we have chemical and nuclear propulsion, kinetic energy launchers, 3-D printed rockets, and reusable rockets (thanks Elon). Sci-fi creatives planted the vision, and engineers executed it.

One of my favorite examples is from a tweet by Imran Chaudhri, who was Apple’s Director of Design from 1996 to 2016.

https://twitter.com/imranchaudhri/status/1092194839540584449

Chaudhri designed the software and hardware behind almost every major Apple product during his stint—including the iPhone. He says in that tweet that the invention of the iPhone 1 was directly inspired by the original Mac, Blade Runner, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Sony Walkman, the Concorde, Arthur C. Clarke, and more. This again shows how invention and technological progress take inspiration from sci-fi works, optimistic stories, historical stories, past inventions, renegade artists, crazy people, ambitious people, and everything else. All of that came together to inspire the most important product of the 21st century. That’s the power of storytelling.

William Gibson, author of the seminal sci-fi work Neuromancer, coined the phrase, “The future is here—it’s just not evenly distributed.” The future he speaks of is crafted by creatives and invented by moonshots startups & labs worldwide. Narratives are everywhere—they just need to be vitalized. Sci-fi is a way of doing just that: inspiring people, predicting possibilities, and considering nth-order consequences.

Spectacle: An American Enlightenment

But let’s be honest. There aren’t that many of us nerds who read sci-fi. A quick perusal of Amazon and some napkin math shows that about 3% as many people read 2022’s Hugo Award winner, Akrkady Martine’s excellent A Desolation Called Peace, as read BookTok sensation Colleen Hoover’s It Ends With Us.

Amazon

We’d love to see a world in which great sci-fi takes off on TikTok the same way that young adult romance does, and we believe that techno-optimistic stories should be told in all formats, but for the time being, the role of science fiction is to inspire the builders. That’s half the battle.

The other half is helping those outside of tech experience the impact that new technologies might have on their lives first-hand. And for that, nothing beats a good spectacle. To whit, on Sunday, roughly 200 million people tuned in to watch the Super Bowl, as much for the pageantry, commercials, and Halftime Show as for the football game itself.

Spectacle can capture the public imagination, and done right, advances in technology can make excellent spectacle fodder.

As the epitome of optimistic narrative-building spectacle, the 1939 New York World’s Fair was a turning point in global futurism, as it was the first Expo to (literally) look toward "The World of Tomorrow."

Its slogan: "Dawn of a New Day.”

For two years, 44 million people — including people affected by the Great Depression — experienced new scientific and technological frontiers for the first time. Watch this newsreel from 1939:

The exhibition promoted the harmony of countries and governance worldwide; the sharing of food, dance, and culture; the revival of heroic, regal art; and the breakthrough entrepreneurship of the time. It emphasized — through amusement, entertainment, exhibitions, and experiences — that science is for all, that the future can be built, and that we can collectively be amazing.

The 1939 Fair was based on the concept of “X of Tomorrow”: technology, science, transportation, communication, food, government, community interests, amusement, etc.

The Fair celebrated “Tomorrow” by showcasing the futuristic appliances available “Today.” Attendees saw newly adopted innovations like television, mass electric power, and cars next to longer-term possibilities such as personal robotics, space travel, and more.

Yet, it wasn’t just a science fair. It was a means to show how progress would shape daily life. Companies showed off their newest toys and their wildest ideas side-by-side:

- General Motors showed off a model city designed for cars with super-highways from coast to coast and no red lights in the Transportation Zone.

- Ford also displayed some of its newest vehicle designs in the Transportation Zone.

- General Electric introduced the world to the fluorescent light bulb and equipped an auditorium with a new invention: air conditioning.

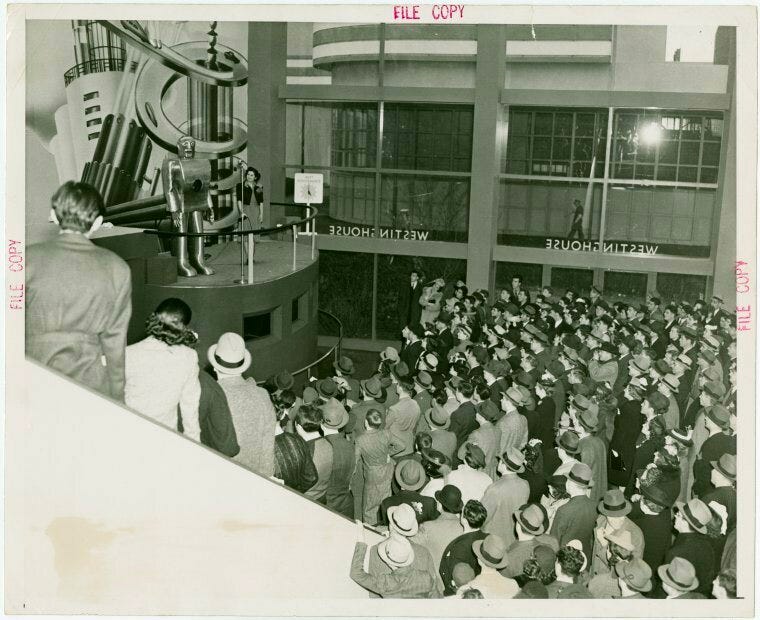

- Westinghouse unveiled the seven-foot-tall “Elektro the Moto-Man,” a personal robot that could talk and perform tasks for regular consumers.

- In the Communications Zone, AT&T showed off a mechanized, synthetic voice assistant that could speak to fairgoers.

- IBM unveiled new devices of its own, such as the electric typewriter and an electric calculator.

- RCA showed FM radio, the fax machine, and the television. Their technology was used to televise Fair events and even made President Franklin Delano Roosevelt the first president to be televised.

- Heinz laid the blueprint for baby food.

Many of these inventions seem old hat now, others are just arriving today, and we’re still waiting for some 84 years later, a testament to the exhibitors' mix of can-do spirit and optimism.

The General Motors Pavilion, within which was Futurama, a model city that onlookers viewed from above

The Fair embodied a long-lost American ideal: the unconditional belief that science and technology fuel economic prosperity and personal freedom. Caught between the Great Depression and World War II, the Fair was the antidote to misery and chaos. It gave people hope.

The New York World’s Fair Committee intended the event to not be far-future speculation but rather a realistic, definite-optimistic vision: “The main purpose of the New York World Fair of 1939 [was] to show the tools of today with which America is preparing to build a better world of tomorrow.” It provided a search for a “useable Future (with a capital ‘F’)” and of hope, possibility, and dynamism in the face of catastrophe.

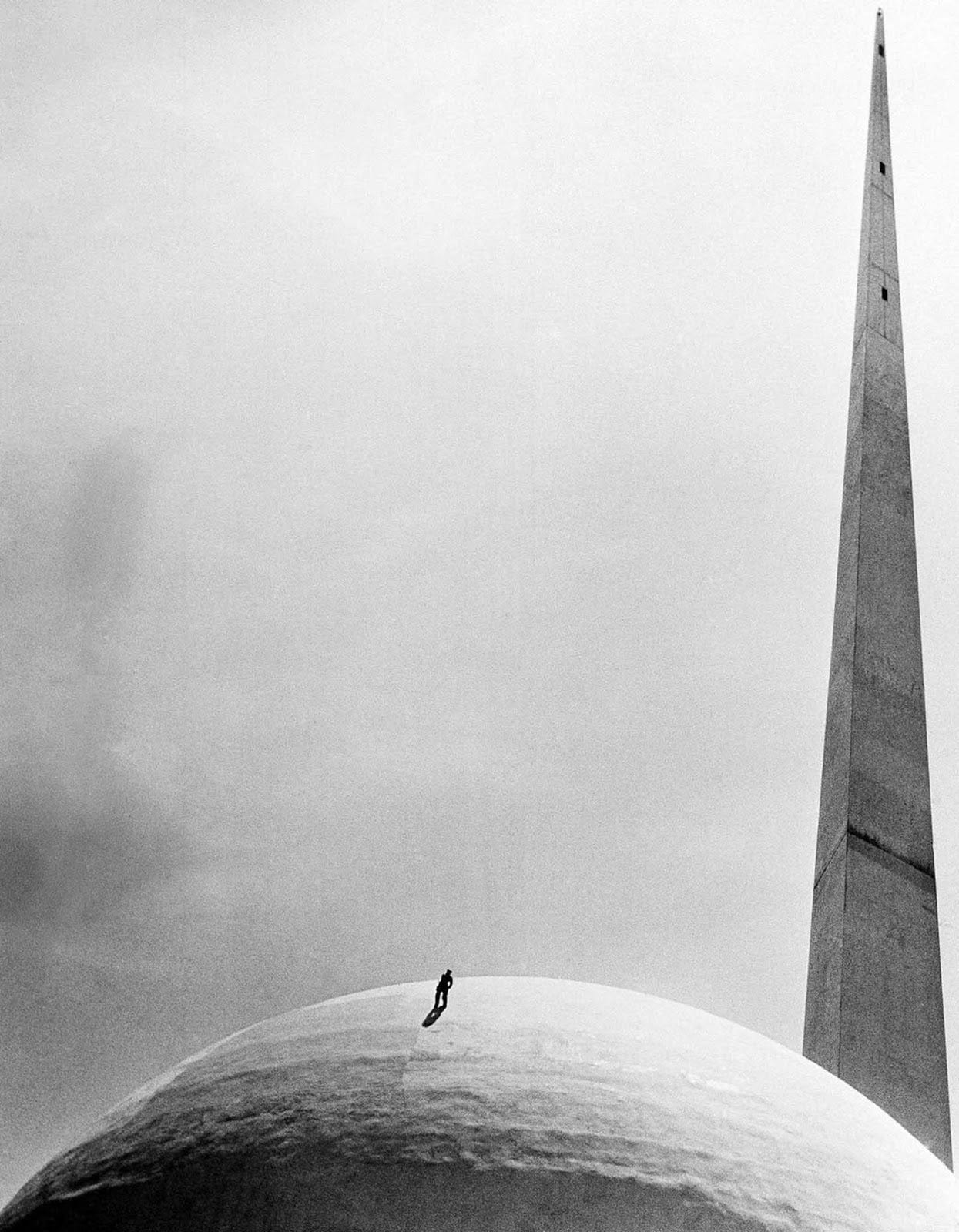

The “usable Future” piece indisputably left an enduring cultural and spiritual legacy. This specific World’s Fair combined a future-facing ideological construct, trade show, League of Nations, amusement park, and utopian community to uphold the prophecy that an abundant, free society can be achieved through technology. Even the social norms, art, and architecture were stylistically advanced and unlike anything of the time, such as the Trylon and Perisphere.

Man working on top of the Perisphere (Source)

The 1930s through 1960s were a Golden Age of World’s Fairs, too. The USA hosted other major World’s Fair expositions: the 1933 Chicago Century of Progress Exposition, the 1939 San Francisco Golden Gate International Exposition, and the 1962 Seattle Century 21 Exposition. America ended its run of hosting such events with a bang: the infamous 1964 New York World's Fair.

As a collaboration between Robert Moses (yes, the Power Broker) and Walt Disney, the 1964 World’s Fair embodied “Peace Through Understanding" and dedicated itself to "Man's Achievement on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe.” This Fair reintroduced consumers to some of the era’s most impactful inventions: computers with keyboards, teletype machines, telephone modems, Saturn V’s engines, Gemini spacecraft, lunar rovers, satellites, videoconferencing, animatronics, futuristic homes, undersea hotels, electric cities, nuclear power plants, and color TV. Corporations again took the lead on this narrative with grandiose exhibits such as:

- General Motors’ Futurama displayed dioramas of a possible near-future society.

- DuPont presented The Wonderful World of Chemistry.

- Sinclair Oil Corporation sponsored Dinoland, featuring life-sized dinosaur replicas.

- Bell System constructed the Ride of Communications.

- General Electric sponsored the Carousel of Progress, where audience members revolved around an audio-animatronic presentation of the progress of electricity in the home.

- Disney laid the foundation of the entire Fair and specifically designed Pepsi’s “It's a Small World,” General Electric's Progresslan, Ford’s Magic Skyway, and the first audio-animatronic presentation ever in Illinois Pavilion’s “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln.”

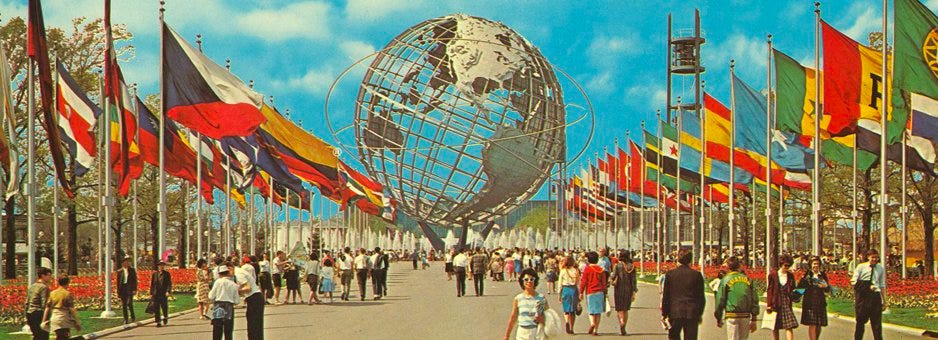

The Unisphere at the 1964 World’s Fair

The Fairs were moments when the world rejoiced in a collective appreciation of science, technology, and global unity. From a macro view, America saw so much progress during the main stint of the Fairs (1851 - 1964). Despite the crazy backdrop of global events, people saw their day-to-day lives rapidly improving (think about the home in the 1890s versus the 1960s). Food, transportation, cities, medicines, electronics, energy, everything. The best part: everyone felt and saw these advances. Things were booming. You didn’t have to look very hard to see the future improving.

It’s that exact narrative that made the Fairs so special. People realized that we are capable of so much more, and we can achieve it. The 1933 Chicago and 1939 New York fairs pulled America, culturally and emotionally, out of the Great Depression; the 1964 Fair spread harmony in the globalized Space Age. Better yet, they literally brought science to people’s doorsteps with Elektro, Westinghouse’s voice-controlled personal robot that could walk, talk, and smoke a cigarette.

Elektro’s unveiling at the Westinghouse Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair

Westinghouse toured “him” around the country to get people excited about the potential to have a robot in their house. Check it out here:

The last World’s Fair in the United States took place, ironically, in 1984, that dystopian year foretold in science fiction. Facing competition from a technology previewed at the 1939 World’s Fair – the television – and from the architect of the 1964 World’s Fair – Disney’s EPCOT – the 1984 Louisiana World Exposition ended in bankruptcy. But a lot has happened since 1984, and the future looks brighter now than it did then. It’s time for a new World’s Fair.

To that end, we’re particularly excited about our friend Cam Wiese’s World’s Fair Co.

World’s Fair Co.

By the end of the decade, Cam & Co. plan to “open the gates to the next great World’s Fair,” showcasing advances across a number of the categories we write about here in Not Boring.

World’s Fair Co. x Invisible Creatures

Planning a whole World’s Fair is a decade-long journey, but in the interim, there are opportunities to draw inspiration from the Fairs to create experiences around new technologies that let people feel the magic for themselves and picture how their life might change for the better. It’s not a coincidence that art kicked off the AI renaissance and that GPT reached 100 million users faster than any other company when OpenAI put it behind a familiar chat interface. The technology moved from research paper to spectacle.

Founders, leaders, and other pioneers should take the helm just as they did in the Fairs. We all have a moral imperative to make science fun.

I Have Seen the Future

Pins with the above phrase were given to fairgoers in the 1939 Fair. It became a status symbol for many.

Narratives are a double-edged sword. They can instill hope or fear. And the fear side is sharper.

Think about the narratives that have broken through in the past few months. War. Elon’s Twitter. The FTX Fraud. The Impending Recession. The Chinese Spy Balloon. Even Mr. Beast paying to cure blindness in 1,000 people made people angry.

https://twitter.com/MrBeast/status/1620195967008907264

These are all important stories, and I’m not suggesting that they shouldn’t get coverage. They should. Skepticism is an important part of pragmatic optimism, and good journalists play an important role. But the balance is off. The Good Stories aren’t being told as loudly or as compellingly as they could be.

In 2022 alone, we saw some crazy breakthroughs that are already impacting people’s lives: the FDA approved 37 new drugs, bionic eyes restored blindness, cancer death rates decreased, Al-powered protein predictions were validated, malaria vaccine became twice as effective, a girl’s cancer was cured with base editing, multiple rare disease advances were made, life was created without egg, sperm, or a womb, gene-editing got safer and more precise, gene-therapy-based sickle cell anemia cure came about, spinal implants helped paralyzed people walk and swim, scientists achieved nuclear fusion ignition, states green-lighted medical use of psilocybin, wastewater tracking systems detected outbreaks in cities, perovskite-based solar cells broke the 30% efficiency barrier, new ways to prevent LDL (the leading cause of heart attacks & strokes) went mainstream, large language models saw massive adoption, the James Webb Telescope revolutionized astronomy, an asteroid was redirected, and more. So. Much. More.

Sitting in the middle of all of this, trying desperately to keep up with the frenzied pace of innovation, it’s hard not to see how the future will be better than the present, and that the present is better than the past.

But the stories we tell, the ones that people are listening to, paint a different picture. They ask, “What could go wrong?” instead of “How can we work together to make this go right?”

Stephenson had thoughts on why this is, too. Explaining why “Speaking broadly, the techno-optimism of the Golden Age of SF has given way to fiction written in a generally darker, more skeptical and ambiguous tone,” he wrote:

Believing we have all the technology we’ll ever need, we seek to draw attention to its destructive side effects. This seems foolish now that we find ourselves saddled with technologies like Japan’s ramshackle 1960s-vintage reactors at Fukushima when we have the possibility of clean nuclear fusion on the horizon. The imperative to develop new technologies and implement them on a heroic scale no longer seems like the childish preoccupation of a few nerds with slide rules. It’s the only way for the human race to escape from its current predicaments. Too bad we’ve forgotten how to do it.

That essay is from 2011, but a dozen years later, it seems as though we’ve remembered how to develop new technologies and implement them on a heroic scale. The narrative just hasn’t caught up.

The other day, tongue in cheek, Packy tweeted a poll asking what finally got the aliens interested enough in humans to reveal themselves:

https://twitter.com/packyM/status/1624549206202392576?s=20

Fusion, AGI, and interplanetary travel are three of the most common themes in sci-fi from any era. All three appear in Asimov’s The Last Question. They’re humanity-altering technologies. In the past three months, during a period of doom and gloom and supposed stagnation, we’ve taken meaningful steps closer to achieving all three. And the implications are going to be confusing as hell to work through.

That’s where stories come in.

Those who understand today’s technology well enough to envision worlds born of its extrapolations should do so. Write sci-fi, make movies, create art, build monuments, bring back World’s Fairs.

We should return to the days of celebrating big achievements as they elicit feelings of pride in the public towards doing impactful things. We should build more monuments, new wonders of the world, and massive art installations. Statues of true heroes, structures like The Colosseum and the Taj Mahal, museums full of art ahead of their time. Even amusement parks like Disney’s EPCOT (“Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow”).

It’s not about blindly celebrating tech founders. It is possible to be both optimistic and cautious.

And, it’s not about being “nicer” to tech. Stories are simply a way to compress information and help people grok the positives and wrestle with the negatives of everything going on. Negative stories have a natural advantage; putting more effort into telling Good Stories would help balance the scales. The impact of this cultural change would be immense.

Humans need narratives to make sense of things. Stories help us understand what to do, what everyone else is doing, and how to do it. They ask, what is possible? What needs to be done? What Can You Do For Your Country? They are motivational, guiding, and inspiring. They are pure magic. They make the pursuit of the impossible attractive and attainable.

There’s this great quote from Karen Armstrong in The Great Transformation: “Unless there is some kind of spiritual revolution that can keep abreast of our technological genius, it is unlikely that we will save our planet. A purely rational education will not suffice.”

I’d amend it in a couple of ways.

Unless there is some kind of narrative revolution that can keep abreast of our technological genius, it is unlikely that we will reach our full, amazing potential. A purely rational education will not suffice.

We need better sci-fi to guide builders who want to create a magnificent future, and dazzling spectacles to let people picture themselves in it.

It’s time to tell Good Stories again.

When I read this I felt a need to shout "YES!!" to all of this. In the past couple of weeks, as I've talked to people in the broader progress studies community I heard a lot of personal stories, and many of them included either influential stories (often Science Fiction books, but sometimes also historical tales of human ingenuity and invention or movies) or experiences in spaces that made possibilities real (like Disney Epcot or even museums with inspirational themes).

I'd love to hear from people in this community how these types of experiences played into their journey of being interested in scientific, industrial, technological, and human progress.

The inventor of the cell phone was inspired by the TOS communicator. There's a lot of examples of this in engineering, I think.

I think you hit the mark with a lot of us having an underlying belief in progress independent of progress studies, and that a lot of that excitement/belief was inspired by media or culture. When I worked in sales, one of the team mottos we had was that people make decisions with emotions first, and then rationalize them later. Regardless of whether that's how people "should" make decisions, I think it's reasonably accurate. Creating art and media that celebrates progress, and having audiences have an emotional reaction to that media, is a great first step in getting more people invested in creating real-world progress. Disney and the other World's Fair promoters certainly understood this, and on some level, I think everybody who pines for a Mid-Century World's Fair does too.

Adam Ozimek had a twitter thread about a year ago where people pitched ideas for "progress studies" television shows - I wonder if anything happened to that. I stand by my pitch for a campy, positive, and fun 1632 mini-series.

I'm also very curious on what we, as a progress community, can contribute to the telling of more good, inspiring stories. If you have thoughts, please comment or get in touch: heike@therootsofprogress.org.

Excellent description of how stories play a critical role. I'm interested in whether the same sorts of stories could be updated and played again, or whether it has just become harder to share these kinds of stories. In the UK, in 1951, there was the Festival of Britain, which was similar to other events of the time: showing how the future could be great. It was at the newly built Southbank Centre. Such events require lots of public sector funding and, particularly to hold frequently, bi-partisan commitment. It seems like this is a prerequisite for national-level storytelling? Today, we have global ExPos, but they are every five years and garner little attention (Dubai 2020, Japan 2025). I would be curious to know what people think it takes to tell these stories. Good piece; really enjoyed reading & have shared with my team (who are planning an Expo just like this!)