Ever since covid forked our collective timeline, the urban doom loop has been a consistent feature of The Discourse™. Some of that has come from urbanist commentators. Some of it was picked up by online culture warriors trying to dunk on “democrat run cities”.

But for all the coverage about political mismanagement and bureaucratic incompetence, there are underlying mechanisms that have prevented cities across the U.S. from quickly adapting to the post-covid world.

For the purposes of this conversation, I’m going to focus on San Francisco. Partly because San Francisco is what I'm most familiar with, but also because lessons from SF’s experience have applicability to other cities as well.

Explaining the Doom Loop

Before 2020, downtown San Francisco (on a weekday) was packed. Something like 470,000 people used to commute into the city for work every day. Then covid + remote work happened and that world disappeared.

Tech companies — the main drivers of downtown employment — went remote and workers stopped coming into the office. Many employees even relocated out of the region entirely (especially in the beginning when they were eager to take Bay Area salaries to Boise or Colorado Springs).

We might call that the doom part. What followed next was the loop bit.

As white collar work left, the service sector dried up as well; without a critical mass of tech workers, the downtown market for $30 shawarma imploded. And as demand for commercial space — retail, restaurant, and office — evaporated, commercial real estate got put over a barrel.

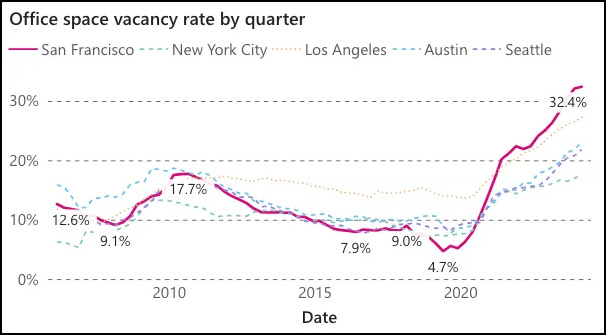

In the heady days of 2019, commercial vacancy rates fell to 4.7%. Today, they’re consistently above 30%.

Obviously, this isn’t great for commercial landlords, but it’s also been bad for municipal finances. San Francisco relied heavily on taxing commercial leases and property sales, two wells that have all but dried up at this point.

Bigger picture, the city’s tax structure assumed the world would continue on as it had since 2010. That train has jumped its tracks and private sector problems have cascaded into public sector budget shortfalls.

Contra Econ 101

For those of us with just the wrong amount of economics education, this may be the part of the story where something feels a little off.

It’s been several years since remote work started in earnest and the dreams of reverting back to the pre-pandemic status quo are pretty well dashed. Why hasn’t the price for commercial space just fallen to the point that supply and demand equilibrate?

Well, the short answer is that sometimes prices are sticky. But why these particular prices are so sticky needs a little unpacking.

For starters, many commercial landlords use non-trivial amounts of debt for financing. The value of the asset for which they took out loans in the first place — their buildings — is based on the expected future value of revenue. More simply, a building's value is based on how much it’s supposed to make from its leases.

If a landlord significantly marks down leases, it needs to update its prospectus and mark down the value of the asset as a whole. That could trigger investors to call back their capital and force the landlord to sell their now less valuable building at a loss. Given that reality, many landlords have been trying to just wait out the dry season.

Even landlords who own their buildings outright are still incentivized to keep a property vacant rather than reduce its rent.

Most commercial leases last 5-10 years. As a consequence, many landlords have been holding out for fear of getting locked into a lease with favorable pricing for tenants. They can’t afford to miss out on a potential, meaningful return to office.

To be clear, this isn’t landlords being stingy about offering minor concessions or lowering rents a couple percentage points off of previous highs. Last year, we saw a single commercial real estate transaction where an office building sold at an 80% discount relative to its pre-pandemic valuation. Now, property valuation and leases don’t necessarily track 1:1, but that should give us a sense of the magnitude for how much less valuable San Francisco’s downtown commercial real estate has become.

If not offices, why not housing?

That explains why commercial space hasn’t just been marked down to 1990’s levels and ushered in a new golden age of artist collectives and downtown co-ops. But it doesn’t explain why these spaces haven’t been repurposed for something that’s still definitely undersupplied in San Francisco — housing.

The answer, like the answer to many things in life, is complicated.

First off, we have code requirements. Building codes specify all manner of design requirements for buildings. Different classes of buildings (i.e. commercial versus residential) have very different requirements.

For example, San Francisco’s building codes require a certain amount of natural lighting for each unit; you can’t subdivide a large floor of an office building and create units that don’t have an exterior wall with a window.

Similarly, office buildings are usually built with centralized plumbing that runs up through the middle column in the center of the structure. Converting entire floors to residential would require redoing the plumbing to serve each individual unit (instead of just the centralized bathrooms in an office).

For these and a thousand other reasons, it’s complicated and costly to retrofit office space for residential use. Although the city has created tax incentives to encourage conversion, it’s still not penciling for most developers most of the time.

What would a more flexible world look like?

At this point, it might be easy to read the problem as onerous regulation impeding progress. And, while that’s kinda true, it’s not true in the way we might think.

On the whole, building codes are fine. They mostly don’t impede housing production and give us baseline standards for safety.1 In my view, the original sin lies firmly with zoning.

If building codes tell you how you have to build something, zoning tells you what you’re allowed to build in the first place.

On one level, San Francisco’s zoning hasn’t allowed much housing and over planned for office space in downtown (especially for the world we find ourselves in today).

There’s a deeper problem, though. Inherent in zoning (as it’s employed in the U.S.) is the assumption that different activities should take place in different places and never the twain shall meet.

That’s bad.

Japanese style zoning famously doesn’t care if the structure attached to your house is being used as a garage, coffee shop, or bookstore. Even the French are less uptight about separation of use; in Paris — a city that some have said feels like a museum to former glory2 — you can have a dentist’s office across the hallway from an apartment.

In a world where developers aren’t constrained by zoning in the ways they are today, we might have gotten construction with more flexibility baked in. Buildings could still have been built as office space, but with design affordances to facilitate pivoting uses when/if the need arose.

That’s not to say that flipping a switch on zoning today solves our current problems. It is, however, a big part of why repurposing the built environment is such a slow and painful process.

Coda

The world changed and everything about how we constructed, financed, and regulated the built environment in downtown San Francisco means it’s really, really hard to adapt to the new reality.

This didn’t have to be the case.

Cities are platforms for collective prosperity and, in a perfect world, the way they’re shaped and how they work is a reflection of our wants and needs. But the world can change in sudden, dramatic ways and when that happens what we need from our cities changes as well. Whether or not cities are able to meet those changing needs is downstream of the institutions we use to shape them in the first place.

Just like cities, institutions are things we build. Instead of aggregations of brick, though, they’re constructs made up of human choices. We can choose different institutions and we can choose to build cities that are better prepared to meet tomorrow, whatever else may come our way.