This newsletter, Ziggurat, aims to show ways to make the world work better. We can each do practical things on that front, starting today. We can do them without getting into party politics. And we can do them in a popular, friendly, consensus-building way. But it takes a little knowledge and practice. I will suggest ideas that might help. They come from existing research, little known except to specialists. This field is less precise than writing software, because people are not computers.

It’s more like farming: some things are much more likely to work than others, and there are many useful tricks. If a farmer does not learn what and when to plant in a given soil and climate, they will not be a farmer for long. And discovering a new technique may improve the lives of millions.

When we have learned these ideas, I hope we will improve and build on them together.

Grand plans to fix the world mainly fail. Often they backfire. But sometimes – those rare, precious times when they are well designed and implemented, and with a little bit of luck – they can transform a place, or even a country.

Today we look at building more homes in Manhattan, retirement in the US, and Britain’s National Health Service. Two reforms happened by building coalitions. One prevailed by starting small, and letting people vote with their feet.

None is perfect; each is limited. You may dislike their aims or methods. I think there are better, less controversial ways to improve the world. They are here to show the techniques used to get change, not the particular goals of each. They succeeded in getting the change they wanted. They give us hope of succeeding too.

1. Housing in Manhattan

Manhattan has among the most expensive housing on Earth. Many times more people want to live in Manhattan than the island has homes for. The city has a wealth of high-paying job opportunities, with cultural activities to match, attracting residents from all over the world.

Manhattan does build more homes, but in small numbers. That is partly due to technical and economic limits. But recent ‘supertall’ towers, like 432 Park Avenue above, show how much more Manhattan could build if it wanted. The slowness mainly stems from the suffocating shortage of places where more homes are allowed to be added. The main reason why people don't build far more in Manhattan is that they mainly aren't allowed to. And legal limits on what can be built have become tighter over time. Today it would be illegal to build 40% of the current buildings in Manhattan.

And the main reason for those legal limits is politics. People often don’t like things being built near them. And the wealthier they are, the more resources they will throw at stopping more building, and the more influential those efforts are likely to be. The backlash against victories of pro-housing campaigners has become so fierce that there is now a petition to amend the constitution of the state of California to stop the state from forcing towns and cities to allow more homes. But the shortage of homes in places like New York City, San Francisco and London aggravates a vast array of problems, in ways not generally realized.

Some remarkable wins for pro-building forces have involved Transferable Development Rights or ‘TDRs’ – often known as ‘air rights’. Essentially, they allow the rights to develop in the empty space above one existing building to be sold to the owner of another parcel of land, allowing that second owner to instead build higher on their own parcel than would otherwise be permitted. One early advocate of a tradeable air rights system was a professor at the University of Illinois, John Costonis. He wanted to offer them as bribes to landowners in Chicago, to agree to preserve landmark buildings, when the City had limited other powers and was short of money.

Air rights can beat resistance to development by assembling a political coalition including the sellers of TDRs, the buyers of TDRs, and the other winners from the TDR scheme. Manhattan has a series of Special Districts that are able to use TDRs. The big Special Districts enabled massive new developments that, otherwise, would likely have been politically impossible.

Mayor de Blasio successfully passed an upzoning reform in 2017. It was designed as a bundle of benefits for vocal interest groups. For example, he promised the City’s Catholic Cardinal, Timothy Dolan, more practical options for selling his cathedral’s 1.1 million square feet of air rights. Dolan then spent $320,000 on lobbyists supporting de Blasio’s plan and arranged for leaflets promoting it to be handed out at Pope Francis’s visit to Madison Square Garden.

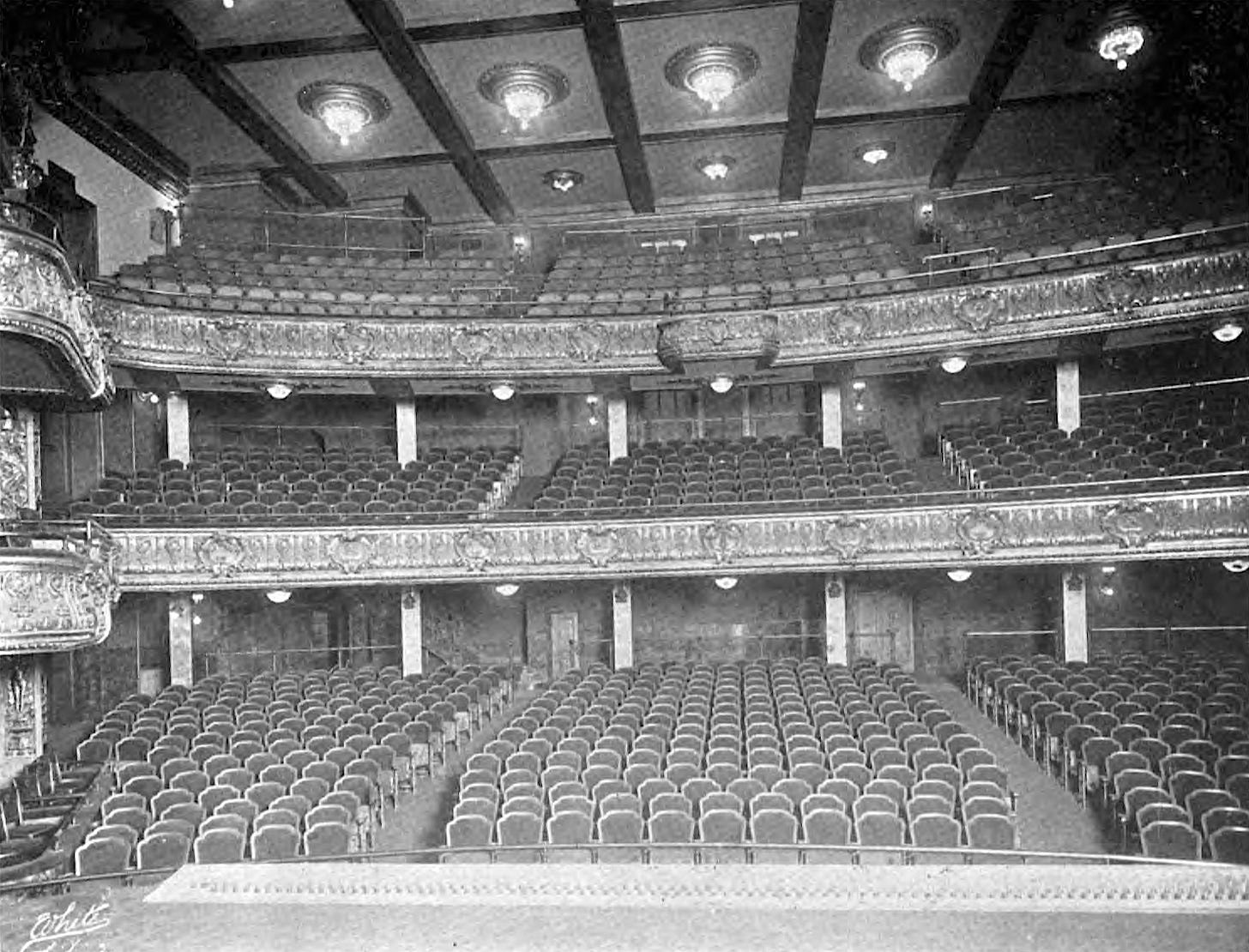

To allow more development while protecting existing theater buildings and their role as theaters, the City created the Special Theater Subdistrict. The scheme gives owners of dozens of Midtown theaters immensely valuable air rights which may only be transferred if the theater is certified as operationally sound and its owner undertakes to continue to use it as a legitimate theater.

The genius of the scheme is that it brought into the coalition an enormous constituency of vocal and well-connected supporters who love watching performances on Broadway and want to preserve the variety of entertainment. They provided powerful backing to theater owners, performers, and the other employees who benefit from continued theater operation.

Since then, over 450,000 square feet of air rights have been transferred. Of course, the neighbors of the resulting new developments were fiercely opposed to the scheme, but their complaints fell on deaf ears. Their lawsuit under the State Environmental Quality Review Act was rejected by the appeal court. One neighbor group ruefully acknowledged that the new coalition created by the Mayor had immunized the reform from political attack. Too many people had an interest in the reform succeeding.

The same technique unlocked political obstacles to transforming the area around Manhattan’s High Line. It allowed owners of property beneath the railway to transfer some of their unused upward development rights to other sites in the district where development was desired.

Transferable Development Rights are a clever kind of benefit. The city could give cash, but it would have to raise taxes, and that would be unpopular. The main visible costs of TDRs are to those who live near the resulting new development. But if the city defines a large area where a small amount of TDRs can be used for new building, it is unlikely to affect any particular current resident in that area. So the potential impacts may be too uncertain and unlikely for strong organized opposition. And there will be only an imperceptible impact on the thousands of landlords across the city who see the competition for tenants increase very slightly as new homes and offices are built. But the benefits are extremely visible to those who get to sell their TDRs, and to their allies. Of course, the competition for tenants helps the tenants too, but like landlords they are unlikely to notice.

None of this would surprise the late Mancur Olson, who explained how special interests normally find it much easier to organize to get special benefits, at the expense of the rest of the population. That is because each person in the latter only sees such tiny costs from each new crony scheme that it is not worth their time to oppose it. TDR schemes reverse that dynamic, by creating a strong coalition in support of beneficial reform.

In contrast, Mayor Bloomberg’s earlier attempted upzoning of NYC’s East Midtown failed due to political opposition. Professors Rick Hills and David Schleicher explain: “Although Mayor Bloomberg repeatedly emphasized the city would use [funds contributed by developers] to build parks and improve transit, he did not make clear who exactly stood to gain. No one knew exactly which new buildings would generate specific benefits for which interest groups. In effect, Bloomberg announced a meal of specific nutritious but unloved vegetables while keeping the dessert menu vague and hidden from view.” (My emphasis.)

Of course, Manhattan still has a housing shortage. TDRs aren’t perfect, and other ideas have had success. I will cover them in future.

2. Retirement in the US

Historically, most people worked almost until they dropped. There were no formal retirement plans. Old age was rife with poverty, insecurity, and distress. Wealthier countries have advanced a lot since then. The twentieth century saw many new retirement plans promising a fixed, regular payment in retirement. Often that payment increased with inflation. Such a ‘defined benefit plan’ or ‘DB plan’ is perfect for an individual retiree, because it gives them security and lets them plan their lives. In an ideal world, we would all have them.

But predictions are hard, especially many decades in advance. We cannot know how much general standards of living will rise, how large the working population will be, or even how long we will all live. If the wilder futurists are right that the average person today could live to a thousand, then every private defined benefit plan in the world is bust, and even public plans will face massive problems.

So some argue that in a well-run world, people saving for retirement should understand and bear at least some of that uncertainty. Encouraging the population to save more may mean more investment in infrastructure and innovation, which will lead to higher welfare in the long run.

You may not think that individual accounts to let individuals save for retirement are a good replacement for DB plans, because of concerns about inequality. But it’s hard to say that the arguments for them are completely irrational.

For the first few years after the private retirement savings accounts known as 401(k) plans were introduced, they made up a tiny fraction of retirement plan provision. But they grew rapidly. Assets in 401(k) plans rose from a multiple of about 2% of US GDP in 1985 to nearly 18% in 1998.

The legislative language that became section 401(k) of the tax code was ostensibly intended to clarify the tax status of a limited number of existing employer-funded plans, known as CODAs. It flew completely below the radar of public debate. According to the 1978 House and Senate committee reports, they thought they were merely restoring the ability to create new CODAs. The Joint Tax Committee thought the provision would have ‘a negligible effect on budget receipts.’

The real significance of 401(k)s only emerged in 1981 when the US Internal Revenue Service ruled that the provision covered plans where workers put aside their own wages. Suddenly the boom was on.

Private retirement plans have since come to tower over older plans. Contributions to 401(k) plans exceeded contributions to all other types of pension plans combined as early as 1994, and they continued to grow. According to Yale University’s Professor Jacob Hacker, this was ‘one of the most important developments in the history of US pension policy’. And yet it emerged with almost no public debate or controversy.

401(k)s illustrate an important rule: sometimes the easiest way to get the change you want is without any fight at all.

3. The National Health Service

Britain’s National Health Service was introduced to ensure universal healthcare. Although the UK had among the highest life expectancies in the world, until 1948 it relied on a patchwork of private medical provision that left many of the poorest without cover.

The NHS owes its creation to a charismatic Welsh former miner called Nye Bevan, the Minister of Health, pictured above. He was determined to create a state-run health service for everyone, free at the point of use, absorbing and replacing that patchwork.

He faced strong opposition.

Some healthcare was provided through friendly societies, whose local collectivist tradition contrasted with Bevan’s top-down, state-run vision. There were other private insurance schemes and services with their own misgivings. But Bevan’s strongest opponents were the doctors themselves.

The general practitioners or ‘GPs’ – which in the US today might be primary care providers, family practitioners or internists – had private medical practices. This was anathema to Bevan’s socialist heart. He wanted to stop practices being bought and sold; instead, he would transfer GPs to direct employment by the state. The specialists were also resistant to his ideas to nationalize their services.

Bevan initially adopted a strategy to divide and conquer. To win over the specialists, represented by the medical colleges, he agreed that teaching hospitals would have their own boards of governors; that nationalized hospitals could also treat patients who were paying privately; and that regional health authorities would have medical representation. He also made concessions on pay.

The British Medical Association, representing the GPs, opposed the NHS Act from the start. It feared that it would turn all healthcare into a local government service and damage personal freedom.

So Bevan made concessions to them too. Instead of becoming salaried government employees, general practitioners would contract with local Executive Committees. They would not be forced to move into the new local government-managed health facilities. And they would be paid per patient. Bevan even abandoned his plan to stop the sale of GP practices and to control creation of new ones.

In the end, Bevan won over enough of the opposition, and the NHS was created on 5th July 1948. Of course, the scheme had the same optimism bias of grand projects everywhere. The 1945 estimate of annual cost was £170 million; the actual cost for 1949 was £305 million.

In Bevan’s most famous line, he won over the doctors because he ‘stuffed their mouths with gold’. If the world is working inefficiently, economists readily agree that buying out the opposition to reform is often a good way to win. Where we know there are big inefficiencies, reforms to make almost everyone better off from the change may be possible.

Is Britain’s National Health Service perfect? Of course not. Many other countries ensure universal healthcare without resorting to a monolithic and inflexible system with months-long waiting lists for basic operations. Endless tales from doctors and nurses suggest that the NHS could be run better and more efficiently. Cross-country studies suggest that, on the same budget, it could do more for patients’ health. Increasing numbers of people instead choose private healthcare.

But Bevan reached his goal of offering healthcare for everyone, free at the point of use. He did so by understanding that the world is not zero-sum. Win-win answers are possible. He won by being realistic about the opposition, and clever and pragmatic enough to adapt his proposal until he won over enough potential opponents to get it through. In that, he is a useful lesson for us all.

The Theater District and the creation of the NHS are both examples of successful coalition building. Reform often fails without it. Those coalitions were made possible through clever policy design or ‘policy bundling’ – making sure enough groups benefit to make a winning coalition possible. Future posts will show how we can do that, in a non-partisan way, in many more areas than you might think. We will look at more housing reforms, immigration, driving, parking, cycling, banking, childcare, and education. We will also look at how and why other reforms failed.

401(k)s show another technique, which some call ‘policy layering’: introducing an innocuous supplementary scheme, initially small, which proves so popular that over time it balloons in importance.

These are just a few of the techniques that we can learn to help to make the world better. There is no finished list of tools. I’m launching this newsletter to share what I and others have learned so far, and to invite you to join in improving and building on it.

Care to join us? Please subscribe to Ziggurat for free, and we can get started. Perhaps you have friends who might be interested – please let them know too.