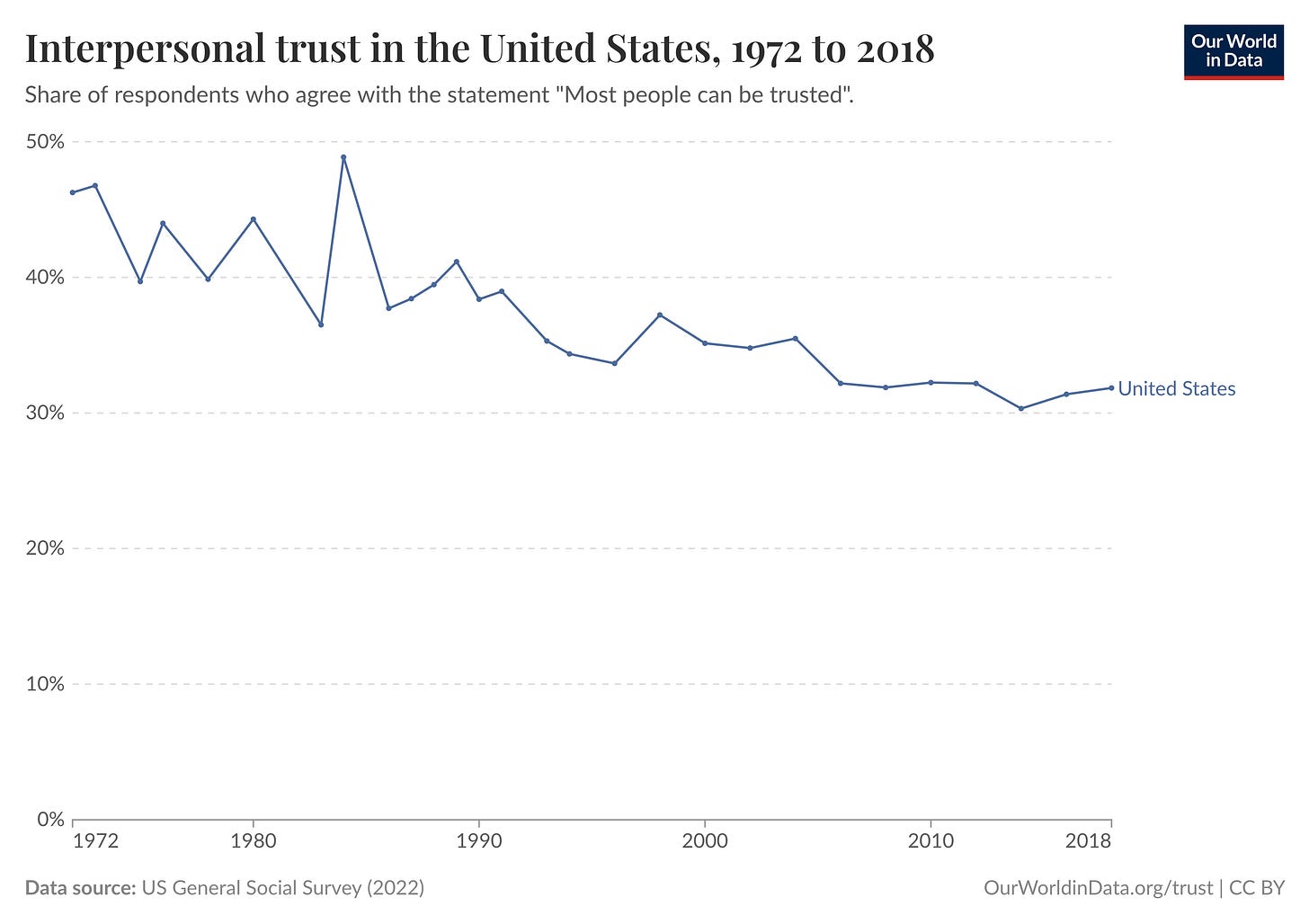

The US is experiencing a great decline in trust. According to the US General Social Survey, people who agreed with the statement "most people can be trusted" went from 49% to 25% between 1984 and 2022.[1]

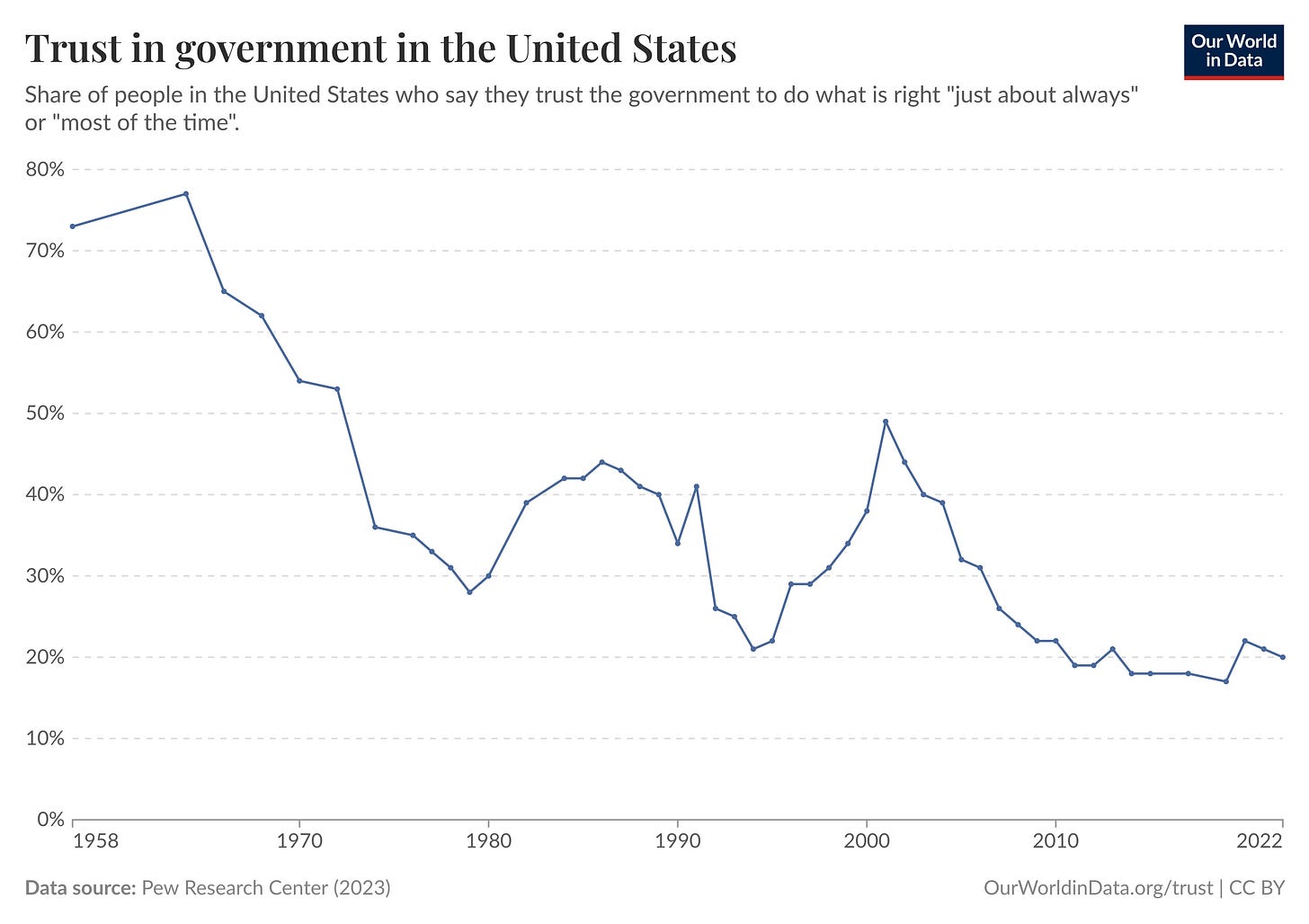

Trust in institutions is also falling. Over that same period trust in the government fell from 42% to 20%.

For civil services it fell from 56% to 41%, for the police it fell from 74% to 68%, and for congress it fell from 52% to a whopping 15%.[2]

Even international institutions, like the United Nations, are losing trust, going from 47% to 44%.

It’s not just institutions, organizations are also losing trust. According to the WVS, over that same period public trust in the press declined from 49% to 29%, trust in major companies declined from 49% to 31%, and trust in churches declined from 77% to 53%.

If we allow for shorter timelines we have data for other things that show a similar trend happening between 1998 and 2022. For political parties trust declined from 20% to 11%, for armed forces from 85% to 80%, and for the TV media from 24% to 22%.

The only things that seem to be gaining trust in that same period are, surprisingly, the courts, going from 35% to 57%, and progressive movements: with labor unions going from 30% to 33%, the women’s movement going from 48% to 54%, the environmental protection movement going from 44% to 54%.

What can be done about it?

So major companies are losing trust, while labor unions, environmental movements and women’s movements are gaining trust, to the point that all three are now higher in trust than major companies. This gives us reason to suspect that transforming major companies/organizations into worker co-ops would increase trust, since worker co-ops are better for labor, for women, and for the environment.

I would personally argue that our current political economy is not exactly stellar for all three, but we all know that the last one is the classic example of an externality that’s causing the destruction of a common good (in this case, the climate). I hope this data shows that we’re in a similar situation with another common good: trust.

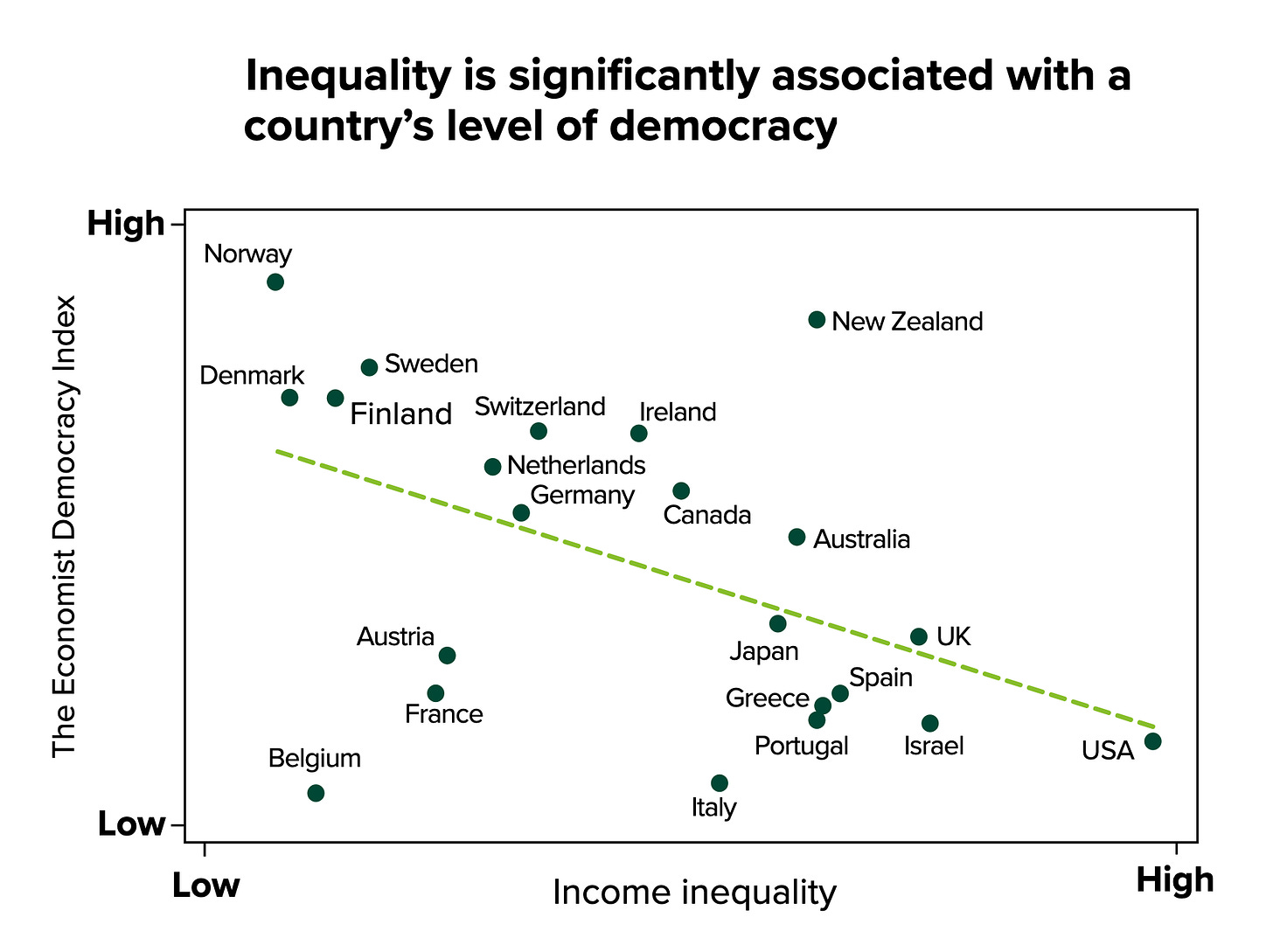

Unlike greenhouse gases, however, there’s no ready-made way to tackle this inside the current market. I mean, there are many strategies to increase social trust that can be employed outside of the market. I’ve previously talked about one such strategy: democratization. Getting rid of the two-party system is a no-brainer, but even beyond that, having non-deterministic elections creates a more proportional distribution of power, lowering minority resentment.

What if we try to deploy similar strategies inside the market? Is there a way to make the market itself more democratic?

Market democratization

One way to make the market more democratic is to implement more leftist policies. Giving the democratic government more teeth to regulate the economy obviously increases how democratic the market is, but other ideas like sovereign wealth funds, and strong labor unions do the same thing. Again, labor unions were one of the few things that had an increase in trust, so building on that, what other methods do we have to empower labor?

Worker co-ops are one of the oldest socialist ideas.[3] It’s conceptually very simple: the transition the enlightenment proposed for going from hierarchical systems to egalitarian systems, gets extended to the workplace.

It used to be that we had a two-tiered citizenry: one class owned and controlled the nation’s government (the nobility) and one class merely worked for said nation (the laborers). Then we decided that the laborers should also partially own and control the government. However, this practice was not extended to the workplace, which remains in that classic hierarchy to this day; with one class owning and controlling the firm, while the other class merely works for it.[4]

With this in mind the idea of a co-op becomes kinda natural. Instead of having owners who decide who manages the workers, the workers become part owners and get a say in how the firm is run. Just like the previous time we democratized a two-tiered system, this creates a boatload of positive effects for the political economy as a whole. So many, in fact, that I will have to spin it off into one or more future blogposts (to keep the scale manageable) and only focus on the effect on social trust in this post.

Trust and economic growth

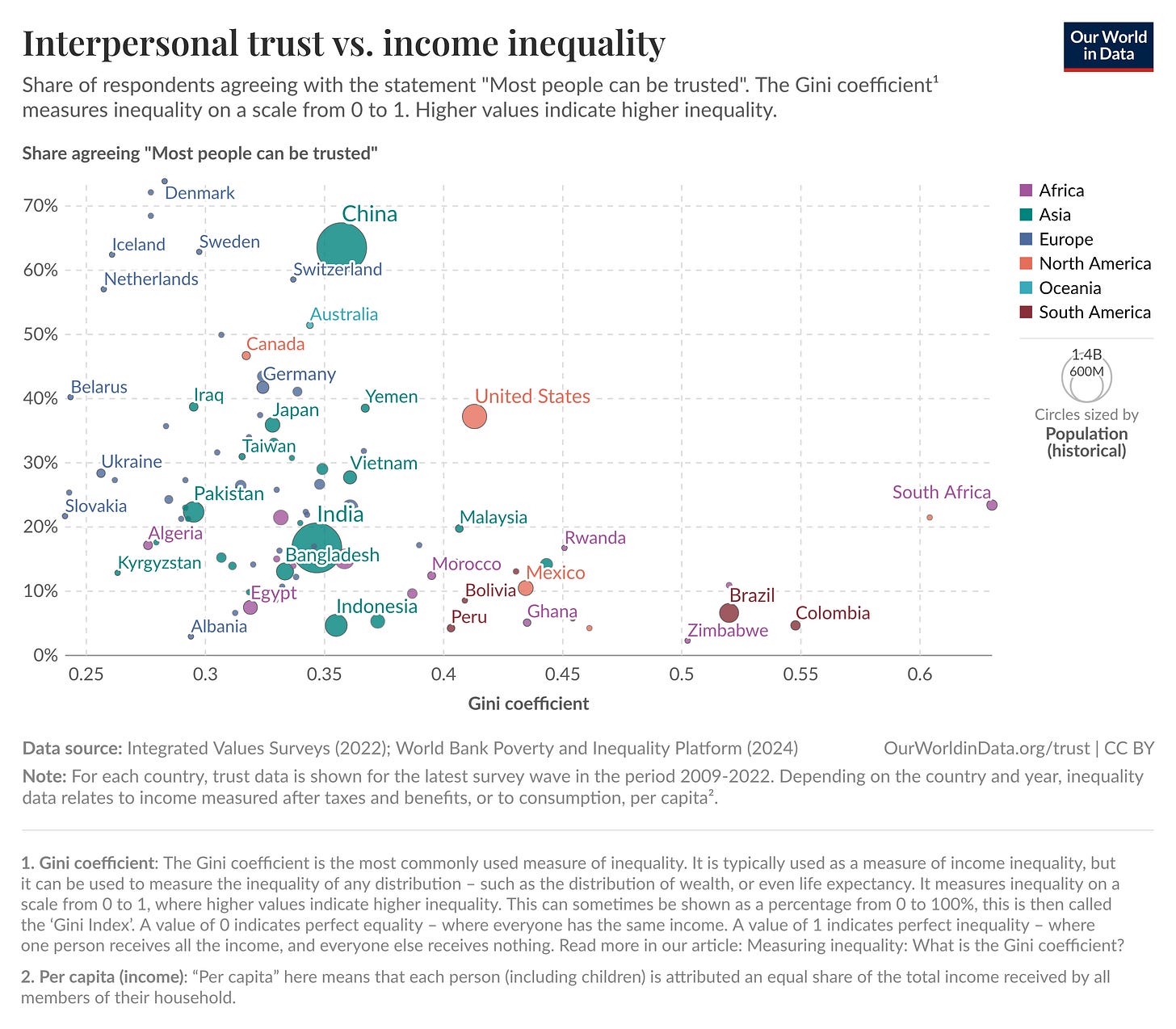

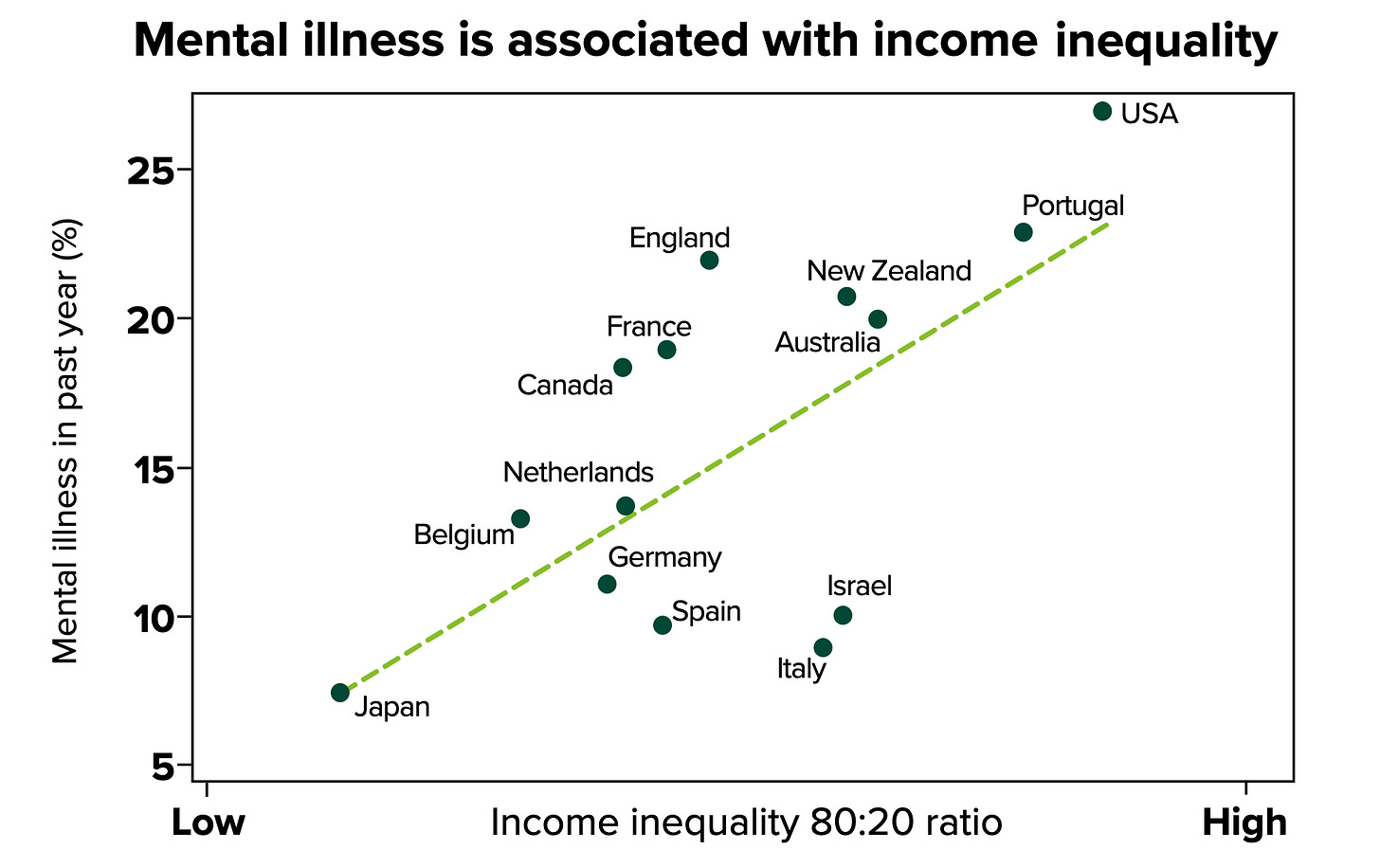

One of the biggest predictors for lack of trust is economic inequality.[5] This isn’t just ideological: it’s backed by data. Across countries, higher levels of inequality consistently go hand-in-hand with lower levels of trust.

The chart below is a handy visualization of this trend: more unequal countries tend to have significantly less interpersonal trust.

It feels almost superfluous to say, but research does show that people are more likely to trust others when they feel like they’re on the same level, not when they live in totally different economic realities.

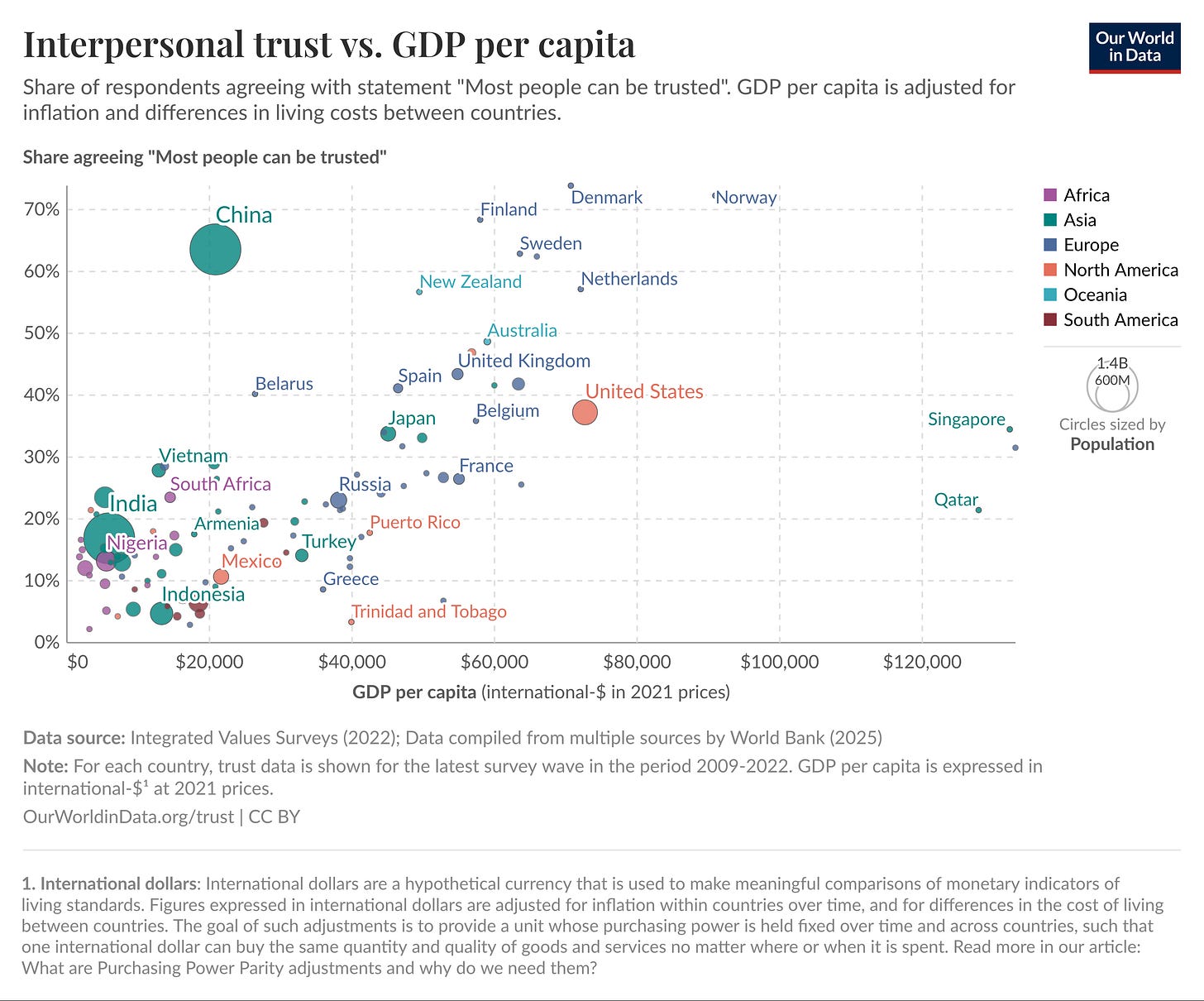

This is unfortunate because low trust screws with the economy. If you don’t trust the people you’re dealing with, you’ll hesitate to invest, to buy, or to commit. The less trust there is, the more everything slows down or gets bogged down in red tape:

This graph shows how strongly trust correlates with economic output. Countries with higher levels of social trust also tend to have higher GDP per capita. And this isn’t just a correlation, several studies show a causal link: trust drives growth. If people trust that others will follow through, that institutions will work, that cooperation isn’t a scam, they’re way more likely to invest in public goods, infrastructure, and long-term economic activity.

Low trust, on the other hand, raises transaction costs, undermines collective action, and makes people evade taxes because they don’t believe the system will use their money wisely. Trust is a public good: when it breaks down, everyone loses, even economically.

Trust and inequality

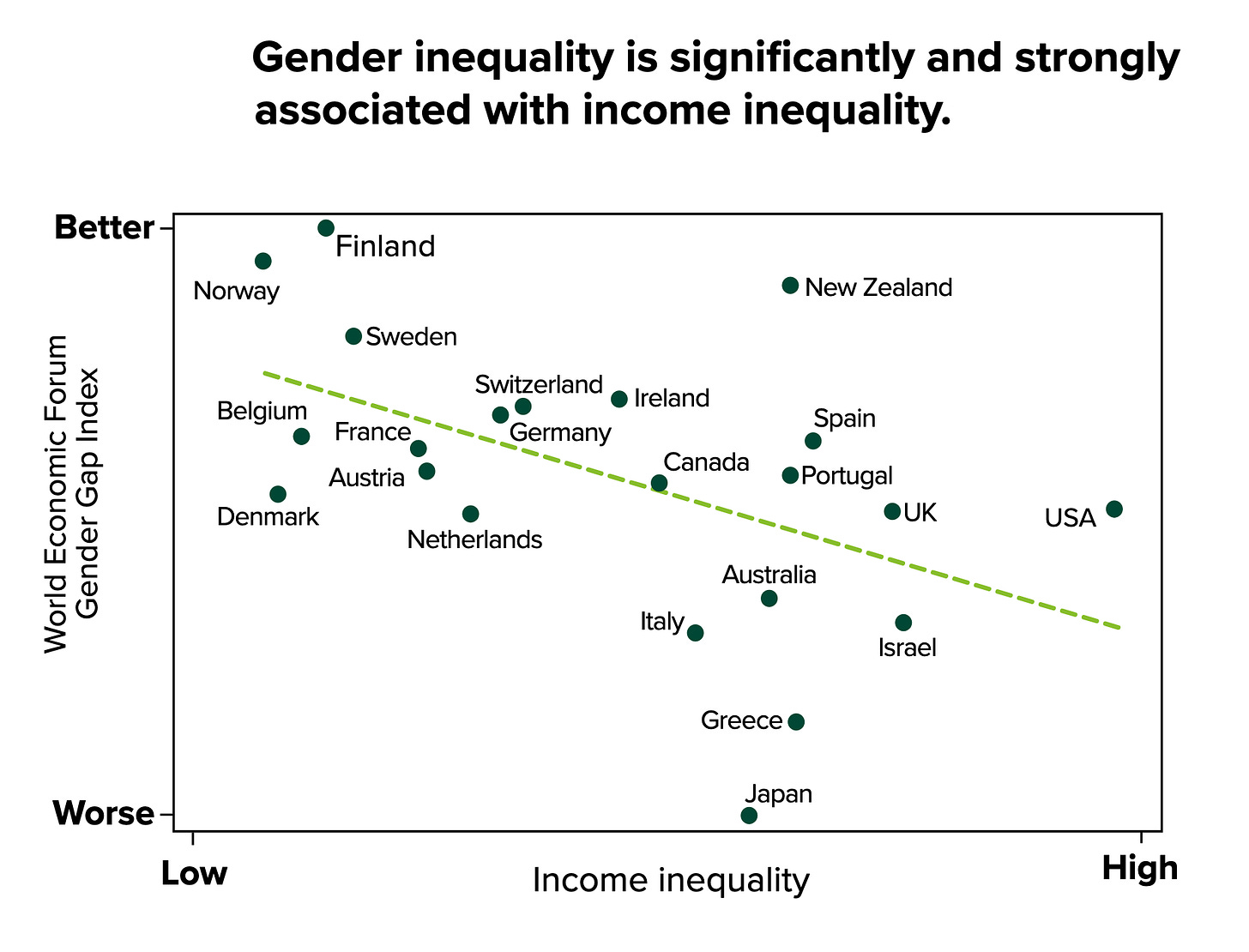

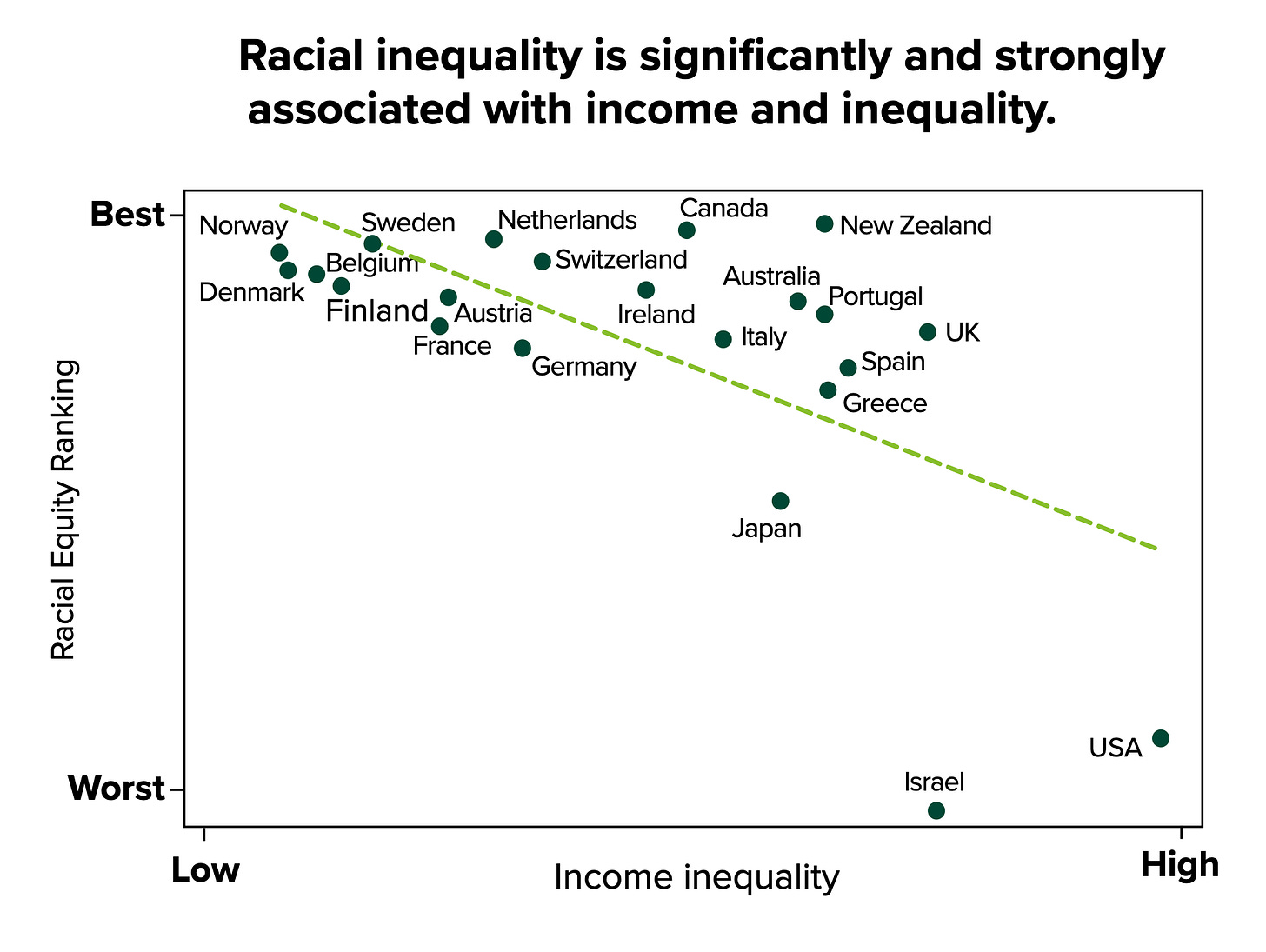

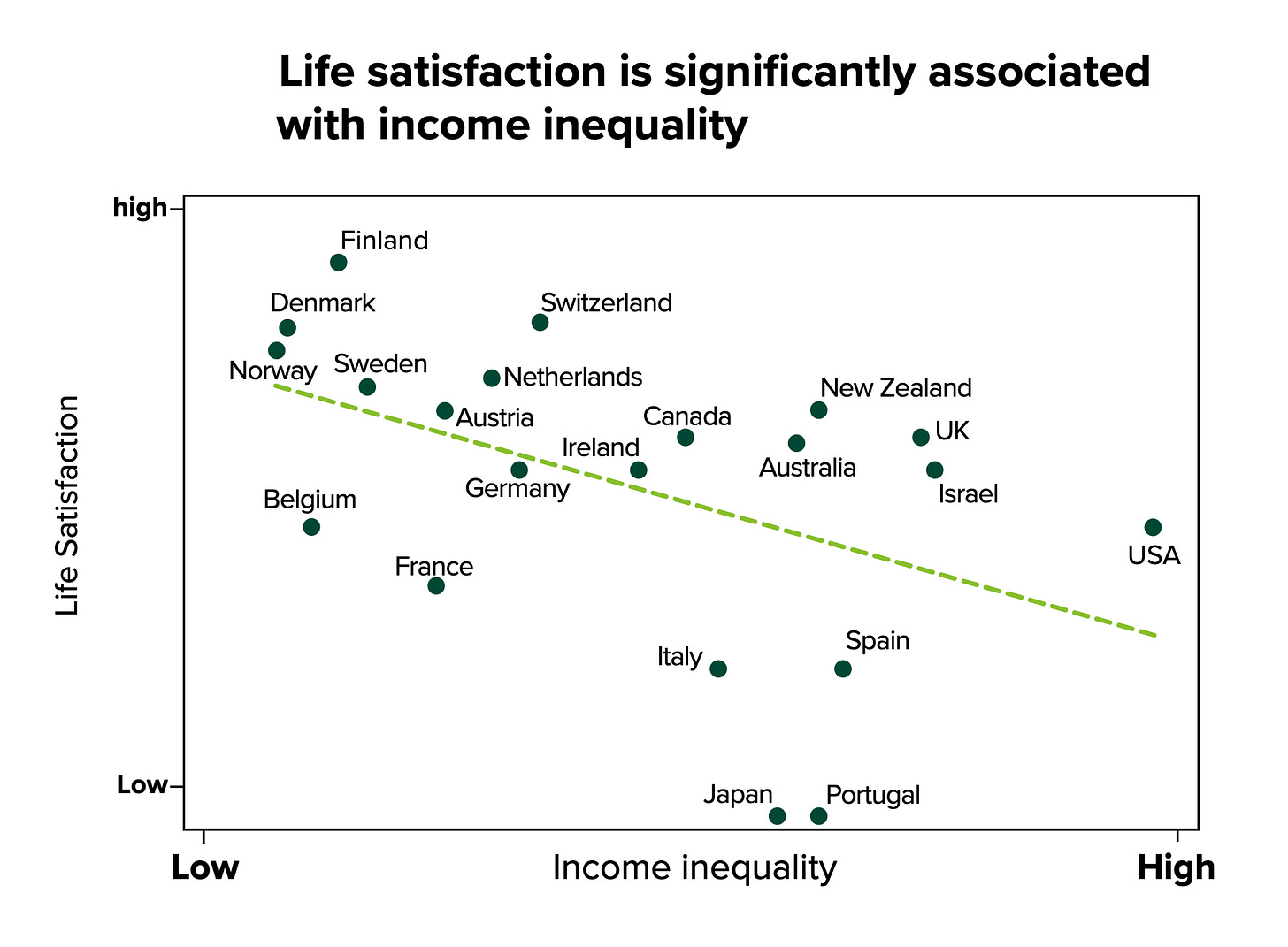

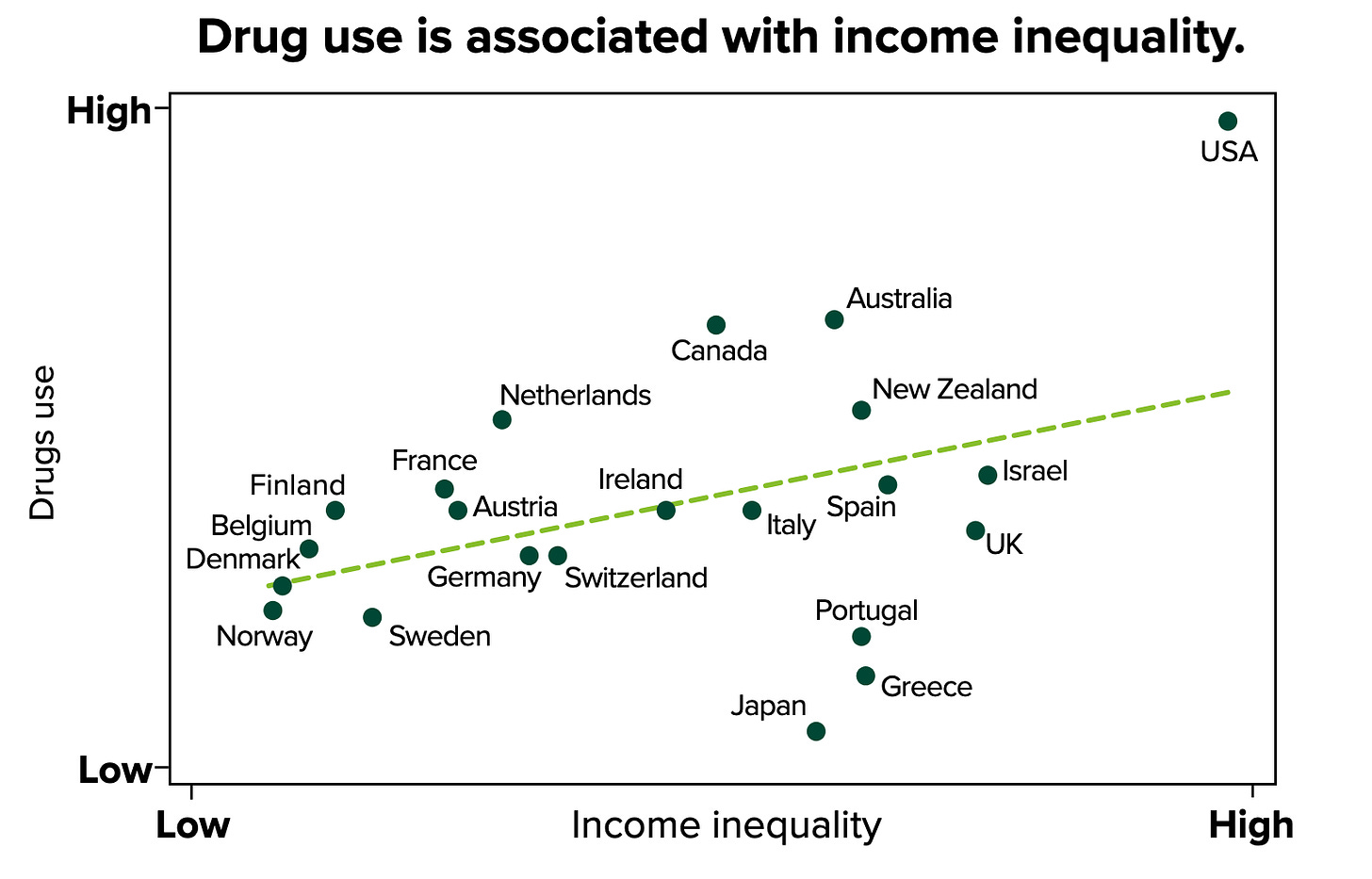

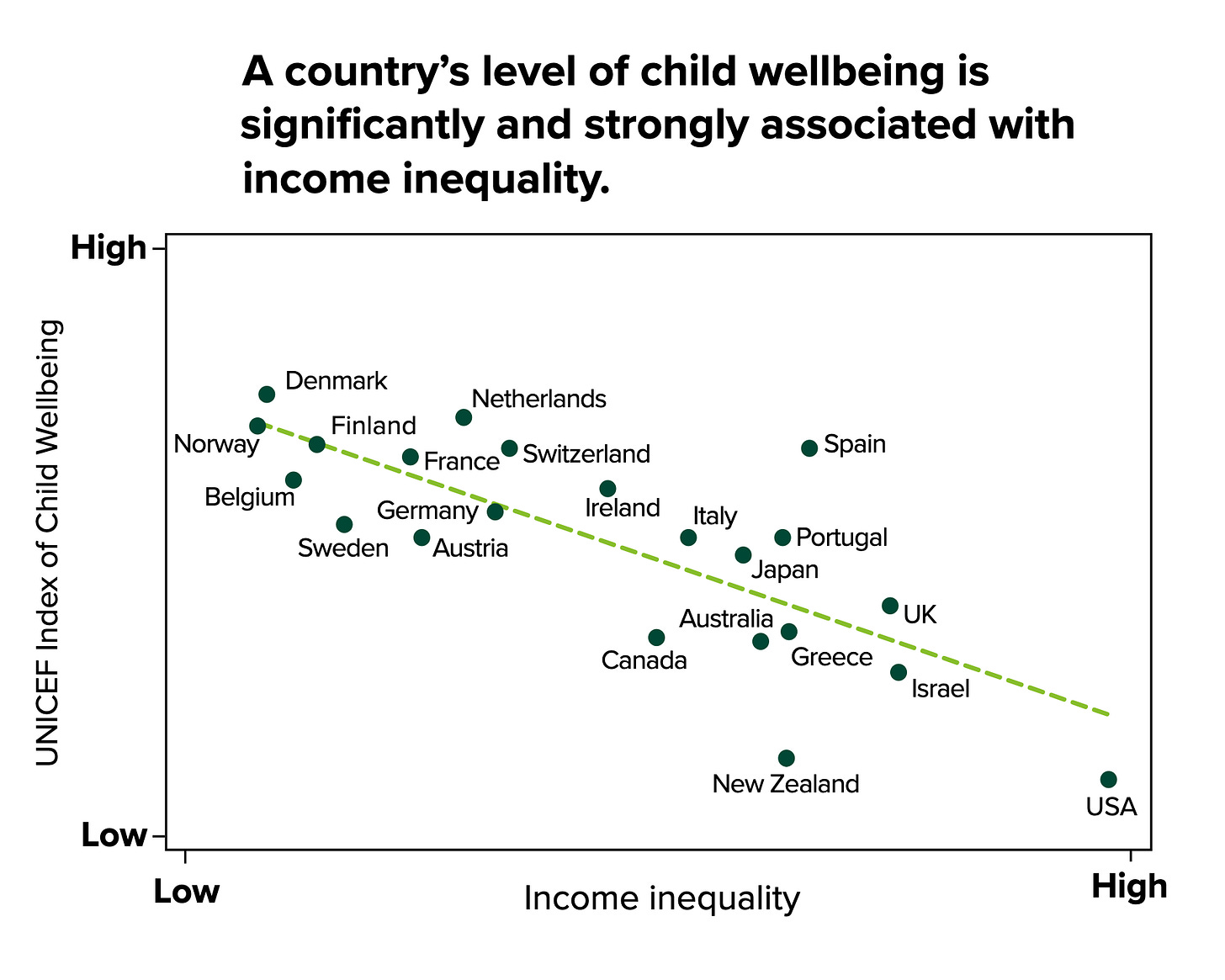

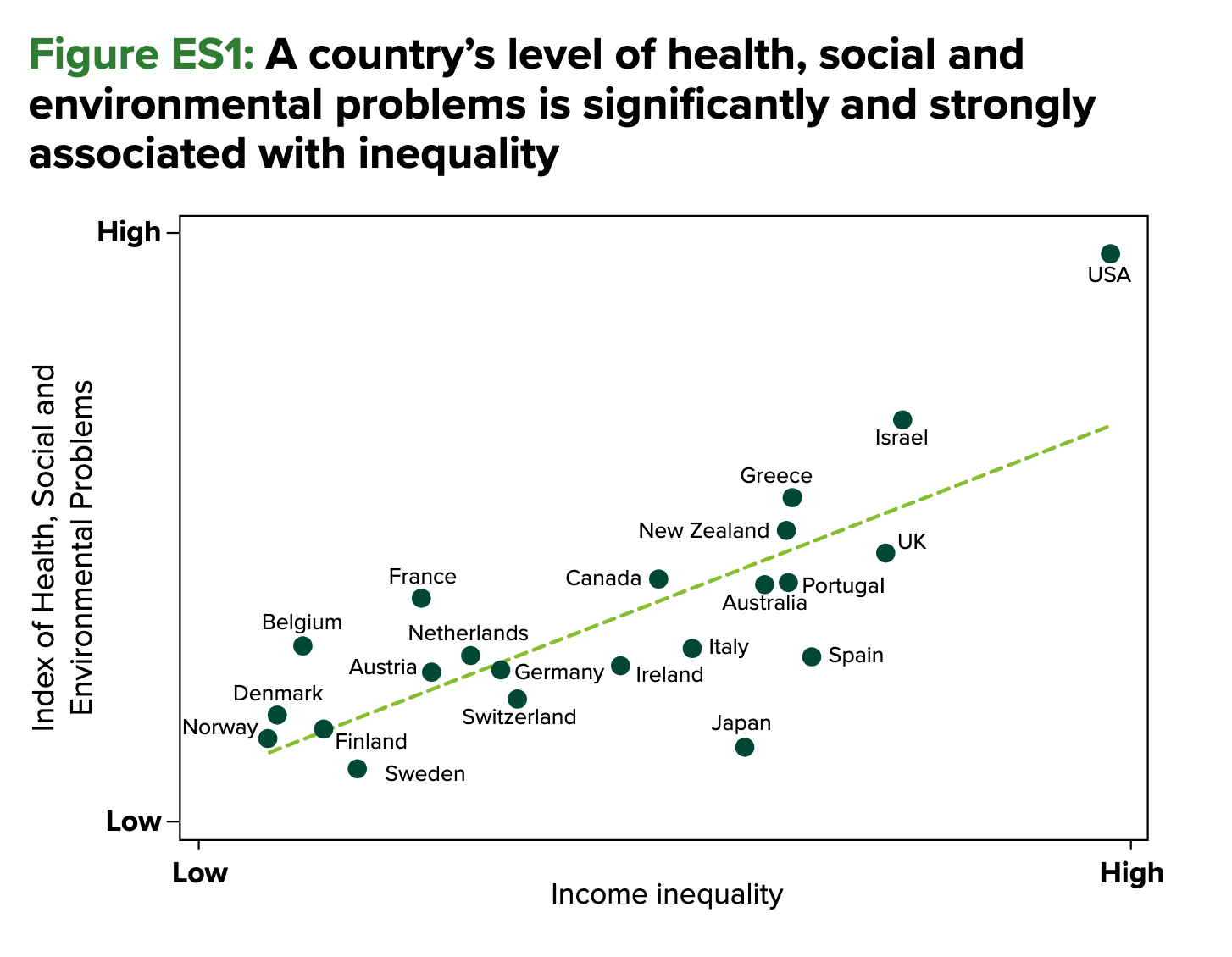

Now that we’ve looked at the link between trust and inequality, we can look at the consequences beyond just economics. This report from “Equality Trust” finds lots of links between inequality and social ills. It can lead to more inequality between different demographics within a society:

Decline in democracy and economic inequality seem to go hand in hand:

This all can’t be great for the average citizen:

For the record, socialists do not believe that worker co-ops are the uttermost optimal way to combat inequality. However, they are a way to combat it. Studies do show that worker co-ops have lower inequality within firms, which makes sense, if you can vote on how the wages are distributed you can vote against the CEO taking hundreds of times more than the average employee.

Capitalists argue that this comes at the cost of having lower average wages overall, and point to studies like this.

However, socialists counter that co-ops actually generate higher average income and point to studies like these.

So what’s going on here? Well, notice that these two claims don’t actually contradict. During economic downturns co-ops prefer to lower wages instead of firing people, which means that economic downturns cause the average wages to be lower, but the average income to be higher (since the unemployed earn nothing). While lowered wages suck, it’s still much more preferable to being fired. This is not only good for the workers but also good for the government, since it requires less investment in social safety nets.

The capitalist may counter that not firing people is all well and good, but if the firm itself goes under you’ll generate more unemployed. However, research shows that worker co-ops tend to actually be more resilient than conventional capitalist firms.

So capitalist firms externalize the costs that come with economic downturns (putting it on society at large) while worker co-ops internalize them. More good news for workers and the government.

But while all of this is solid evidence it isn’t a direct measurement of social trust in worker co-ops. Do we have that?

Direct measurements of trust in worker co-ops

A key study by Sabatini et al investigated how cooperative enterprises in Italy influence social trust. Their findings suggest that, unlike any other type of enterprise, co-ops are uniquely capable of fostering social trust, primarily because they rely on less hierarchical governance structures and prioritize broader goals than pure profit maximization. They say that such models help reduce uncertainty, lower transaction costs, and foster an environment where investment in ideas, human capital, and physical capital becomes more feasible.

Meanwhile, Blasi et al examined the impact of employee ownership on company culture and found it correlates with higher trust, perceptions of fairness, better information sharing, and greater cooperation. Their data analysis revealed that forms of shared ownership often go hand in hand with “high-trust” supervision, employee participation in decisions, and lower turnover: all of which can reinforce a sense of collective commitment.

Similarly, Joshi (not Yoshi) et al. looked at two major cooperative leagues (Mondragon in Spain and La Lega in Italy) and concluded that co-ops fare better in markets where cooperative principles are already established. In such environments, workers tend to have higher satisfaction, stronger social cohesion, and a clearer sense of shared purpose.

Other studies have explored connections between autonomy, well-being, and trust in co-op settings. Coad et al, for example, found that increased workplace autonomy significantly affects job satisfaction and life satisfaction. Park et al concluded that worker co-ops in Seoul help moderate the adverse effects of high job demands, indicating that the more democratic the workplace, the stronger the sense of trust and commitment among employees.

Conclusion

With trust in steep decline, it’s clear we need to rethink how our economy and institutions are structured. The scientific literature suggests that worker co-ops aren’t just a feel-good idea, they’re a practical response to a very real problem.

I’m not saying they’re a silver bullet, and implementing them at scale isn’t trivial, but if we’re serious about restoring trust then democratizing the workplace deserves to be on the table.[6] Given the stakes here, the fact that trust is crucial for a stable society and economy, exploring models that place greater emphasis on cooperation and shared ownership may be one of the most pragmatic steps we can take.

Click here to go to my blog.

- ^

The World Values Survey is more optimistic, but the data from US GSS is better. Even still, the WVS notes a decline by 2%.

- ^

The WVS does the same survey in different countries so they can compare data. Since most countries don't have a congress but rather a parliament, the survey question used the term ‘parliament’.

- ^

In fact, that’s what Marx and the other early socialists were really focused on. They never endorsed a planned/command-economy, which is what much of the West now wrongly equates with socialism.

- ^

Given that democracies are higher trust societies, you can probably see where this is going…

- ^

Inequality has been rising for years. There are strong links between all sorts of negative effects and inequality, such as worse conditions for workers, worse gender equality, and worse environmental problems.

Now, it’s difficult to ascertain to what extend one causes the other, but since worker co-ops both decrease inequality, and are better for workers, gender equality, and the environment, it doesn’t really matter. Worker-coops are a way to tackle these issues in any case.

- ^

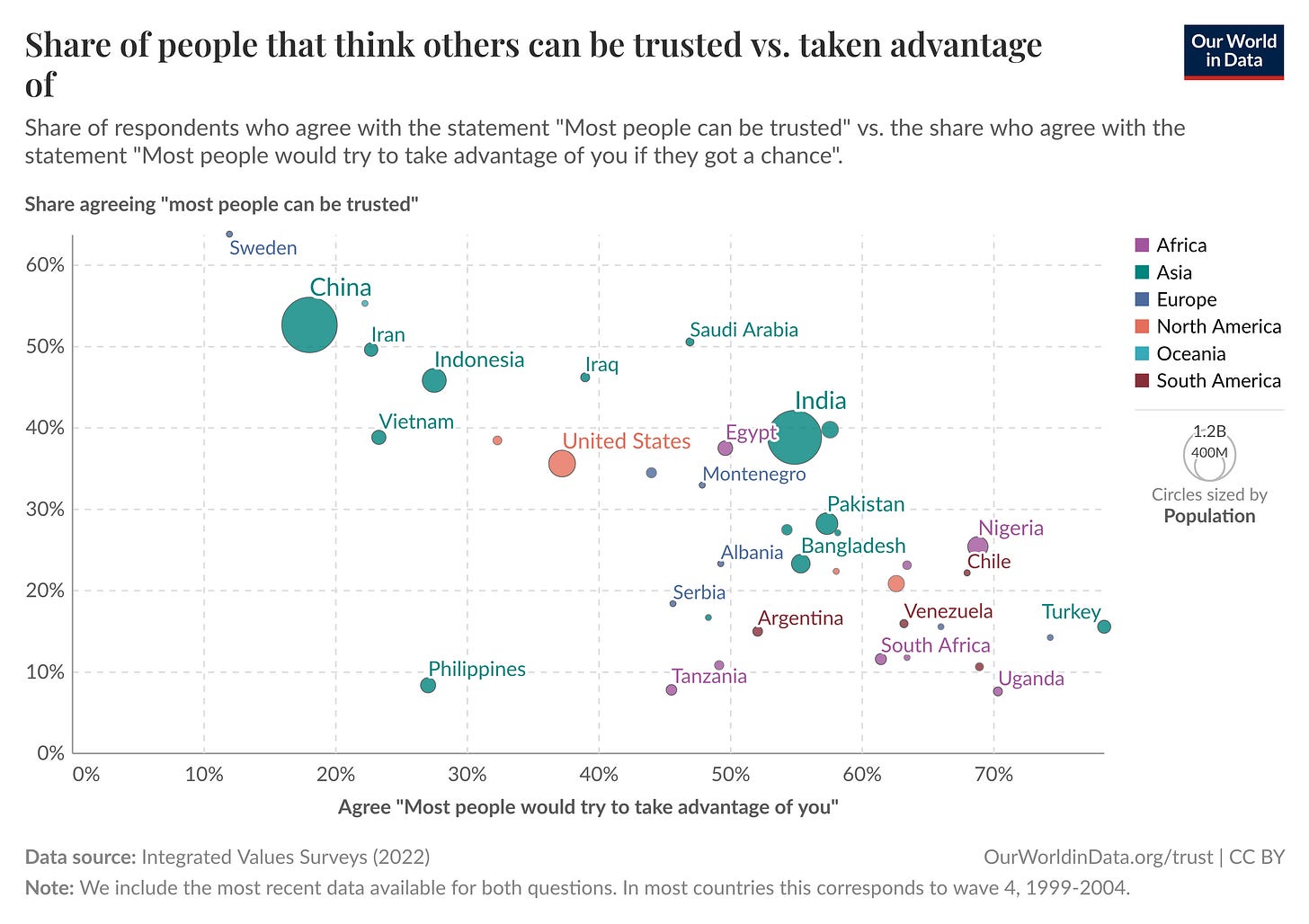

Originally this post also talked about mistrust, but then I realized that I didn’t have a source showing a decrease in trust corresponds with an increase in mistrust. Now most of you will probably say that this is basically tautological, but for the few skeptics among you, I did find a scatter plot:

To be on the safe side I only talked about a decrease in trust and not about an increased in mistrust, though they’re almost certain both happening in tandem.