Some thoughts on an influential movement which sought land redistribution in 19th century Ireland which has some lessons for building progress oriented groups today. A cross post from my new blog at https://robertsreflections.substack.com/

Starting Up

Without the help of the people our exertions would be as nothing - Charles Stewart Parnell (1885)

Of all the political questions that Ireland has confronted, one stands out: who should own the land? This was the subject of a nineteenth century political campaign known as the Land League. This organisation’s thirteen-year existence encapsulates the themes of ten millennia of property ownership: hubris, courage, deceit, ambition and, most importantly, imagination. Changes to Ireland’s land ownership system, driven in part by the Land League’s campaign, hold key insights for the country’s economic development, as well as political lessons for future movements.

In the late nineteenth century, the Irish economy was dominated by agriculture, and the majority of the population lived in the countryside. Millions of Irish farmers were tenants, and did not own the land they farmed. Though data is limited, in the aftermath of the Famine, only 28.4% of jobs were in industry, the rest were predominantly in agriculture, creating a society that disproportionately relied on the land. Rents were set by landlords, who could extract any surplus generated by their tenants. This meant that even if there was a good harvest, a farmer’s gains could be wiped out by rent increases. In this context, farmers struggled to build up any savings, which could have been used to invest either in the farm or perhaps in the education of children. As a result, Ireland’s agricultural labour productivity was half that of England’s. In addition, tenants could be evicted on a whim, creating an omnipresent uncertainty in the lives of the majority of Ireland’s population.

Worst of all, tenants were most likely to be evicted when food prices were lowest: in 1877 an agricultural depression enveloped Connaught causing a doubling in evictions from 1878 to 1879 as landlords attempted to secure higher rents to compensate for falling revenue from turnover from their personal estates. For these reasons, intellectuals like John Stuart Mill argued stridently against Ireland’s form of land ownership, going so far as to say rents must ‘ought never to be arbitrary’, i.e. not at the landlord’s discretion. From a country-wide perspective, economic development was extremely difficult in this equilibrium as most rental income was syphoned out of Ireland and into the absentee landlord class in the United Kingdom. From the perspective of individual farmers and their families, grinding poverty was a daily reality. Radical land redistribution had a precedent in the sixteenth century, when Henry VIII offered Gaelic lords the regrant of their land if they would first surrender it, and their loyalty, to him. These were later followed by land confiscations in the 17th century where more than 3 million acres of land were forcibly transferred from Gaelic clans to Anglo-Irish Lords, as well as Protestant settlers from Britain.

Since those 17th century land transfers, but particularly earlier in the 19th century, there had been intermittent campaigns for land redistribution. The Rockites were one such violent group in the south-west from 1821-1824. Named after a Robin Hood-esque folk hero, Captain Rock, the Rockites attacked landlords and land agents who attempted to increase rents, following warning letters signed by ‘Captain Rock’. However, most landlords were absentees – not even in Ireland – and the campaign lacked a figurehead, eventually running out of steam without lowering rents. Later, the Tenants Rights League believed the Famine, which resulted in the death of one million people and emigration of another million in the 1840s, had been enabled by unequal land ownership. The sudden depopulation created by the Famine created a unique opportunity for land consolidation and radical land reform. However their campaign was unsuccessful with the Tenants Rights League’s overt anti-capitalist messaging failing to capture the nation’s imagination.

The Installation of Captain Rock, Daniel Maclise

Most of Ireland experienced sufficiently poor harvests in the late 1870s that by the end of the decade, there were fears that the country was at risk of famine (within living memory of many people). Landlords continued to charge high rents despite tenants’ fears, particularly in poor counties such as Mayo. This distress provided a crucial opportunity for a new land reform-focused organisation. Land reform is a tightrope act. Many countries’ land was and is distributed in such an inequitable way as to be massively inefficient, and allow landowners to extract monopoly rents. But forcefully breaking up landholdings can border on the authoritarian. The question is how to break up landholdings in such a way that doesn’t also lead to a complete erosion of trust in the government, and a flight of the most influential and important landowners and businesspeople.

The Land League was established in Castlebar, Mayo, on 21st October 1879 by Charles Stewart Parnell, Andrew Kettle, Michael Davitt and Thomas Brennan, who met through the burgeoning Irish nationalist movement. The League sought the “three Fs” for Irish land: free sale, fixity of tenure and fair rent. Respectively, these meant a tenant could sell their holding to another tenant, a tenant could not be evicted if rent had been paid fully, and that courts would decide fair rent. Parnell et al believed that coordinated actions by a motivated tenant class could deliver this substantive change in land rights. The Land League differed from the Tenants Rights League by having an Anglo-Irish aristocrat among their founders: Parnell. Counting a great-grandfather and grandfather with involvement in the American War of Independence as well as the War of 1812, in addition to a grandfather who opposed the Act of Union, Parnell married both dissident and establishment pedigrees. Kettle came from an educated Irish Catholic background having attended Clongowes Wood, one of the country’s oldest Catholic boarding schools, and so could appeal to the few upper class Catholics that existed. Davitt, by contrast, epitomised the ordinary Irish Catholic of the time, having been born into abject poverty in Mayo (his parents shared the same landlord as some of my great-great-great-grandparents). Davitt was forced to emigrate for a time to England, exposing him to the country’s anti-Irish sentiment and fuelling his belief the Irish would never receive fair treatment from the English without drastic action. On his return to Ireland, he had an ability to appeal to the working class that complemented the political know-how of Parnell and Kettle. Completing the quartet, Brennn was born in Meath but spent his formative years in Mayo. He first established the Land League of Mayo along with Davitt, a precursor to the national organisation. The diversity of the founding team – at least by the standards of 19th century Ireland – enabled them to appeal to a broad swathe of society.

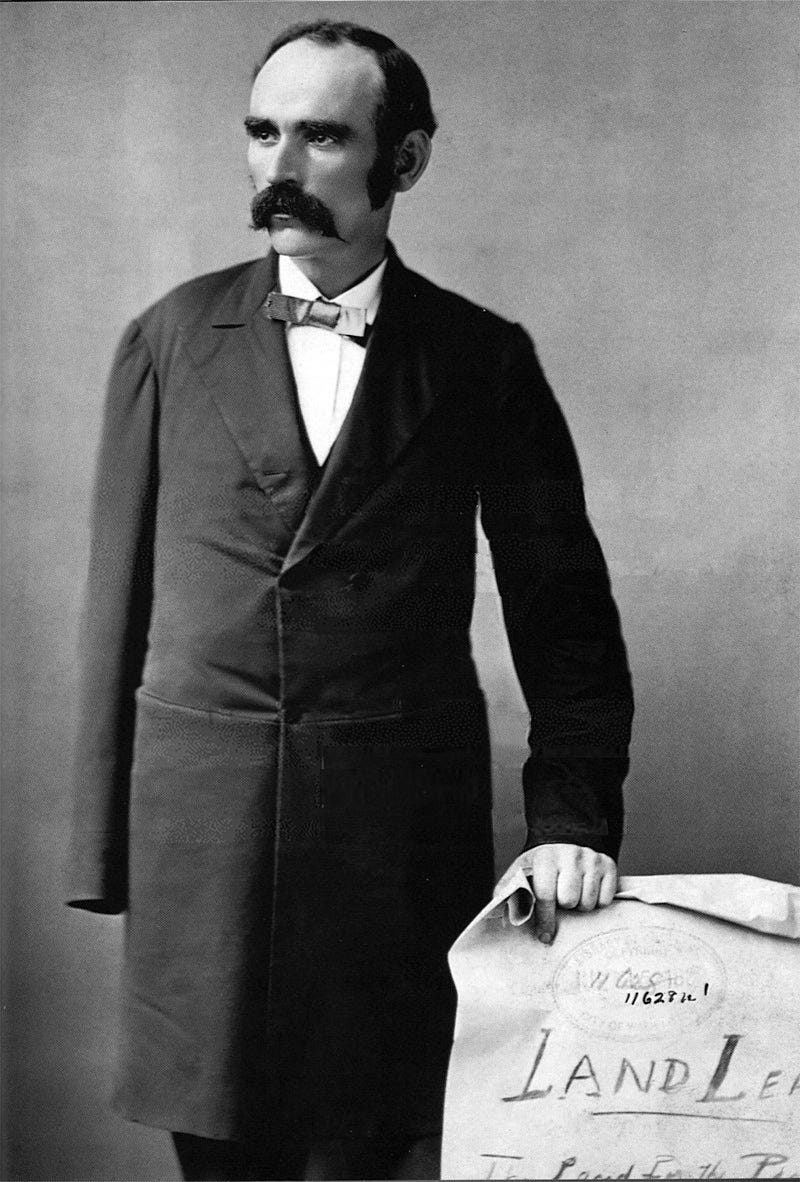

Michael Davitt, he lost his right hand in an industrial accident at the age of 11

The Land League was more combative than previous land reformers. By marketing their campaign as the Land War, they drew parallels with the 1798 Rebellion, which sought to gain greater legislative independence for Ireland. Though a failure, that rebellion proved a combination of motivated Anglo-Irish and Irish activists could manage to hold the British to account for a time. Wolfe Tone, the ringleader of the Rebellion, was a Protestant, as was Parnell. In a sectarian Ireland, the multi-denominational nature of the Land League gave it broad appeal, but often put it at loggerheads with both the Catholic and Anglican churches. The first shots of the Land War were fired when Davitt organised, in the words of a local newspaper, a ‘monster meeting’ in the tiny village of Irishtown, Mayo, with approximately 13,000 attendees. Arguing vociferously for rent reform, Davitt and other speakers said that only through unity could farmers effect change; coordinated action would force the hand of the landlord class to implement the Land League’s aims. Critically, the Land League created structures to mobilise women and children in their efforts.

No movement, no matter how popular, can last without money. For this reason, Parnell embarked on his first fundraising trip to America in 1880. This was the first of what has become a strong tradition of the Irish-American diaspora providing funding for Ireland’s most impactful campaigns, including the movement for independence in the 20th century and IRA bombing campaigns. Parnell’s fundraising efforts were so successful that a Land League of America was created. Fundraising hinged on presenting famine as an Irish problem caused by the English and the land ownership system they imposed on Ireland, as opposed to natural factors like the limited availability of land. Indeed, emigration was framed as a response to the inequalities created by the Protestant Ascendancy, and the Land League argued the tide could be turned if land reform occurred. In these ways, the Land League appealed to the Irish fearful of imminent starvation and the Irish diaspora’s immigrant experience.

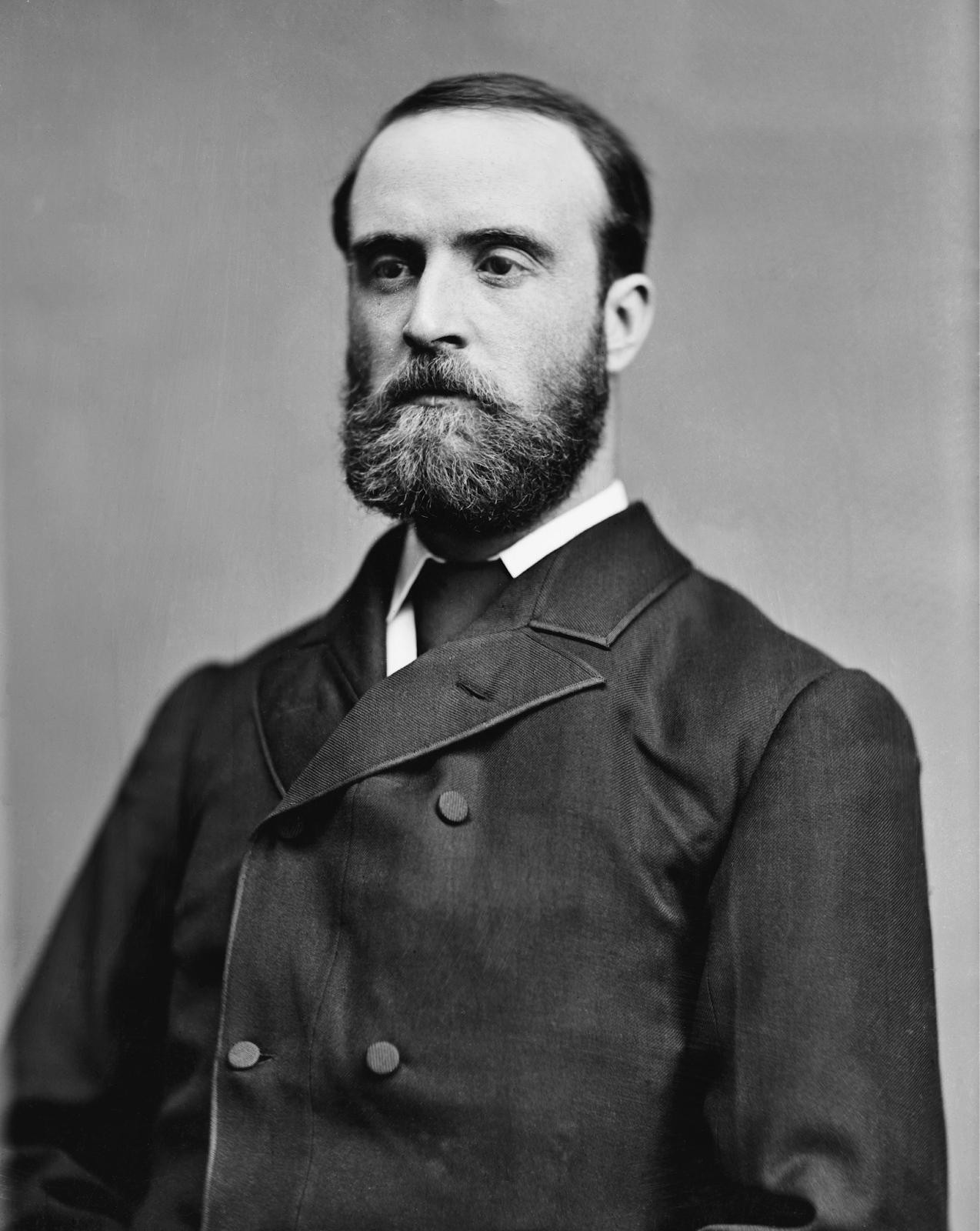

Charles Stuart Parnell

Brrrr

The assertion that landlordism is essential to the supremacy of English authority in Ireland, that it constitutes "the garrison" by which the country is held in subjection, is one of those popular English fallacies which only needs to be examined in order to be thoroughly exploded - Michael Davitt, A Statement for Honest and Thoughtful Men (1882)

Pioneering tactics were a key component of the Land League’s campaign. Captain Boycott was a land agent in Mayo responsible for collecting rents on behalf of absentee landlords. Land League activists convinced tenants under Boycott’s domain to cease working on the local landlords’ estates; the rest of the community were encouraged to treat Boycott as an outcast (this is the origin of the verb ‘to boycott’). Even Boycott’s servants stopped working for him. The moniker of an outcast was too much for Boycott prompting him to write a letter to the Times and in quick succession his circumstances became a matter of public interest across Britain and Ireland. The Boycott Relief Fund was established in Belfast to rescue the land agent stranded in the wilds of Mayo and, most importantly, to harvest the crops on his own land holding. The journey was a success though Boycott’s long-term safety was not guaranteed; he was eventually forced to leave Ireland for England escorted by members of a cavalry regiment. The success of this tactic meant boycotting spread across all branches of the Land League. If a person took over a farm from which a Land League member was evicted, the new tenant would be boycotted. This involved the new tenant’s name being published in papers, and plastered on walls and trees with all notices being signed ‘by the order of Captain Moonlight’.

Recognising that improving tenancy rights in Protestant Ascendancy Ireland was a moonshot idea, the founders pioneered various strategies. Parnell hired his sister, Anna, to lead the Ladies’ Land League to push for change using ‘a thousand ingenious feminine devices’. A Childrens’ Land League was created where Ireland’s future was fed a literary diet of sufficiently nationalist literature and partook in various games to improve their coordination skills. Davitt was the Agrarian revolutionary that managed daily operations, and Parnell was the statesman that successfully contested elections on the group’s behalf. At the centre of the attack was the ‘The Nation’, a nationalist newspaper that allowed members of the movement to contribute to the discussion in the public square, which following a merger and rebrand in 1900 began the path to becoming today’s Irish Independent.

It may not have been official Land League policy, but members did not shy away from violence; 76 murders were connected to the organisation. The victims were landlords and land agents. The most effective assassinations were those of Lord Cavendish, the Chief Secretary of Ireland, and Thomas Henry Burke, Ireland’s most senior civil servant. Cavendish was married to the niece of the Prime Minister at the time and had only arrived in Ireland the previous day. This guaranteed attention from the British establishment which enabled the more radical elements of the Land League to be taken seriously. The mean number of murders in rural Ireland per year was 5 from 1852 to 1878, but from 1879 to 1882, it increased to 17 per year. Indeed, the mean murder rate did not fall to pre-Land League levels until 1883.

The Cavendish and Burke murders were claimed by the Irish National Invincibles, whose members were connected to more radical elements of the Land League. These murders were later mirrored by the ‘Apostles’ during the Irish War of Independence – twelve men led by Michael Collins who killed fourteen British Secret Service agents. The Land League was therefore fundamental to later political movements in Ireland by developing targeted political violence as a means of asymmetric warfare. Other tactics included using district courts to delay evictions, and ensuring evicted tenants would not be replaced by new ones. International funding was critical to enabling this; donations from abroad paid for legal fees and related expenses.

The Land League’s campaign proved successful given that the Land Law (Ireland) Act (1881) instituted the three Fs. The Land Law Act also created the Land Commission, which examined land ownership with a view to creating a more equitable property system. To finance land purchases, the Ashbourne Act (1885) provided £5m to tenants, a sum that was doubled in 1888. To further expand the route to property ownership, the Purchase of Land (Ireland) Act 1891, the Balfour Act, introduced land bonds as an alternative method of property financing. In the three years following this act, 14,002 applications for land purchase support were registered - half of these were from Ulster. It appears the land redistribution policy enacted was almost universally successful among elite landowners except for in the province of Connaught where there was a much greater ambivalence towards centralised authority. In the case of land bonds, the annual coupon was 4-5% paid over 33-45 years under various guises of the legislation governing the financing of land purchases. The Land League had achieved its policy aims, but did not drastically improve the living standards of farmers. This stands in contrast to east Asian land reform, which created incentives that directly rewarded hard work and innovation. Once farms were reorganised around small individual freeholders, yields increased, which in turn led to higher rates of saving and investment. This surplus also allowed farmers to become consumers in their own right, creating demand for consumer goods produced in urban areas. Japan, South Korea and Taiwan all successfully implemented land reform, giving them the resources they needed to make a push into manufacturing, and their economies boomed afterwards.

Notably, these Asian countries pursued land reform as independent states, not as colonies as in Ireland’s case. Colonies typically have some form of rentier relationship between the ruler and the ruled, so perhaps Ireland could never have realised the full extent of the benefits of increased land ownership whilst it remained a colony. On the other hand, the industrial success of Belfast – under the same constitutional arrangement as the rest of Ireland until 1920 – implies that economic development was possible even in a colonial situation. These questions of comparative economic performance remain under-discussed on both sides of the Irish border. Furthermore, the Land League’s immediate achievements appear to be less effective when the tapestry of Irish land reform in the 1920s is considered. The Land Commission forced Anglo-Irish aristocrats to sell their estates to the state, which were then subdivided and sold back to former tenants. In this case, the process of land reform totally ignored the desires of the former ruling class and instituted a large-scale attempt at democratising land ownership, virtually destroying the power of the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy overnight. It is unlikely such an aggressive move would have occurred without the Land League or some such group, but the League was unable to achieve its true objectives without wholesale constitutional change.

Despite questionable economic results, the Land League offers several lessons for successful movement building in Ireland: the importance of appealing to a number of demographics, including various classes and religions; a charismatic, highly motivated core leadership team; consistent funding; and persistence.These characteristics are observable in similarly successful movements in Ireland. The 1916 Rising leaders had a leadership group that encompassed Irish complexities much like Land League did: Roger Casement served as a Parnell-esque figure, accompanied by the highly charismatic triumvirate of Padraig Pearse, Michael Collins and Eamon de Valera, all of whom were skilled orators. The Irish diaspora also played a pivotal and commensurate role in the Rising’s funding. The Rising’s surviving leaders went on to fight in the War of Independence and ensured the Nationalist movement continued to have these traits. In the end, independence was achieved for most of the island.

Similarly, unsuccessful Irish movements lack some or all of the Land League’s ingredients, such as the movement for Home Rule, which failed to appeal to the working class or ignite the popular imagination, and lacked orators of Parnell’s stature. Sinn Fein and the IRA have historically lacked support across religions at path-defining points in Irish history, and the same can be said for Unionism. Tactically, the Land League offers fewer lessons. Political violence has been employed extensively in Ireland in the 20th century, but no right-thinking modern movement would engage in it today. Strong communications in the form of a newspaper – and no doubt private letters – can be emulated today with social media and private messaging. Boycotts and court battles can slow or impede the state, but they aren’t good methods of forcing the state to be more effective, which is often a more pressing need today. Indeed, Irish government institutions have mostly failed to pursue ambitious policies since independence, with T.K. Whitaker and Noël Browne offering notable exceptions to this rule. Aspects of the Land League’s campaign could be worth replicating for those trying to solve Ireland’s biggest problems. There are numerous parallels between 19th century and 21st century property ownership, with the similarities becoming most striking after the demise of the Celtic Tiger.

Today, Ireland is a nation of tenants, much as it was in Davitt’s day. Given the success of the Land League, and its free market ideas, a movement that seeks to replicate its victories must be explicitly pro-market and value the potential of increasing individual agency as opposed to the socialism espoused by the Tenants Rights League. Every successful attempt to transform Irish society has been driven by misfits,those at the fringes, yet their ideas have ultimately won broad appeal in some way. The Land League’s influence has gone well beyond a single policy topic, stretching into the following century and across the longer arc of Irish history. If a progress-oriented movement is to be built in Ireland, such a group ought to base itself on the organisational framework created by the Land League.

Acknowledgements

This was initially pitched as an article for an Irish publication, the Fitzwilliam. Thanks to Fergus McCullough for seeking my thoughts on the Land League.

Writer’s Note

Henrik Karlsson spurned me into action through this blog post which Fergus sent me a number of months ago. I have now started posting my thoughts online as an experiment as I look for new projects and seek out interesting people that are working on ambitious things. Please feel free to contact me at tolanro [at] tcd [dot] ie.

Sources

Cormac O’Grada, Ireland Before and After the Famine: Explorations in Economic History, 1800-1925

Foster, R. F., Modern Ireland, 1600-1972, London, 1988

J.S. Mill, ‘Principles of Political Economy’ (1848)

Maginn, C. (2007). “Surrender and Regrant” in the Historiography of Sixteenth-Century Ireland. The Sixteenth Century Journal, 38(4), 955–974. https://doi.org/10.2307/20478623

Smith (1993). The Land-Tenure System in Ireland: A Fatal Regime

Comerford, R. V, 'The land war and the politics of distress, 1877–82', in W. E. Vaughan (ed.), A New History of Ireland, Volume VI: Ireland Under the Union, II: 1870-1921, New History of Ireland (Oxford, 2010; online edn, Oxford Academic, 22 Mar. 2012)

Curtis (1963). Coercion and Conciliation in Ireland

Butler, W. F. (1913). The Policy of Surrender and Regrant. I (Continued). The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 3(2), 99–128. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25517378

Jordan (1998). The Irish National League and the 'Unwritten Law': Rural Protest and Nation-Building in Ireland 1882-1890